Yancey Strickler, the Kickstarter founder, makes a passionate argument that we can, and must, redefine the measures of success if we want a stronger society than the one we have today.

He describes today’s business world as one of “crumbling infrastructure, the dominance of mega companies, and the rise of offshore tax havens.” He isn’t opposed to money, or even wealth. “If businesses were optimised for the community or sustainability” he says, “the rich would still be rich, just not as rich,” whilst the vast majority of people would be wealthier and happier.

In the global pandemic of 2020, the impact of a single-minded pursuit of profit was brought into sharp relief as the business world shut down and huge numbers of people lost jobs. The lack of healthcare provision and social safety nets plunged workers of all levels into turmoil. Similarly, hospitals lacked essential equipment because of a relentless drive for efficiency. As stock markets plunged, and trillions of dollars of value were wiped out, businesses started to realise the folly of their frugality and lack of compassion.

Business has sought to maximise financial performance for so long that it’s hard to imagine another reason for companies to exist.

Profitability and value creation.

Profits have become the predominant metric of success. Many people in business still think that market share and sales revenues are the goals, yet for some time we have seen that big is not always better. As customers and products have become less equal in their relative profitability, it is often more profitable to focus on less rather than more. Similarly, multiple channels with different efficiencies, and a drive to discounting, means that more sales don’t always convert into more profits.

The notion of “value” us important. Businesses are often defined as value exchanges, creating value for customers and capturing value for the business.

Economists evaluate businesses based on the sum of future profits, adjusted for how likely these profits are to emerge. Strong brands, relationships and innovation pipelines make future profits more certain. Their sum is known as the enterprise value, reflected externally on stock markets, based on the judgement of analysts and behaviours of investors, as market value. Executives are incentivised to deliver profits, however more thoughtful incentives will encourage their preference to sustain profits over time, often based around total shareholder return, the growth in market value plus a share of dividends.

Business leaders can decide how to design their value creation machine, in particular how to share value between all stakeholders over time.

As profits emerge each year, leaders decide how much to allocate to employees in salaries and bonuses or as improved conditions, how much to allocate to customers through innovative products and services or better prices, how much to allocate to investors in dividends or cash, and how much to share with society through social initiatives or more generally through taxation. The relative allocations, and for what, determine how effectively the business invests for its future, to sustain the creation of value – or in other words, to grow a larger “value pie”, from which everyone can enjoy a healthy share.

However, that ideology gets disrupted by greed, particularly by owners who are more interested in making a quick return, rather than seeing a sustainable long-term business.

James O’Toole is his book “The Enlightened Capitalists” explores the history of business leaders who have tried to combine the pursuit of profits with virtuous organisational practices – people like jeans maker Levi Strauss and the Body Shop’s Anita Roddick.

He tells the story of William Lever, the inventor of the Sunlight soap bar who created the most profitable company in Britain, the origins of today’s Unilever, and used his money to greatly improve the lives of his workers. In 1884 he bought 56 acres of land on the Wirral, near Liverpool, and built a new town for his workers, known as Port Sunlight, where workers and their families could live healthier and happier lives. Eventually, he lost control of the company to creditors who promptly terminated the enlightened practices he had initiated. The fate of many idealistic capitalists.

From shareholders to stakeholders

In recent years the relationship between business and society has become increasingly fractured. Whilst there is nothing wrong with shareholders, and nothing wrong with profits, the culture of capitalism seemed increasingly out of sync with the world. A series of economic, social and environmental crises made it all the more obvious.

Of course, most businesses have woken up to the importance of sustainable issues, and their responsibilities to society over recent years, but they have largely seen them as a new component of capitalism.

10 years ago, I wrote the book “People Planet Profit: How to embrace sustainability for innovation and growth” which sold many copies, but little seemed to change. Yes, we got the sustainability report as an appendix to the annual report, the foundation that operates at arms’ length from the core business, and a host of initiatives to reduce emissions and waste. At the same time, social enterprises emerged – indeed, I was a CEO of a $50 million non-profit business myself – but such organisations were still seen as a different breed from commercial businesses. Core business didn’t change.

And then three things happened.

- In January 2018, BlackRock’s Larry Fink wrote a letter to the CEOs of all the companies who he invests in, saying that he would not continue unless they could demonstrate that they will delivering on a significant “purpose before profit”. BlackRock is the world’s largest investment firm, a $6 trillion asset manager. This was seismic.

- In August 2019, The Business Roundtable, the most influential group of US business leaders said they would formally embrace stakeholder capitalism, built on “a broader, more complete view of corporate purpose, boards can focus on creating long-term value, better serving everyone – investors, employees, communities, suppliers and customers.”

- In January 2020, the World Economic Forum launched the Davos Manifesto for “a better kind of capitalism” saying “the purpose of a company is to engage all its stakeholders in shared and sustained value creation” with “a shared commitment to policies and decisions that strengthen the long-term prosperity of a company.”

Klaus Schwab, founder of WEF, called it “the funeral of shareholder capitalism”, but also as the bold and brave birth of stakeholder capitalism.

Marc Benioff of Salesforce added that “Capitalism as we know it is dead. This obsession with the pursuit of profits just for shareholders does not work”. IBM’s Gina Rometty said that there are now two types of business “good and bad”.

Jim Snabe of Maersk said, “companies need to start making the change right now, to the way they work, the resources they use, the taxes they pay, and the decisions they make.”

Smarter choices, positive impact.

The ideology sounds compelling. The challenge is to ensure that it changes how businesses work, the choices we make, and the impacts we have.

“Smarter choices” is the first challenge. A key role for the business leader is to make decision, yet this has become much harder of a complex world of many trade-offs. Strategy is also about choices, the directions and priorities for the business, short and long-term.

“Smart” lies in the ability to align the business purpose with all its stakeholders, and to find an effective way in which together they can sustain enlightened value creation.

“Positive impact” is the second challenge. Long have we heard the mantra, “what gets measured gets done”. Therefore, leaders need to underpin their stakeholder ideology with a new set of performance metrics, which drive behaviours, define progress, and rewards.

“Positive” lies in the ability for the business to create a “net positive” contribution to the world in which it exists, some of which will be financial, but also non-financial.

In particular, I get frustrated when people get excited about new zero. Yes of course, we want and need to dramatically reduce the carbon emissions of business. But net zero sounds like a terrible compromise, and indeed we see many carbon emitters still seeking to offset their badness by planting forests of trees, and claiming net zero as a success.

Positive impact is therefore about value creation. Creating more value for all stakeholders.

Not as a compromise or trade-off. Not the short-termist mindset that will seek more value for shareholders at the expense of customers (less innovation) or employees (lower salaries) or society (negative impacts).

This is not utopia. It comes by creating that bigger “value pie” and then each taking a fairer, larger slices of a bigger whole.

It comes through a long-term perspective – how business wins through amazing and well rewarded people, who develop and deliver incredible products and services for customers, who are happy to pay more for them and stay loyal, with less harm to the environment and more good for society, all producing more and more sustained returns for shareholders too.

And as a results a sustainable, virtuous circle of value creation emerges. Sustained, shared, superior value.

Performance metrics, making it happen.

All this sounds great. But what gets measured gets done.

Stakeholder capitalism desperately needs a set of metrics for sustainable value creation.

To seek a coherent model for this across the business and investment communities, the WEF brought 140 of the world’s largest companies together, supported by the four largest accounting firms – Deloitte, EY, KPMG and PwC.

Their starting point was to align the existing approaches to measuring Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) performance and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). They agreed to seek common metrics for greenhouse gas emissions and strategies, diversity, employee health and well-being as factors to publish in annual reports alongside financial metrics.

The proposed metrics and recommended disclosures have been organised into four pillars that are aligned with the SDGs and ESG domains. They are

- Principles of Governance, aligned with SDGs 12, 16 and 17, and focusing on a company’s commitment to ethics and societal benefit

- Planet, aligned with SDGs 6, 7, 12, 13, 14 and 15, and focusing on climate sustainability and environmental responsibility

- People, aligned with SDGs 1,3, 4, 5 and 10, and focusing on the roles human and social capital play in business

- Prosperity, aligned with SDGs 1, 8, 9 and 10, and focusing on business contributions to equitable, innovative growth.

There is some way to go in getting close to “integrated reporting”, and in particular connecting financial and non-financial metrics which enable the more difficult trade-off decisions, and to understand the genuine long-term health of an organisation.

One approach, developed by BCG, is Total Societal Impact (TSI) which is a defined basket of financial metrics and non-financial assessments, brought together as one overall score. This enables leaders to consider the relative overall impact of different strategic options.

The challenge of course, is that any private company’s total value will always be financial, as long as it is possible for a buyer to come along and pay a certain price for it.

A new value map for business

Deloitte recently proposed a new Sustainable Value Map for business that brings together:

- An ROI-based approach: To facilitate the consideration of what value creation looks like for each stakeholder group, the map provides baseline ROI frameworks for each. This approach provides two levels of drivers for both the ROI numerator (returns) and for the denominator (invested resources). Note that the frameworks represent illustrative starting points, informed by popular sustainability frameworks. We expect companies and their stakeholders to have their own views on the value drivers, and we propose that they work together to develop their own formulations.

- Linked ROI frameworks: To aid the determination of the “input/output” relationships between the value creation frameworks, the SVM also provides examples of potential resource and impact flows across stakeholder groups. The nature of these dependencies will vary by company, but this starting point can help jump-start a deeper understanding and articulation by leadership teams.

- A system view: To promote the orchestrated management of value creation across stakeholders the SVM puts the value frameworks and inputs/outputs on a single page. This makes it easier to avoid tunnel vision around any single stakeholder and also draws out the recognition of relationships and dependencies not always apparent in traditional analyses.

Boden, a small military town in northern Sweden is set to become Europe’s centre for green steel, with a new steel plant, 900 km north of Stockholm.

Steel is usually made in a process that starts with blast furnaces. Fed with coking coal and iron ore, they emit large quantities of carbon dioxide and contribute to global warming.

The production of steel is responsible for around 7% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions. But in Boden, the new plant will use hydrogen technology, designed to cut emissions by as much as 95%.

Although the first buildings have yet to go up on the remote site, the company behind the project, H2 Green Steel, believes it’s on course to roll out the first commercial batches of its steel by 2025.

If it succeeds, it will be the first large-scale green steel plant in Europe, with its products used in the same way as traditional steel, to construct everything from cars and cargo ships to buildings and bridges.

Although much of Europe’s steelmaking industry dates back centuries, H2 Green Steel is a start-up that didn’t even exist before the pandemic.

When Northvolt opened Sweden’s first giant electric battery factory two hours south of Boden, it wanted to find a greener way of producing the steel needed to make the batteries, and H2 Green Steel emerged as a spin-off with funding from two of Northvolt’s founders.

The centrepiece of the new steel plant will be a tall structure called a DRI tower (DRI means a direct reduction of iron). Inside this, hydrogen will react with iron ore to create a type of iron that can be used to make steel. Unlike coking coal, which results in carbon emissions, the by-product of the reaction in the DRI tower is water vapour.

All the hydrogen used at the new green steel plant will be made by H2Green Steel.

Water from a nearby river is passed through an electrolyser – a process which splits off the hydrogen from water molecules.

The electricity used to make the hydrogen and power the plant comes from local fossil-free energy sources, including hydropower from the nearby Lule river, as well as wind parks in the region.

“This a unique spot to start with. You have to have the space, and you have to have the green electricity,” says Ida-Linn Näzelius, vice president of environment and society at H2 Green Steel.

H2 Green Steel has already signed a deal with Spanish energy company Iberdrola to build a green steel plant powered by solar energy in the Iberian peninsula, and says it’s exploring other opportunities in Brazil.

On home soil it’s got friendly competition from another Swedish steel company, Hybrit, which is planning to open a similar fossil-free steel plant in northern Sweden by 2026. This firm is a joint venture for Nordic steel company SSAB, mining firm LKAB and energy company Vattenfall, boosted by state funding from the Swedish Energy Agency and the EU’s Innovation fund.

While Sweden is leading the way when it comes to carbon-cutting steel production in Europe, it is important to put its potential impact in context, says Katinka Lund Waagsaether, a senior policy advisor at the Brussels-based climate think tank E3G.

H2 Green Steel hopes to produce five million tonnes of green steel a year by 2030. Global annual production is currently around 2,000 million tonnes, according to figures from the World Steel Association.

“The production capacity in Sweden will be a drop in the sea,” says Ms Lund Waagsaether.

Other ventures should help increase the proportion of green steel available in Europe.

These include, GravitHy, which plans to open a hydrogen-based plant in France, in 2027. German steel giant Thyssenkrupp recently announced it aims to introduce carbon-neutral production at all its plants by 2045. Europe’s largest steelmaker ArcelorMittal and the Spanish government are also investing in green steel projects in northern Spain.

Meanwhile, the EU is in the process of finalising a new strategy called the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, designed to make it more expensive for European companies to import cheaper, non-green steel from other parts of the world.

“I think it is important in that it’ll give industry the confidence to invest, because they can see that, at least in the European context, their steel will be competitive,” says Ms Lund Waagsaether.

She also points to a “a crucial window of action” between now and 2030, with around 70% of steelworks around the world in need of repair and reinvestment during this period.

Blast furnaces could be replaced or relined to extend their lifetimes, but a smarter long-term strategy, argues Ms Lund Waagsaether, would be to invest in switching to carbon-cutting production processes instead.

“The next eight years are crucial for making sure that companies and investors globally make decisions towards green steel production… which is going to ‘lock us in’ for another few decades.”

But whether the majority of big steel producers will follow this path is difficult to predict, says Lundberg. “I would say I’m hopeful, but we need to keep the pressure up.”

In Boden, the arrival of H2 Green Steel is being viewed as a major opportunity for job creation in an area that’s been crying out for new industries for decades.

The small military town shrunk after army budget cuts and closure of a large hospital in the region in the 1990s, resulting in thousands of people moving elsewhere to find work.

“This is our biggest opportunity in more than 100 years,” says the town’s Social Democrat mayor Claes Nordmark. “This will mean jobs, it will mean more restaurants, it will bring more sponsorship to our football and ice hockey and handball team and so on. It means everything for us.”

Neuzeller Klosterbräu, a German brewery, is revolutionising the future of beer.

The Brandenburg company has created a powdered lager that mimics the look and taste of beer on tap, just by adding water. Simply add two spoons of powder into a glass, adding water and giving it a stir, then sit back and enjoy an authentic German beer.

Helmut Fritsche purchased the Neuzeller brewery in 1992, which has been producing beer commercially for over 400 years, and is situated on the grounds of a 12th-century Catholic monastery, Neuzelle Abbey..

His son Stefan Fritsche, the brewery’s general manager, is idriven by the need to reduce the heavy carbon footprint beer exports generate, with one 355ml bottle equivalent to the emissions from driving a car one mile. By removing the extra weight created by glass and water, he believes he can reduce transport weight by 90 per cent.

Fritsche says that the possibilities of creating new beers doesn’t end there, and his team are currently exploring 40 other beverages from powder, adding to its current cherry beer, anti-ageing beer, and ginger beer inventions.

The “Anti-Aging-Bier”, which, in addition to the four cardinal ingredients of beer, adds spirulina and flavonoids in order to, supposedly, increase health and longevity, was launched in 2004, and claims to have double the anti-oxidant effect of other beers.

“We’ve also created bath beer, so you can even take a bath in the beer,” he said.

He says that the inspiration for new ideas come from a simple mantra, which he asks himself every day “How can I destroy my own company?” saying that if he doesn’t think actively about it, somebody else will.

Airbus is today the world’s largest manufacturer of airport – and seeks to shape the future, as a global pioneer in the aerospace – operating in the commercial aircraft, helicopters, defence and space sectors.

The Toulouse-based organisation has always been at the forefront of innovating new technologies, with a pioneering spirit that has redefined the aerospace industry. Airbus has a purpose defined as to “pioneer sustainable aerospace for a safe and united world.”

It’s a great aspiration, not just a responsibility, but inspiring too. It’s about “bringing people closer together, helping them unite and progress”. It’s about striving to “continually push the boundaries on what is possible to safeguard our world for future generations.”

- Download Peter Fisk’s Airbus strategy keynote “Pioneers and Transformers“.

- Read more from Peter Fisk on “Corporate Pioneers“.

Airbus is a leader in designing, manufacturing and delivering aerospace products, services and solutions to customers on a worldwide scale. With around 130,000 employees and as the largest aeronautics and space company in Europe and a worldwide leader, Airbus is at the forefront of the aviation industry.

It builds the most innovative commercial aircraft and consistently capture about half of all commercial airliner orders. This is built on a deep understanding of changing market needs, customer focus and technological innovation, to offer products that connect people and places via air and space.

Zero emission hydrogen-fuelled aircraft by 2035.

Cut to the chase. Air travel is one of the world’s largest contributors to carbon emissions. Every flight we add to our guilt, but continue to seek to stay physically connected in a changing world. Like driving our cars, not doing it feels unrealistic, let alone commercially disastrous to the leading commercial players. Instead every traveller, every airline company, every government, seeks a rapid reinvention of the industry.

We now see the rapid shift to electric cars, initially incentivised by government incentives, but now by a whole new generation of sexy EVs, plus the improving battery range and charging networks to support them. Similarly we see the shift in fashion, every store now packed with clothing from responsible or recycling materials. Or in food, the shift to organic, plant-based or eco-packaged products.

Not just to reduce our negative impacts, but to find new positive impacts too – to boost our wellbeing, to feel and look good, to be cool. Airbus, and indeed the entire air travel industry has a similar challenge. Yes to decarbonise, to find guilt free ways in which we can travel, but also to live better, to connect, to protect, and commercially to thrive in a world of change.

Creating a roadmap to a better future.

Spending some time with the strategy teams of Airbus in Toulouse this week, I started to appreciate the broad range of investments and initiatives not just to survive as an industry, but to create a better future too. While decarbonisation is essential, exploring and connecting the world is our choice. While purpose articulates a well-meaning intent, a roadmap of practical innovations makes it real, believable, and also exciting.

Wings are a great source of innovation. One recent prototype “bird of prey” design is a hybrid-electric, turbo-propeller aircraft for regional air transportation. It mimics the eagle’s wing and tail structure, and features individually controlled feathers that provide active flight control. In another project vertical wing-tip extensions resemble a shark’s dorsal fin significantly reduce the size of the wingtip vortex, thus reducing induced drag. Today, all members of the A320neo Family are fitted with sharklets as a standard.

Glenn Llewellyn is one of Airbus’ many hidden pioneers, creating the future of air travel. As vice president of the manufacturer’s ZEROe flight project – which Airbus says will get zero-emission hybrid-hydrogen aircraft to the market by 2035 – there’s a lot riding on his success. The aviation industry’s decarbonization roadmap reckons that more efficient, low- and zero-emission planes could account for 37 percent of the sector’s carbon emission reductions by 2050. He’s an inspiring, laid back guy, but with a passion to create a better future, for Airbus and all of us.

New strategies for new futures

We live in a time of great promise but also great uncertainty.

Markets are more crowded, competition is intense, customer aspirations are constantly fuelled by new innovations and dreams. Technology disrupts every industry, from banking to construction, entertainment to healthcare. It drives new possibilities and solutions, but also speed and complexity, uncertainty and fear.

As digital and physical worlds fuse to augment how we live and work, AI and robotics enhance but also challenge our capabilities, whilst ubiquitous supercomputing, genetic editing and self-driving cars take us further.

Technologies with the power to help us leap forwards in unimaginable ways. To transform business, to solve our big problems, to drive radical innovation, to accelerate growth and achieve progress socially and environmentally too.

We are likely to see more change in the next 10 years than the last 250 years.

- Markets accelerate, 4 times faster than 20 years ago, based on the accelerating speed of innovation and diminishing lifecycles of products.

- People are more capable, 825 times more connected than 20 years ago, with access to education, unlimited knowledge, tools to create anything.

- Consumer attitudes change, 78% of young people choose brands that do good, they reject corporate jobs, and see the world with the lens of gamers.

However, change goes far beyond the technology.

Markets will transform, converge and evolve faster. From old town Ann Arbor to the rejuvenated Bilbao, today’s megacities like Chennai and the future Saudi tech city of Neom, economic power will continue to shift. China has risen to the top of the new global business order, whilst India and eventually Africa will follow.

Industrialisation challenges the natural equilibrium of our planet’s resources. Today’s climate crisis is the result of our progress, and our problem to solve. Globalisation challenges our old notions of nationhood and locality. Migration changes where we call home. Religious values compete with social values, economic priorities conflict with social priorities. Living standards improve but inequality grows.

Our current economic system is stretched to its limit. Global shocks, such as the global pandemic of 2020, exposes its fragility. We open our eyes to realise that we weren’t prepared for different futures, and that our drive for efficiency has left us unable to cope. Such crises will become more frequent, as change and disruption accelerate.

However, these shocks are more likely to accelerate change in business, rather than stifle it, to wake us up to the real impacts of our changing world – to the urgency of action, to the need to think and act more dramatically.

The old codes don’t work

Business is not fit for the future. Most organisations were designed for stable and predictable worlds, where the future evolves as planned, markets are definitive, and choices are clear.

The future isn’t like it used to be.

Dynamic markets are, by definition, turbulent. Whilst economic cycles have typically followed a pattern of peaks and troughs every 10-15 years, these will likely become more frequent. Change is fast and exponential, uncertain and unpredictable, complex and ambiguous demanding new interpretation and imagination.

Yet too many business leaders hope that the strategies that made them successful in the past will continue to work in the future. They seek to keep stretching the old models in the hope that they will continue to see them through. Old business plans are tweaked each year, infrastructures are tested to breaking point, and people are asked to work harder.

In a way of dramatic, unpredictable change, this is not enough to survive, let alone thrive.

- Growth is harder. Global GDP growth has declined by more than a third in the past decade. As the west stagnates, Asia grows, albeit more slowly.

- Companies struggle, their average lifespan falling from 75 years in 1950 to 15 years today, 52% of the Fortune 500 in 2000 no longer exist in 2020.

- Leaders are under pressure. 44% of today’s business leaders have held their position for at least 5 years, compared to 77% half a century ago.

Profit is no longer enough; people expect business to achieve more. Business cannot exist in isolation from the world around them, pursuing customers without care for the consequence. The old single-minded obsession with profits is too limiting. Business depends more than ever on its resources – people, communities, nature, partners – and will need to find a better way to embrace them.

Technology is no longer enough; innovation needs to be more human. Technology will automate and interpret reality, but it won’t empathise and imagine new futures. Ubiquitous technology-driven innovation quickly becomes commoditised, available from anywhere in the world, so we need to add value in new ways. The future is human, creative, and intuitive. People will matter more to business, not less.

Sustaining the environment is not enough. 200 years of industrialisation has stripped the planet of its ability to renew itself, and ultimately to sustain life. Business therefore needs to give back more than it takes. As inequality and distrust have grown in every society, traditional jobs are threatened by automation and stagnation, meaning that social issues will matter even more, both globally and locally.

The new DNA of business

As business leaders, our opportunity is to create a better business, one that is fit for the future, that can act in more innovative and responsible ways.

How can we harness the potential of this relentless and disruptive change, harness the talents of people and the possibilities of technology? How can business, with all its power and resources, be a platform for change, and a force for good?

We need to find new codes to succeed. We need to find new ways to work, to recognise business as a system that be virtuous, where less can be more, and growth can go beyond the old limits. This demands that we make new connections:

- Profit + Purpose … to achieve more enlightened progress

- Technology + Humanity … to achieve more human ingenuity

- Innovation + Sustainability … to achieve more positive impact

We need to create a new framework for business, a better business – to reimagine why and redesign how we work, as well as reinvent what and refocus where we do business.

Imagine a future business that looks forwards not back, that rises up to shape the future on its own terms, making sense of change to find new possibilities, inspiring people with vision and optimism. Imagine a future that inspires progress, seeks new sources of growth, embraces networks and partners to go further, and enables people to achieve more.

Imagine too, a future business that creates new opportunity spaces, by connecting novel ideas and untapped needs, creatively responding to new customer agendas. Imagine a future business that disrupts the disruptors, where large companies have the vision and courage to reimagine themselves and compete as equals to fast and entrepreneurial start-ups.

Imagine a future business that embraces humanity, searches for better ideas, that fuse technology and people in more enlightened ways, to solve the big problems of society, and improve everyone’s lives. Imagine a future business that works collectively, self-organises to thrive without hierarchy, connects with partners in rich ecosystems, designs jobs around people, to do inspiring work.

Imagine also, a future business which is continually transforming, that thrives by learning better and faster, develops a rich portfolio of business ideas and innovations to sustain growth and progress. Imagine a future business that creates positive impact on the world, benefits all stakeholders with a circular model of value creation, that addresses negatives, and creates a net positive impact for society.

Creating a better business is an opportunity for every person who works inside or alongside it. It is not just a noble calling, to do something better for the world, but also a practical calling, a way to overcome the many limits of today, and attain future success for you and your business.You could call it the dawn of a new capitalism.

More from Peter Fisk

- Next Agenda of best ideas and priorities for business

- Megatrends 2030 in a world accelerated by pandemic

- Business Futures Project by Peter Fisk

- 49 Codes to help you develop a better business future

- 250 innovative companies shaking up every market

- 100 inspiring leaders with the courage to shape a better future

- Education that is innovative, issue-driven, action-driving

- Consulting that is collaborative, strategic and innovative

- Speaking that is inspiring, topical, engaging and actionable

Massive information overload is the defining feature of our age.

The incessant deluge threatens to drown us, yet within its excess lies almost everything of value today. The capacity to thrive on limitless information is now the single most important capability for success, yielding not just powerful insight, world-leading expertise, and better decisions, but also improved wellbeing.

In search of an escape from an everyday overload of messages, news, knowledge – and sometimes even an overload of new ideas – I turned to my good friend Ross Dawson, the Australian future thinker who I have done many events with. In his new book Thriving on Overload he offers a prescription for how to flourish in an accelerating world, showing you how to achieve superior outcomes in your career, ventures, investments, and life.

His thesis is all about choosing to thrive on overload―rather than being overwhelmed by it. He draws on his work as a leading futurist and 25 years of research into the practices that transform a surplus of information into compelling value. Develop the five intertwined powers that, together, enable extraordinary performance:

- Purpose: understanding why you engage with information enables a healthier relationship that generates success and balance in your life

- Framing: creating frameworks that connect information into meaningful patterns builds deep knowledge, insight, and world-class expertise

- Filtering: discerning what information serves us, using an intelligent portfolio of information sources, helps surface valuable signals above the pervasive noise

- Attention: allocating your awareness with intent, including laser-like focus and serendipitous discovery, maximizes productivity and outcomes

- Synthesis: expanding our unique capacity to integrate a universe of ideas yields powerful insight, the ability to see opportunities first, and better decisions

Scenario planning for information filtering

Scenario planning is one of the most effective of the arsenal of foresight methodologies, helping open the minds of participants as they discover for themselves alternative possibilities. One of the most useful outcomes is that it sensitises people to far better discern emerging trends, the “weak signals” that point to potential major shifts in the landscape.

The book explores some examples of using scenario planning for information filtering, noting that: A richly developed set of scenarios is far more valuable than a simple prediction. Useful scenarios provide not just an evocative picture of each future, but also a plausible and detailed narrative of the sequence of events that led there. Our minds grasp stories and mental pictures far better than abstract ideas or concepts. Having a small set of future worlds helps interpret almost any new information by seeing where it fits among the scenarios’ narratives. If it doesn’t fit anywhere, then it can be even more useful by prompting revision of the underlying thinking.

Of course scenario planning is most valuable in the practice itself, exploring possibilities and pathways that are relevant to the decisions that you are your organizations must make. Despite the massive strategic value of scenario planning, unfortunately only a minority of companies have the appetite for the in-depth process of exploring the possible futures of their industry.

However in your own information filtering and sense-making of our intensely complex world, you can draw on generic scenarios that are published by a variety of major organizations. Spending time with these can make it far easier to see the implications and import of emerging trends and news.

Here are a few scenarios that you may find useful to digest and apply to your sense-making.

World Economic Forum

World Economic Forum has a long history of deep scenario planning, formerly led by Ged Davis who came from leading Shell’s pioneering scenario planning group.

Their recent Four Futures for Economic Globalization shares perspectives on the global economy later this decade, providing a useful frame for unpicking directions in the macroeconomy and geopolitics.

Source: World Economic Forum – Four Futures for Economic Globalization

Source: World Economic Forum – Four Futures for Economic Globalization

U.S. National Intelligence Council

Various U.S. intelligence bodies, notably the CIA, have published global scenarios over the last decades.

While they clearly are U.S.-centric and focused on security issues, they do a good job of delving into underlying structural forces such as demographics, environment, technology, and societal tensions. Their most recent report Global Trends 2040 explores the landscape, dynamics, and provides a set of scenarios 20 years forward.

Source: National Intelligence Council: Global Trends 2040

Source: National Intelligence Council: Global Trends 2040

Shell

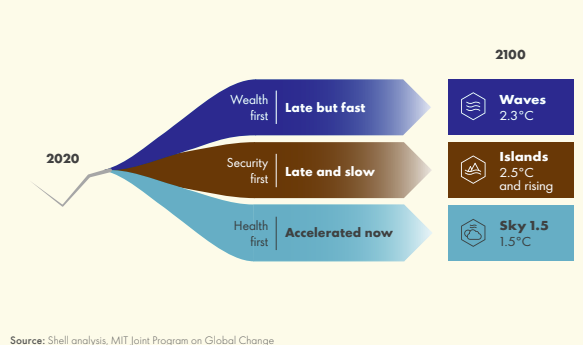

Shell originated modern scenario planning in the 1970s and it remains central to their strategic decision-making processes. They continue to share scenarios for energy and the environment. Their most recent report The Energy Transformation Scenarios examines in depth the scenarios and pathways for three different paths to the inevitable massive transition in energy.

Source: Shell: The Global Energy Transformation Scenarios

Source: Shell: The Global Energy Transformation Scenarios

Other scenarios

This is of course a very small sampling of the public scenarios available that you can use for your own sense-making.

In particular the major consulting firms all publish scenarios for the future of a wide variety of industries, which can be extremely useful for leaders in those sectors.

You will get the most value in identifying the most relevant information by creating your own sets of scenarios, but using publicly available ones can also be very helpful with minimal effort.

Cycling is a sport of connoisseurs. They love their coffee, in France they love their pastis, and they love their bikes and gear.

Riding at the heart of a Sunday morning peloton is as much social as physical, and so Rapha designed to create premium cycling gear, and coffee shops – or Cycle Clubs – where enthusiasts can meet.

Walk into a Rapha Cycle Clubs – in London or New York, Sydney or Osaka – and you can see, smell and touch a love of cycling. Rapha, founded in London’s Covent Garden by Simon Mottram in 2004, has grown rapidly, building a direct relationship with consumers, through events and online community, as well as its coffee-shop stores. There are also line extensions into luggage, skincare, books and travel, plus a co-branded range with designer and cycling enthusiast Paul Smith.

Rapha is a brand that polarises opinion. For some it has created the ultimate in high performance equipment, dedicated to a sport that breeds passion and perspiration. For others, it is over-priced and over-designed vanity wear for middle-aged men who squeeze into their posh lycra for a weekend ride. Whichever your view, it gets talked about. Especially items such as the $450 pair of yak-leather cycling shoes, or the $150 pro-glide coffee tamper, to flatten your coffee like the best baristas after your run.

Enabling more

Microsoft seeks to “empower every person and every organisation on the planet to achieve more”, or as Satya Nadella says, “to make other people cool, not ourselves”.

I worked with Microsoft to help them achieve this with business customers. Traditionally sales and technology experts had gone out to clients seeking to sell products, or in today’s model, subscriptions. It was largely product push, with diminishing returns. We stepped back and asked how can we help clients to achieve more?

The transformation was to help them do what they want to do – to reach new markets, innovate new solutions, transform their own businesses. Instead of a relationship starting with a list of product options, we started by listening, and then together using the combined expertise and ideas of what is possible, to develop a new plan for growth.

If a brand is about what it enables people to do, rather than what it does, then it follows that a great brand enables people to achieve even more than they could imagine, or to do so in a better way, with greater success.

Enablement has become a key word in branding. Brands do more for their customers in three primary ways

- Educating people: helping customers to learn how to use and apply their products and services in better ways, to get the best out of them.

- Enabling people: collaborating with customers to achieve more, using products better, changing how they work, to do more.

- Enhancing people: adding to the solution of customers, adding new ideas from other places, and transforming their own performance levels.

Apple stores are busier with education workshops – how to create better sales presentation, build a better website for your business, do your tax return correctly – than people seeking to buy or repair their devices. Lululemon yoga wear stores are transformed into yoga studios at regular intervals during the day, a place to do what you love, not just to prepare for it. M&C Saatchi ad agency has rooms for each of its clients, dedicated to their brands and campaigns, where they can work together as joint teams.

Building a brand community

A brand community is a group of consumers who invest in a brand beyond what is being sold.

Think about some of the great examples of brand communities through which people engage with brands and businesses today, influencing what they buy, who they trust, and how they achieve more. From Lego Ideas to TED Talks, Xbox Ambassadors to Nike’s Run Club, Disney’s D23 Fans to Bayern Munich’s supporter’s club.

Here are some of the most famous:

- Harley Owners Group: recognised that owners loved much more than the bike, it was the freedom to ride the roads, the thrill to ride together, to hang out at Ace Cafes, to share their passion for life.

- Glossier: became the world’s fastest growing beauty business, emerging out of a Vogue editor’s blog followers, to become a community where consumers share ideas and advice, but also co-create their products.

- Lego Ideas: about more than colourful plastic blocks, Lego is derived from the Danish for “creative play”. It is about creative development and expression, which is why its online community is a vibrant space for contests, photos and new ideas.

- Behance: Adobe’s platform for showcasing and discovering great creative work now has over 10 million participants, both professional designers and amateurs, including exclusive tools and project collaboration spaces.

- Spotify Rockstars: bringing together people who love music, encouraging discussion and recommendations, rewarding and ranking the most active, and also a platform for discovering new talent.

Communities built on passions

From meaningful consumer retention to new sources of revenue, unfiltered consumer insight and predictable cashflows, branded communities offer many opportunities for a business to drive growth:

- Enhance consumer experiences – how people achieve more, collaborate and recommend, and create new content together.

- Ongoing engagement – how people engage with brands continuously, not just at moments of promotion or purchase.

- Know consumers better – 67% of businesses use communities to gain deeper insights to drive better focus and innovation.

- Increase brand exposure and credibility, making it easier to sell without selling – typically 35% increase in brand awareness.

- Reduce consumer support costs – 49% of businesses with online communities report cost savings of around 25% annually.

- Improve retention and advocacy – improving retention by 42%, tripling cross-selling, and people pay more too.

Building a great brand community has three foundations:

- Consumer: starting with your target audience, with a captivating reason for members to join the “tribe”, be it a shared cause or interest, from hip-hop music, to a love of science fiction novels, or a desire to get fit.

- Collaboration: engaging with other people, facilitated by the brand and its community platform, which might take the form of discussions, co-creation and recommendations.

- Content: the glue that makes the community work beyond products. These might take the form of newsletters, events, videos, other products, discussion boards, merchandise, exclusive offers, and much more.

Underpinning this is a business model that ensures that the community adds real value to its members, but also commercially works for the organisation. For members, this means it adds value beyond the brand’s conventional products and services, typically enabling them to use them better, and get more from them. For business, this means having a business model that drives incremental revenue growth. This might be in the form of consumer retention, selling more or different products, but also other types of content, and potentially a subscription to belong.

Communities are one of the most powerful ways a brand can grow, often exponentially.

© Peter Fisk 2023.

Excerpt from “Business Recoded” by Peter Fisk

- Download Peter Fisk’s keynote “Pioneers and Transformers” for Airbus, March 2023.

I work with many organisations – typically their boards and executive teams – to help them explore, define and shape their futures.

A typical project might start with “we need a new strategy” but that would quickly become more complex, as we realise that the organisation lacks a fundamental direction – purpose, vision. This gives us context and direction, a framework in which to develop a strategy. A strategic framework with purpose, vision, strategy and goals is a useful start.

Strategy is ultimately about making choices. What we will do and not. This is where is can getter harder, but also clearer. Many organisations lack a framework to make these choices – not just in terms of financial, but the broader value set, and stakeholder engagement, which determines which financials matter most.

However the most interesting discussion often becomes about culture, of the business holistically, and therefore of its leaders too. What’s their distinctive role? How will they behave, add value, and lead? The answers usually link to the strategic choices too.

A number of recent clients said their vision was “To be the pioneer in ….”. If that’s the case, how will the be a “pioneer”?

Airbus, for example, defines its purpose as “pioneering sustainable aerospace for a safe and united world”, or in the Middle East, Al Ghurair, who started out as pearl divers in Dubai Creek, seek once again to be “pioneers, in search of better”.

I’m not sure why pioneer has become such a popular phrase. I get that markets are complex and dynamic, that disruption is everywhere, but itself not the answer. I get that most organisations need to transform themselves, to be fit for the future. But this word pioneer keeps coming up.

Look to the definition of pioneer, and you will find “a person who is among the first to explore”, or as a verb “to develop or be the first to use or apply (a new method, area of knowledge, or activity).”

Business Chemistry

So what does a pioneer look like in business, and particularly in the C suite of larger, mature companies?

“Business Chemistry” is a framework that describes distinct patterns of behavior that can be harnessed to improve individual interactions and influence strategy. Developed by Deloitte in conjunction with scientists from the fields of neuro-anthropology and genetics, The framework identifies four dominant personality patterns: Drivers, who value challenge and generate momentum; Guardians, who value stability and bring order and rigor; Integrators, who value connection and draw teams together; and Pioneers, who value possibilities and spark creativity.

Each of us is a composite of the four work styles, though most people’s behavior and thinking are closely aligned with one or two. All the styles bring useful perspectives and distinctive approaches to generating ideas, making decisions, and solving problems. Generally speaking:

- Pioneers value possibilities, and they spark energy and imagination on their teams. They believe risks are worth taking and that it’s fine to go with your gut. Their focus is big-picture. They’re drawn to bold new ideas and creative approaches.

- Guardians value stability, and they bring order and rigor. They’re pragmatic, and they hesitate to embrace risk. Data and facts are baseline requirements for them, and details matter. Guardians think it makes sense to learn from the past.

- Drivers value challenge and generate momentum. Getting results and winning count most. Drivers tend to view issues as black-and-white and tackle problems head on, armed with logic and data.

- Integrators value connection and draw teams together. Relationships and responsibility to the group are paramount. Integrators tend to believe that most things are relative. They’re diplomatic and focused on gaining consensus.

The Deloitte study found that two of the four personality types account for almost two-thirds of the sample: Pioneers (36%) and Drivers (29%), with Guardians (18%) and Integrators (17%) accounting for the rest.

Those results varied, however, across C-suite roles, as well as by company size, industry and gender. While Pioneers were more prevalent in the C-suite overall, for example, CFOs were more likely to be Drivers (37%) and Guardians (26%). In the largest organizations in the sample (those with more than 100,000 employees) the proportion of C-suite executives who were Drivers (38%) outpaced the proportion of Pioneers (29%). In organizations with more than $10 billion in revenues, Drivers and Pioneers each represented 34% of the C-suite.

A commentary in the WSJ suggests that while C-suite executives are similar in many ways to a typical professional in terms of practicality, duty, discipline, imagination, relationship orientation, openness to experimentation and expression, they differ in particular ways related to their perspectives on approaching problems and interacting with others. As compared with the general business population, C-suite executives in this sample are significantly more likely to:

- Be big picture thinkers who are competitive and willing to tolerate conflict

- Make decisions more quickly without worrying about the popularity of those decisions

- Be quantitative and comfortable with ambiguity

When 13,885 professionals in a separate study were asked what they most aspire to be when it comes to their careers, the overwhelming majority of Drivers (68%) and Pioneers (67%) chose “Leader.” Integrators and Guardians were more evenly split across a range of aspirations.

HP is one example of a large corporation seeing to rekindle its pioneering spirit.

They use Bill Hewlett and David Packard’s original garage, where they founded the business, as a symbol of what it takes to be a pioneer. Here with their “Rules of the Garage”:

Pioneering leaders

Pioneering leaders are adventurous — driven to keep seeking bigger and better roles, products, and experiences. They inspire a team to venture into uncharted territory. We get caught up in their passion to grow, expand, and explore.

Be aggressive about exploring opportunities

This is a great dimension to draw upon if you’re an entrepreneur in the first stages of building a business or brand. It’s also good to develop these behaviors during times when things seem to be just coasting along. . The pioneering leader reminds us that innovation doesn’t happen without active exploration. In other words, the next big thing isn’t hiding under your desk.

“Leaders are pioneers—people who are willing to step out into the unknown. They search for opportunities to innovate, grow, and improve.” say James M. Kouzes and Barry Z. Posner, The Leadership Challenge

- 5 Behaviors of Leaders Who Embrace Change, Harvard Business Review

- 5 Ways Leaders Act Like Rebels (That’ll Make You Successful, Too), Forbes

- How Transformation-Ready Leaders Learn, strategy + business

Leaders lead change and stretch the boundaries

Pioneering leaders aren’t afraid to do what’s never been done before. They encourage growth for the organization and for the people around them. They stay current with best practices and opportunities to stretch beyond the status quo. You might be working hard to create a stable environment for your employees, but you need to be sure you aren’t also quashing the creativity of the entrepreneurial spirit around you.

“Let people know that innovative thinking is a part of everyone‘s job, regardless of their function or level of responsibility” says Susan Gebelein et al, Successful Executive’s Handbook

- Why the Best Leaders Act Like Playful Puppies, Entrepreneur

- Why Challenging The Status Quo Will Make You A Better Leader And How To Do It, CoSchedule blog

- Challenge the Process by Creating Original Ideas, Flashpoint Leadership

Learn to take leaps of faith

Careful planning has its place and its rewards, but sometimes bold action is necessary. The first to market often has the advantage. The faith you show in your ideas inspires others. Not taking a chance can present its own dangers. If you’re risk adverse, allow yourself time for a reasonable amount of analysis and then act. Don’t let the research, risk assessments and worry stop you from taking the leap.

“The truth is that challenge is the crucible for greatness. … And the truth is also that you either lead by example or you don’t lead at all. You have to go first as a leaders” say James M. Kouzes and Barry Z. Posner, The Truth About Leadership

- 5 reasons why bold leaders are remarkably successful, Ladders

- You Win Or You Learn: Risk-Taking For Leaders, Forbes

Thomas Edison said “I have not failed 10,000 times, I’ve successfully found 10,000 ways that don’t work.”

In writing my latest book, Business Recoded, I’ve explored many fascinating stories of our changing business world, discovered some incredible organisations, and interviewed some truly inspiring leaders.

I’ve also come across quite a few quirks of the system – effects and paradoxes – which, whether they are true or not, make you think. Here are a few.

Consider these little examples from social behaviour:

- Abilene Paradox: A group decides to do something that no one in the group wants to do because everyone mistakenly assumes they’re the only ones who object to the idea and they don’t want to rock the boat by speaking up.

- Luxury Paradox: The more expensive something is the less likely you are to use it, so the relationship between price and utility is an inverted U. Ferraris sit in garages; Toyotas get driven.

- Friendship Paradox: On average, people have fewer friends than their friends have, because people with an abnormally high number of friends are more likely to be one of your friends.

I love a good paradox.

Particularly for finding new ideas for innovation. I remember former P&G CEO AG Lafley searching for paradoxes in his markets – apparent contradictions in consumer behaviour, two aspirations much seemed impossible together, and then seizing on it as the opportunity to innovate.

But paradoxes equally occur in the process of innovation. However hard you try to design the perfect innovation machine, it will always be the outlier ideas, people or solutions which have the greatest impact. They add abnormality to routine normality. They inject creative divergence. They break the rules.

A recent Forbes article described 12 paradoxes of the innovation process:

1. Innovative organisations have strong innovation machines but recognize that some of the best ideas come from outside the machine … think of 3M’s Post-it Notes that emerged from an insight watching page markers fall out of church hymn books.

2. Big, disruptive ideas are alluring, but small, incremental ideas often pay the bills … think of Apple’s profitable evolution rather than revolution under Tim Cook, after the blockbuster years of Steve Jobs. Air Pods were probably the biggest innovation.

3. Small, incremental ideas often pay the bills, but big, disruptive ideas may be necessary to secure an organisation’s place in the long-term … think of Google’s moonshot program, seeking to find the big ideas to change paradigms and leap forwards.

4. Siloes can be anathema to innovative thinking, but are often necessary for depth and execution … at BDS, the Singapore-based bank, the customer service teams were able to go much deeper in understanding service issues, and innovating new solutions.

5. Process creates discipline, but also can suffocate good ideas … so many good ideas are killed during a process that has checks and metrics designed to deliver convention not innovation, the best ideas rarely survive a core business treatment.

6. Psychological safety breeds better cultivation of ideas, but innovation is measured by results … but which results? If you seek short term sales glory, you are rarely going to have the time to create the future, or engage the outlier audiences.

7. Communication around innovation is key internally, but confidentiality is necessary to keep ideas from external competitors … the secret becomes so secretive that it never spreads, staff are some of your best ambassadors.

8. Failing fast and learning fast reduce wasted time, energy, and money, but artifacts allow for future reconstitution and re-use … every failure is partly a success, a small step forwards even if it doesn’t feel like it.

9. Timing of ideas is essential, but an idea that fails one year can succeed in another under different circumstances or with the right tweaks … hence the importance of having a portfolio of innovations, a cupboard full to unlock at the right time.

10. Cannibalizing existing business represents a threat to orthodoxy, but also prevents competitors from doing so … Coca Cola thought long and hard about entering water and juice categories, but then realised opportunities beats threat.

11. Successful innovation teams include deep content expertise and experience, but also generalists and process experts who look through a different lens and ask new questions.

12. Innovators often feel like imposters, but don’t realise that feeling is part of a growth mindset … look at the way in which Satya Nadella has taken Carol Dweck’s mindset model to reinvent Microsoft … growth mindset is about continues discovery.

The noseride is one of surfing’s peak moments: part fluid dynamics, part magic.

But how does noseriding actually work? What makes this suspension between sea and sky even possible?

Patagonia’s short movie “The Physics of Noseriding” explores the question through the eyes of Namaala, a young surfer whose people were flying on the water before the world even knew what surfing was.

Her curiosity invites us to examine the sensation of levitation that unfolds as wave, surfboard and surfer come together for surfing’s fluid dance.

Noseriding is when the surfboard interacts with the wave.

The most common thing you’ll hear is that water on the tail creates downward pressure which creates lift in the nose allowing it to hold your weight. Essentially your board is acting like a lever and as long as there’s enough pressure on the tail, you’ll be able to stand on the nose. One thing to keep in mind is that this will only work when you’re in the *pocket* of the wave.

I love this. Because it’s all about passion.

The passion of the surfer in search of perfection. And the passion of Patagonia, the brand, for what people seek to do.

We all know Patagonia as the protest brand – fighting against climate change, fighting for social rights. And in particular how founder Yvon Chouinard recently chose to “give away” his multi-billion dollar business to a charitable foundation, which will ensure that every dollar of profit (typically $100 million every year) goes to fighting climate change.

We also know the story of how Patagonia started – about Chouinard, his passion for the outdoors, from climbing to fishing.

So it’s refreshing to see the passion, as well as the protest – seeking to create a better world – so that we can enjoy the beauty of the natural environment, the thrill of outdoor sport, and the obsession for perfection.

ChatGPT has dominated the tech headlines of recent months. The OpenAI interface has become a symbol of progress for the ways in which knowledge is evolving, and challenging human minds.

Of course AI is all around us. Wake up to check your health on your Apple Watch. Click on the weather forecast. Or just ask Siri. Jump in your car, and Google Maps becomes your intelligent navigator, using realtime traffic data to find the best route.

At very least, ChatGPT, which was only ever meant to be a prototype to test human engagement, has alerted to the way in which AI is challenging the human brain. Yes of course, it can source and synthesise huge amounts of information, and quantum computing will accelerate that millions of times faster.

But it still struggles to think, to imagine, to create. That, so far, is still a human quality, isn’t it?

Humans and technology

Digital anthropology focuses on the relationship between humans and today’s broad range of technologies – from computing and robotics, mobile phones and gaming, data and AI, crypto and NFTs.

How do people engage with these technologies? What are the ethics? Who is in control?

One of my expert faculty at IE Business School is Verónica Reyero, a social anthropologist and founder Anthropologia 2.0. She has spent many years exploring the field, and helping business leaders to make sense of this changing world.

In a recent discussion, we started by reflecting on society’s obsession today with social media. “Why do people post?”. What drives people to share every moment of their lives with the world. The millions of photos posted, popularity measured in likes. The influence of people on each other, the shift in trust from institution to community, the rise of tribes across traditional boundaries.

A great insight into this topic comes from UCL Why we post research project

Three factors dominated our discussion

- Identity – how we build our identity in a digital world – how we present ourselves, and how others perceive us.

- Relationships – how we connect with each other – our chosen communities, and equally as societies, nations and tribes.

- Value – how we decide the worth of products and services – of time, of connections, of possessions.

As examples, why pay $6000 for a pair of Nike RTFKT CrytoKick virtual sneakers, to wear on your Fortnite avatar, but which you will never wear in the real world?

Digital anthropologists

Most anthropologists who use the phrase “digital anthropology” are specifically referring to online technology. The study of humans’ relationship to a broader range of technology may fall under other subfields of anthropological study, such as cyborg anthropology.

The Digital Anthropology Group (DANG) is classified as an interest group in the American Anthropological Association. DANG’s mission includes promoting the use of digital technology as a tool of anthropological research, encouraging anthropologists to share research using digital platforms, and outlining ways for anthropologists to study digital communities.

Cyberspace itself can serve as a “field” site for anthropologists, allowing the observation, analysis, and interpretation of the sociocultural phenomena springing up and taking place in any interactive space.

National and transnational communities, enabled by digital technology, establish a set of social norms, practices, traditions, storied history and associated collective memory, migration periods, internal and external conflicts, potentially subconscious language features and memetic dialects comparable to those of traditional, geographically confined communities. This includes the various communities built around free and open-source software, online platforms such as 4chan and Reddit and their respective sub-sites, and politically motivated groups like Anonymous, WikiLeaks, or the Occupy movement.

A number of academic anthropologists have conducted traditional ethnographies of virtual worlds, such as Bonnie Nardi’s study of World of Warcraft or Tom Boellstorff’s study of Second Life.

Anthropological research can help designers adapt and improve technology. Australian anthropologist Genevieve Bell did extensive user experience research at Intel that informed the company’s approach to its technology, users, and market.

Human algorithms

“A Human Algorithm: How Artificial Intelligence Is Redefining Who We Are” is a 2019 non-fiction book by American international human rights attorney Flynn Coleman. It argues that, in order to manage the power shift from humans to increasingly advanced artificial intelligence, it will be necessary to instil human values into AI, and to proactively develop oversight mechanisms.

Coleman argues that the algorithms underlying AI could greatly improve the human condition, if the algorithms are carefully based on ethical human values. An ideal AI would be “not a replicated model of our own brains, but an expansion of our lens and our vantage point as to what intelligence, life, meaning, and humanity are and can be.” Failure in this regard might leave us “a species without a purpose”, lacking “any sense of happiness, meaning, or satisfaction”. She states that despite stirrings of an “algorithmic accountability movement”, humanity is “alarmingly unready” for the arrival of more powerful forms of AI.

To realize AI’s transcendent potential, Coleman advocates for inviting a diverse group of voices to participate in designing our intelligent machines and using our moral imagination to ensure that human rights, empathy, and equity are core principles of emerging technologies.

Accelerating change

One thing is certain. Tech will only increase in its pace of disruption, adoption and impact.

We will see the evolution of space exploration, from NASA’s Artemis mission, humans landing on Mars, and the interplanetary internet system going online. To the launch of the Starshot Alpha Centauri program, and quantum computers designing plants that can survive on Mars. On Earth, tech evolves with quantum computers and Neaulink chips.

People will begin living with bio-printed organs. Humans record every part of lives from birth. And inner speech recording becomes possible. And what about predictions further out into the future, when humans become level 2 and level 3 civilizations.

When NASA’s warp drive goes live, and Mars declares independence from Earth. Will there be Dyson structures built around stars to capture their energy. Will they help power computers that can take human consciousness and download it into a quantum computer core. Allowing humanity to travel further out into space.