Both only 24 at the time, they leased a building in Fraserburgh, got some scary bank loans, spent all their money on stainless steel and started making some hardcore craft beers. They brewed tiny batches, filled bottles by hand and sold their beers at local markets and out of the back of our beat up old van.

Since then, the company has grew rapidly, but holding on to its irreverent mindset.

- Read the new BrewDog Blueprint

- Read the latest Sustainability Plan

- Read the latest Annual Report

Watt himself is known for explosive, bombastic proclamations in the press: His press releases include “F**k the rules” announcing the launch of his new business book and an update on BrewDog’s crowdfunding campaign that quotes him as saying: “We’ve not just broken a record, we’ve smashed through it with a monster truck”.

But in person, when we meet to discuss his new entrepreneurial advice book “Business for Punks,” Watt is softly spoken, cheery, and pretty harmless. The closest he gets to swearing is saying “balls.”

Beer for Punks

“I just wanted to outline our off-the-wall, slightly anarchic approach to business so other people could see what we’ve done and realise that you don’t have to do what you’re supposed to do, you don’t have to follow the status quo, and you can do things on your own terms,” he says, explaining his motivation for writing the book.

“Before I set up the business I was captain of a fishing boat. I’d never done a business before, I’d never been involved in business. We didn’t know how things were meant to be done so we went ahead and did things on our own terms, in our own way, and almost inadvertently created a whole new approach to business along the way.”

BrewDog was one of the first breweries in Britain to pioneer a new wave of hoppy, American-style “craft” beers and its Punk IPA is one of the most popular and recognisable brands of British craft beer.

Watt and co-founder Martin Dickie became two of Britain’s most successful entrepreneurs in recent years, building a network of bars across the UK, and and then looking across the world.

Watt likes to talk up his “anarchic” approach and chapters of his book include “Finance for visionary renegades,” “Marketing for postmodern dystopian puppets,” and “Sales for postmodern apocalyptic punks.”

But look past the flowery language and the advice in the book is pretty level-headed stuff — keep an eye on the bottom line, know your customers, and make sure staff are happy.

“The startup phase, finance, the bit about staff, company culture, finding time — all these things can apply to almost anyone in any business,” he says.

While Watt may not have run a business before BrewDog, but he’s clearly been keeping an eye on things, pointing to Apple, Zappos, and Danish restaurant Noma as good businesses based around a “cause” in the book.

BrewDog’s passion is good beer. Watt says: “As a company we focus on two things — our beer and our people. We have done some sort of high-octane, risky, edgy, marketing things but they’ve all been done to increase peoples’ awareness and understanding of good beer.”

But how “risky”, “edgy”, and “anarchic” is BrewDog these days? It’s beer is stocked in huge supermarkets like Tesco, Sainsbury’s, and Waitrose.

“Our mission is to make other people as passionate about great beer as we are and we can’t do that if we don’t have the means to get the beer into people’s hands,” Watt says. “We’re about getting people excited about beer and do to that we need to get beer to market by any means possible.”

Equity for punks

BrewDog pioneered the idea of equity crowdfunding in the UK, launching its first “Equity for Punks” campaign on its website in 2009.

Watt recommends crowdfunding to entrepreneurs, saying: “We love the Equity for Punks model. We’ve now raised over £20 million ($30.5 million), we’ve got a community of over 14,000 Equity for Punks investors who are advocates, who are ambassadors, who are principally linked to our business.

“We just love the fact that our business is owned by people who love fantastic beer as much as we do.”

The money BrewDog raises is going to be put towards everything from expanding its network of bars to opening a beer-themed hotel in Scotland and breaking into the “craft” spirits business. But BrewDog is still, and always will be, a beer company, Watt says.

“I don’t think it is more than just beer,” he tells me. “The hotel tacks on to the hospitality side of our business and we’re not looking to open a chain of hotels, we’re just looking to open one hotel up in the north east of Scotland.”

He adds: “I think the spirits tacks on nicely if you look at people like [US craft breweries] Anchor Brewing, Dogfish Head, Rogue, New Holland. With a beer, we’re more than 50% there to making a fantastic tasting spirit and we just want to do some more experimentation in that space. But the company is very, very much about beer.”

Watt says he and co-founder Martin Dickie would never sell the business to one of the big brewing conglomerates.

That’s not to say we wouldn’t exit at some point but there’s no plans at the moment,” he says, “and if we did, instead of selling to a bigger company, it would be a management buyout or to release some more equity to our Equity for Punk holders.”

But then it all went wrong.

In 2020, BrewDog became the world’s first carbon-negative beer company and one year later, the company received its BCorp certification but also came under scrutiny after some employees accused the company of having a toxic work culture. BrewDog responded with an independent culture review and lots of new actions, for example, the creation of an Employee Representative Group.

A new start. A new blueprint.

In 2022, BrewDog released its new BrewDog Blueprint offering a nice glimpse into their new business practices and plans.

It was reported that the company received more than 1,000 job applications in the 10 days after the publication of the blueprint.

Here are some of the initiatives driven by the new blueprint:

People Blueprint

Employee-Ownership Programme

“Our Hop Stock programme will ensure that we are all in this together as we build the future of BrewDog.”

- Founder James Watt is giving away 5% of his BrewDog stake (worth around £100m) to its employees.

- This means, 3.7m shares in BrewDog will be distributed evenly amongst all employees with each team member receiving approximately £30,000 per year in shares over the next 4 years.

Profit-Sharing

“We want to create a radically new business model for hospitality – one that firmly puts the people who make the real difference in our bars, those who look after our customers every day, at the very core of what we do.”

- Each BrewDog Bar is going to share 50% of its profits evenly with team members.

- Profit share allocation is based on hours worked – so General Managers and bar crew share in the profits in the same way.

- Financial details will be shared fully transparent with all team members, every month

Alumni Club

“With the BrewDog Alumni Club we want to formally recognise the contribution that all of our former team members have made and also thank them for their efforts.”

- Free to join alumni club for all former team members.

- Benefits include amongst others a lifetime discount of 10% in all bars and on the online shop, a free 12 pack of beer every December and an invite to a yearly alumni social event

Sabbatical

- Employees get 4 weeks full paid leave – beyond their normal holiday allocation for every 5 years of service.

Salary Cap

- No-one can join the company for a salary higher than 7x of what the lowest full-time salary at Brewdog is.

Mental Health First Aiders

- By the end of 2022, 10% of Brewdog staff will be qualified as mental health first aiders.

- A monthly wellbeing lab covers topics from men’s mental health to menopause.

DEI Forum

- A crew-led Diversity, Equity and Inclusion forum meets weekly to drive actions within the company.

Planet Blueprint

Carbon Negative Business

“We believe that our carbon is our problem.”

- In August 2020, BrewDog became the world’s first carbon negative beer business. The company removes twice as much carbon from the air as they emit, every single year.

- BrewDog bought 9,308 acres in the Scottish highlands that will be restored and rewilded (including peatland restoration and native tree planting). The land is capable of pulling up to 1 million tonnes of carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere.

- The project was developed in partnership with independent sustainability expert Prof. Mike Berners-Lee.

Carbon Reduction Strategy

“When we count our carbon, we count all of it; this includes all direct emissions which occur at our breweries and bars, the emissions from the electricity we purchase, as well as the emissions of our entire upstream and downstream supply chain, globally.”

- Brewdog invests close to £50m to reduce their environmental impact. Their carbon footprint has already been reduced by 20% vs its 2019 baseline, with a 35% reduction being the target for 2023.

- How?

- A Bioplant was commissioned that will recycle and reuse most of the company’s wastewater. The plant will also generate green gas to power the brewery and delivery trucks.

- CO2 recovery by capturing the CO2 produced by the bioplant and during beer fermentation is planned.

- All of BrewDog’s UK business is already wind-powered, and all other global businesses purchase green electricity. Some, like BrewDog’s Australian brewery is solar-power driven.

- BrewDog is in the process of swapping out all of the company’s delivery vehicles to low-carbon powered alternatives.

- At BrewDog bars it’s also all about switching to eco-friendly consumables, building local brewing sites to shorten the supply chain, reducing waste, carbon footprint labeling, and 50% vegan and veggie menus, amongst other things.

While it hasn’t been an easy ride, Brewdog is back, still popular, still growing. But seeking to balance its irreverent style with a more responsible one too.

Business for Punks

Watt’s book Business for Punks bottles the essence of Brewdog an accessible, honest manifesto, including mantras like

- Cash is motherf*cking king … Cash is the lifeblood of your company. Monitor every penny as if your life depends on it—because it does.

- Get people to hate you … You won’t win by trying to make everyone happy, so don’t bother. Let haters fuel your fire while you focus on your hard-core fans.

- Steal and bastardise from other fields … Take inspiration freely wherever you find it— except from people in your own industry.

- Job interviews suck … They never reveal if someone will be a good employee, only how good that person is at interviews. Instead, take them for a test drive and see if they’re passionate and a good culture fit.

Here is a longer list of the best moments and messages from the book, delivered in typically provocative yet inspiring style:

- At BrewDog we reject the status quo, we are passionate, we don’t give a damn and we always do something which is true to ourselves. Our approach has been anti-authoritarian and non-conformist from the word go.

- Ultimately for a crew to be effective leadership needs to come from the top down, the bottom up and everywhere in between.

- Michael Jackson led to Martin and I deciding to take the plunge, follow our dreams and start our very own craft brewery. Michael, upon tasting one of our home-brewed concoctions, told us to quit our jobs and start brewing beer. It was the last bit of advice we ever listened to.

- Rip up those stuffy old text books, reject the status quo, tear down the establishment and embrace the dawn of a new era.

- The decisions you make during your business’s formative months will define your place in the world. They will be the most monumental decisions you will ever make, shaping your fledgling business in ways you cannot yet imagine. So you’d better buckle up, hold tight and step up to the challenge. You will need to make sure your ideas, and their realization, are nothing short of awesome.

- Businesses fail. Businesses die. Businesses fade into oblivion. Revolutions never die. So start a revolution, not a business.

- Your biggest challenge from day one is to give people a reason to care, and that reason has got to be your mission.

- The market for something to believe in is infinite. You need to give people something to believe in.

- If money is your motivation then you need to be the greediest, meanest son of a bitch on the planet to make a business work. Solely money-focused businesses do exist, but I don’t like being around them or their people.

- Assume no one will care, assume no one will give a damn, assume no one will want to listen. Then figure out how to make people want to care about what you do. If you can’t, then your business is doomed.

- Twenty-first-century consumers increasingly want to align themselves with companies and organizations whose missions and beliefs are compatible with, and enhance, their own belief systems.

- Advice is for freaks and clowns. The thing about being driven is you need to know your own way.

- The only thing you learn from mistakes is that you are not good enough and that you need to get better.

- Don’t follow when you can lead.

- Be a selfish bastard. Seriously, you have to be. If you’re not 110% up for it, no one else is going to give a damn. So dance to your own tune and do it your way. Make crafted products you love, create environments you want to hang out in and give the kind of service you’d love to receive yourself.

- Choose a business partner as wisely as you would choose a spouse.

- The power of any brand is inversely proportional to its scope.

- Planning is merely glorified guesswork. Long-term planning is a vain, self-indulgent fantasy. Don’t waste your time.

- Act, don’t plan.

- Constraints are just advantages in disguise and opportunities to be innovative and imaginative. Cherish constraints. Embrace them.

- Be very wary of external agencies and partners. They all speak a good game and promise the earth but at the end of the day they have no reason to care as much as you.

- Living the punk DIY ethic means not relying on existing systems, processes or advisers as this would foster dependence on the system.

- You need to be an independent, an outsider, a nomad, a libertine. You need to be completely self-sufficient and not rely on anyone for anything. If a skill set is important to your business, then you better learn it and learn it fast.

- You need to create pull to be sustainable. And you don’t create pull through sales.

- Everything you do is sales and all of your employees are selling all the time. Act accordingly.

- Pretty much all you need to do for people to hate you is to be successful doing something that you love.

- When you manage to get the Holy Grail of other businesses copying you, whilst others are hating you, you know you have hit a home run.

- Eighty per cent of all new businesses fail. And they always fail for financial reasons. The more you understand the numbers the less likely they are to crush you and your dreams.

- Comfort zones are places where average people do mediocre things. If you are even the tiniest bit comfortable then you need to push harder.

- The lifeblood of your business is cash. If you can’t manage a cash flow, then you can’t run a business.

- Spend every last dime as if it actually was your last and ensure that your team spend every single cent as if it were their own.

- It was about empowering the change-makers, the misfits, the libertines, the community, the frustrated, the independents, the punks. Together we can, and will, change anything.

- There is a huge difference between making a sale and actually being paid for that sale.

- If you price down you down-sell everything, and there’s no going back.

- You need to defend your price point like a junkyard Rottweiler.

- The best way to decide how to allocate your cash and resources is to fully comprehend the opportunity-cost implications of every possible decision you could make in any situation.

- Everything you and your business does is marketing. Modern brands don’t belong to companies, they belong to the customer.

- Anything that you do, anywhere in your business, which is not completely aligned with your mission and your values is like a tiny little suicide.

- Today the only way to build a brand is to live that brand. People want to feel like they are buying into something bigger than themselves. Your brand must give them that opportunity.

- For a stunt to really work then it needs to be intrinsically linked to your mission and you already need to have a really strong following and a credible brand.

- Whatever type of business you are in you need to start building a community and start turning customers into fans.

- The biggest mistake you can make is actually caring what people think. To hell with opinions, conventions and consequences. It is all just a game.

- We hate bad beer so much that we are on a permanent campaign to destroy as much of it as we possibly can.

- Chasing someone else’s perception of cool is one of the stupidest mistakes it is possible to make.

- Having a target market and explicitly marketing to them is a sure-fire way to patronize and alienate pretty much all of the intelligent population.

- There are only three very simple things you need to know about sales.

- Focus on the product.

- Be open and honest.

- Don’t compete on price.

- Sales are merely the by-product of being great elsewhere.

- If you can’t get your staff to fall in love with your business, you haven’t got a chance in hell of a customer to even consider liking it.

- Any great business today is built on these simple yet enduring and all encapsulating pillars. The three pillars are:

- Company culture

- The quality of your core offering

- Gross margin

- Studies show that employees working in a company with a strong company culture are more than twice as effective as employees working in a company with a weak culture.

- The things that apply to your business externally are just as important, if not even more so, inside it.

- People mimic the behavior and beliefs of their leaders so make sure that you, and the people leading your business, live and breathe the behavior you want to perpetuate.

- It isn’t enough for people to know what their business is doing. They have to know why it is doing it.

- Companies need to wise up and max out. Smart companies realize, rather than minimizing wages, it is infinitely more productive and profitable in the long term to look to maximize engagement, loyalty, retention and productivity.

- Culture has to be a priority from the get-go and it has to start with the founders and then flow from the early employees.

- Working on your company culture is actually a much more effective form of marketing than pretty much all traditional marketing mediums combined. Culture is marketing. Culture is brand. Culture now resonates much more with consumers than advertising does.

- We have two simple rules for hiring:

- They have to be as passionate about our mission as we are.

- They have to be the right cultural fit.

- If you want your team to really rumble you’ll need to recognize their efforts. Explicitly and frequently. Leave your heartfelt praise and encouragement ringing in their ears and the impact can be off the charts.

- Unless you add amazing people to your team, you are going to spend a hell of a lot of time trying to get average people to consistently make great decisions.

- Teams tend to operate at, or close to, the ability level of the weakest team member.

- Whatever happens, good, bad or ugly, it is a direct consequence of your leadership.

- Leaders are rare inspirational beings. Managers are ten a penny; the world is full of adequately competent middle managers trapped in corporate hell.

- Work harder, think smarter and focus with laser-like efficiency.

- At BrewDog we have a fifty-fifty rule for our five directors. I and the other four people who lead our business are only allowed to spend half of our time working on the day-to-day operations of the company, on solving current challenges and dealing with existing issues and we have to spend at least half of our time working on ways to improve, grow and develop our business, on ways to drive us towards our next phase of growth.

- Look for inspiration everywhere. The only place you should never look is within your own industry. Screw what all the other clowns are doing. Ignore it, blank it out; it is of no relevance or significance whatsoever.

- Comfort zones are places where average people do mediocre things.

- You will not always get it right. But every time you move, every time you make a bold decision, it will take you one step closer to finding the path you are searching for.

- Your actions will determine your destiny.

- The more action you take, the more opportunities open themselves up to you.

- Your team should be governed by your values and your culture and not by policies and rules.

- Keep the team as well informed as possible so they can buy into the excitement of what the business is both planning and currently achieving, both of which act as a great motivator.

- Put systems in place before, as opposed to after, they are needed and put an infrastructure in place for where you want to be in two years’ time.

- Write down your five biggest problems, sit down in a room with your team, and solve them. Then on to the next five.

- Attitude is the difference between a setback and an adventure.

- So whilst the fools, rats and wannabes are massaging each other’s egos you need to be plotting your revenge. Not on them specifically, but on the system that bred such morons. You need to be quietly planning how to blow the status quo to pieces and create a whole new world order.

- You should always imagine the communication from the other party’s perspective. Put thought into what you say and how you say it.

- Don’t shout too often, so that you can make sure it truly counts when you want to roar.

- It is paramount you track at least ten of the most important performance indicators of your business monthly.

- When it comes to your management accounts you should definitely be tracking sales, cost of sales, overheads, gross margin, EBITDA and net margin. You will also need to monitor items on your balance sheet at regular and short intervals, such as debtors, creditors and, most importantly, your cash position. In addition you should track certain other KPIs (key performance indicators), depending on what is important in your business and your current focus. For instance, you should consider tracking things like: average spend per transaction, staff turnover, customer complaints, referrals, shipment accuracy, sales mix, refunds, wastage, sales growth, additional customers, online engagement or staff happiness (to name but a few). In determining which items you need to keep close tabs on it really depends on your business and your objectives.

- No measurement = no reporting = no visibility = no one cares = your ultimate demise.

- Always do your negotiation homework. Find out about the other party, what makes them tick, their likes and dislikes. Ultimately think about what’s in it for them. Then build your argument around how the deal helps them, because at the end of the day they care much more about what is in their interests than yours.

- Find a solution, structure and deal they feel comfortable with, and positive about. But one that is ultimately engineered around what you want.

- You need to provide the vision, strategy and tools to help your team achieve your goals.

- Whatever goals you’ve set, you should have a list of pint-sized systems, things which you rigorously adhere to without fail, that if consistently applied will help ensure you both achieve your goals and strengthen your brand and company in the long run too.

- Committees are breeding grounds for compromise as the tyranny of conformity rules the roost. Conformity is no place for risk and compromise is no place for innovation.

- Individual vision is always the force behind truly remarkable ideas and concepts.

& Other Stories was an instant hit when it was launched by H&M in 2013. It started out with seven stores – in Barcelona, Berlin, Copenhagen, London, Milan, Paris and Stockholm – and now has over 50 stores in 13 countries.

The brand concept emerged from an internal H&M plan to launch a premium beauty brand. Sara Hildén-Bengtsson, together with colleagues Samuel Fernström, Karin Nordström and Helena Carlberg, pitched an alternative idea to create a beauty, fashion and accessories brand with a creative feel – an atelier that would allow women to curate their own personal style. Prices would sit somewhere between H&M and Cos’s and collections include staple items such as striped t-shirts and silk blouses alongside patterned dresses and trainers from Nike and Adidas.

“Everyone was talking about personal style and street style photography – this is 2010, so Instagram didn’t even exist back then,” says Hildén-Bengtsson. “We went back to our decision makers and said ‘we think we should do something about personal style’.”

The business was hesitant at first. “They said, ‘It looks exactly the same as H&M – you say you’re going to do beauty and shoes and ready to wear and accessories’ and we said ‘we know, but it will be founded in 2013 so believe us, it’s going to be different’. They said, ‘OK, let’s do it’ and that’s how it all got started,” she continues.

“Then we were only five people working with the project and I must say, I think the H&M group was really brave to start new brands and do new developments like this. They dare to do new things. Of course, they have the muscles as well, but I think they’re very exciting in that way.”

Hildén-Bengtsson studied graphic design and advertising at Sweden’s Forsbergs Skola and communications at the Royal College of Art. She joined the H&M group’s special projects team in 2007 after working at Neville Brody Associates and on creative projects for Kenzo and Liberty.

As creative director of the new concept, she worked with a small team to establish the brand’s tone of voice and its visual identity. From the outset, it has always felt more like a boutique label than a global brand owned by one of the world’s biggest retailers. Indeed its creative team operates independently from the H&M group, there is no clue of parentage in the store, and everything from photoshoots to clothing and creative campaigns are conceived in-house. The team occasionally collaborates with external agencies (it worked with Made Thought to create packaging) but oversees all of the brand’s creative output.

“We all talked about the fact that we are happiest when we are in the studio working and that is where everything gets done – from the collections to the packaging for the beauty, all the art direction, photo shoots, everything is happening with the studio and everything is fitting together,” says Hildén-Bengtsson.

“It’s almost like going back to the Royal College in a way with all of the different fields working together … there’s a lot of different disciplines and they all need to work together to make the brand as coherent as possible, and I think that’s the beauty of it. That’s kind of the heart of the whole story [and] the idea of the atelier needed to be reflected within the store. If you go into & Other Stories, it should feel almost like a pop-up shop. It has that creative vibe to it, you have that feeling of, ‘I’ve just been to a creative space’…. The online shop obviously needed to reflect that, so it’s almost like a digital mood board that you go to for inspiration.”

& Other Stories launches a handful of new collections each season. Each collection or ‘story’ is inspired by a different city and showcased in films and photo stories on its website and social channels. The brand regularly launches ‘co-labs’ with creatives and retailers – it has created capsule collections with Rodarte and singer Lykke Li as well as shoe brand Toms and Central Saint Martins graduate Sadie Williams. The choice of collaborators is diverse and often surprising.

“We did a collaboration with Sadie Williams when she was almost straight out of Central Saint Martins – we just thought her degree show was fantastic – so it has been collaborations at all kinds of levels,” says Hildén-Bengtsson.

The brand also aims to continually surprise audiences with its advertising and celebrate individuals with their own distinct style. The lack of diversity remains a major issue in fashion but & Other Stories has been more inclusive than most when it comes to campaigns: for AW15 it launched a campaign starring trans models Hari Nef and Valentijn de Hingh and shot by trans photographer Amos Mac. The following year, it launched a Valentine’s Day campaign featuring a same sex couple and in 2014, teamed up with nonagenarian style icon Iris Apfel.

The brand’s films range from stop-motion shorts to a humorous tale directed by Wendy McColm and starring French model Jeanne Damas. The film pokes fun at the way women are often represented in fashion films with Damas presented as a self-indulgent bohemian. It also teamed up with Lena Dunham to create a short promoting a co-lab by designer Rachel Antonoff.

& Other Stories’ success is based not just on its clothes and unexpected collaborations but the attention to detail that runs through every aspect of the customer experience – from packaging to store design. In store, a pop-up feel is created with concrete floors, exposed lighting and clothes displayed on moveable racks and shelving units. “We have got good feedback from people saying that they felt when they went into the store, you could see there was a lot of love put into everything that was done,” says Hildén-Bengtsson.

The brand’s stripped back website features some lovely imagery and its Instagram feed offers a behind-the-scenes look at the atelier as well as close-ups of store displays and product shots. It also regrams customers’ posts, creating a feed with a personal, intimate feel. It produces bespoke content for different platforms but the same aesthetic and tone of voice runs throughout all of & Other Stories’ communications.

“I think customers don’t always remember or care about if they’ve seen something on Instagram or on Facebook or in a store … they just see that as the brand voice coming out and I just think it’s so important for everything to be as coherent as possible,” says Hildén-Bengtsson.

“That doesn’t mean that everything has to be exactly the same, but it should feel like it’s the same brand and the same voice coming through, so you feel that you trust the brand and you feel love for it or you feel excited about it – that you have some kind of connection to that brand. I hope that’s what we were able to create with & Other Stories.”

After six years at & Other Stories, Hildén-Bengtsson has left the brand to set up a new creative studio, Open. “I love the startup phase. I’m that kind of person that loves creating concepts and new brands,” she says. “I stayed for almost seven years. That’s a long time for someone who has this type of mindset but that’s because I’m totally in love with the brand and all the fantastic people that work with it so for me, I needed to be challenged again, and scared and thrilled and so on.”

As Hildén-Bengtsson notes, the retail experience has changed dramatically in the past few years. Brands are being more creative online – whether through their use of social media or creating more dynamic websites – but now face the challenge of enticing customers into physical stores when it’s often quicker and easier to shop online. The shops that are thriving are those who can offer something extra – whether it’s in-store stylists and beauty bars or florists and cafes. “I think we’re going to see a boom in the whole experience design or communication [design] in stores because they need to find their reason for being,” she says.

Online or off, the key to engaging with consumers is of course, devising compelling experiences that feel genuine and distinctive. “I think you have to be really good at storytelling – telling your story, why you exist on the market, what you are selling and why customers should choose to love this brand instead of another,” says Hildén-Bengtsson.

“There is so much information and so much going on now that people are very clever and they will only connect with things that are real so I think that’s the lesson now – to really tell all the great things that you do with the brand and why you’re doing them and how you do it and be clear in your communications.”

In the beginning, it was “Let’s disrupt the mattress industry. It’s broken.” That quickly morphed into “Let’s invent an industry around sleep” … Co-founder and COO Neil Parikh’s father is a sleep doctor, and he went to a year of medical school. The mattress industry was a mess. You walk into a store expecting a confusing experience, but you don’t expect the 35 models offered to be basically the same product with different labels. It’s worse than buying a used car–at least there you have data points like horsepower, air conditioning, and a Carfax report. But who knows how many springs are good for you?

Parikh retells the story: “After eight months of testing hundreds of mattress types, we learned that people need similar things, like back support, so we decided to make one mattress. Memory foam is super supportive, but it gets hot and it’s not very bouncy, so we added a layer of open-cell latex foam, which keeps you cool and adds just the right bounce. We’re the first company to put memory foam and latex together and have a patent pending.

Luke Sherwin, Casper’s chief creative officer and one of our co-founders, and I lived in a fourth-floor walkup and realized there was no way to get a queen-size bed up our stairs easily. We said, “What if we could compress a mattress to fit into a box the size of a dorm refrigerator?” This way, we can deliver it via UPS so it costs us a 10th of the price to ship. Plus, people can test the mattress in their homes. You have 100 days to try our mattress. If you don’t like it, we’ll come get it for free. Now, a few companies do this, but not long ago most stores required a several-hundred-dollar restocking fee.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MYcYcig7-As

Early on, a couple made a YouTube video about how our bed wasn’t exactly right for them but the experience was amazing. That is the goal. Those customers are still going to talk positively about our company and might even buy our sheets and pillows. Our return rate is low, and we try to donate those mattresses to a local charity, which is more cost-effective than taking them back halfway across the country to refurbish and resell.

People usually buy a mattress about every eight to 10 years. Most companies don’t care who you are–they’ve made their sale. For us, that’s the start of a long-term relationship. Half of our customers talk to someone in-house. The questions are technical, as in “Do I need a box spring?” (No.) “Does it work on this type of bed frame?” (Yes.) We use every conversation to learn something about the customer. We know how long you’ve had your bed, and if you have kids or a pet. We keep track of all that, and then send people anniversary gifts, or dog beds. It’s not about just selling you a bed. It’s “How do I make this person our biggest advocate?”

Casper Labs came from that customer database. We have 15,000 customers who are part of our product-development process. They come to events, and test prototypes. Many are obsessive about sleep. They send us sleep tracker data and say, “I tested this product versus this one, and here’s what I found.” That process has helped us build a group of evangelists.

We consider ourselves a tech company first. We’ve created software that lets us know exactly where our raw materials and mattress components are and how to forecast what and when to build. If the UPS truck is delayed, we can reach out to the customer and say, “Hey, we’ve been tracking your order and noticed something has gone awry.” If you’ve bought a mattress, instead of having to find your order number, our customer-care expert knows who you are without even asking.

By selling directly to customers, we don’t have the same cost structure. We thought about how much we needed to spend on the materials as well as service and returns. There’s a psychological barrier around $1,000, and most people spend $500 on their first bed. We had to be affordable enough so they could feel that they could reach up.

There are many more ways to create an ideal sleep environment. The day after we launched, we started working on pillows and sheets. We questioned how both are produced and then made prototypes. We tried 100 different densities of materials for pillows, including buckwheat, and had customers try many of them. It took 16 months to come up with one pillow that works for everyone. We did a similar process with our sheets and found most people want them to breathe well and last a long time. We’ve been taught to believe that 1,000-thread-count hotel collection sheets are what everyone wants. It turns out, the more threads, the more filler fiber, which means the sheets are going to sleep really hot. Our perfect balance is 90 threads one way, 110 the other. We haven’t decided what the next product is. Customers have asked for everything from lights to sleep trackers. But we do know the category is enormous.

Whole Foods helped shape the healthy-foods movement. We want to do the same for sleep.

While still small, direct-to-consumer mattress startups like Casper are keeping the sleep giants up at night. Mattress Firm, which in November announced it would acquire Sleepy’s, making it the largest U.S. mattress chain, has launched an online bed-in-a-box arm called Dream Bed, and it’s not the only incumbent to pull a copycat move. Given that in 2014 some 35 million people bought mattresses in just the U.S., many potential converts remain.

Momondo’s vision is of a world where our differences are a source of inspiration and development, not intolerance and prejudice. Its purpose is to give courage and encourage each one of us to stay curious and be open-minded so we can all enjoy a better, more diversified world.

To do this, the search engine has focused on rich, inspiring, human content. Telling great stories of people and their adventures across the world, inspiring people to “stay curious”, to explore and go further. In 2016, this content became remarkable with a project exploring how connected we all are to the world. At a time of social polarisation across the world, it reminded people that we are all citizens of the world.

The “DNA Journey” video campaign has been viewed more than 28 million times on their Facebook page, viewed more than five million times on their YouTube channel, shared more than 600,000 times globally and commented on by thousands of people from all over the world. 169,631 people entered our The DNA Journey competition with the hope of winning their very own DNA Journey (the competition is now closed).

What is the purpose of The DNA Journey?

The purpose of The DNA Journey campaign is to show that we, as people, have more things uniting us than dividing us. The DNA Journey is part of momondo’s overall vision of a more open and tolerant world. You can read more about momondo’s vision and ongoing activities here: letsopenourworld.com.

How were the participants found?

As is the case with many campaign films, we employed casting agencies to help us find participants. Specifically, we used two agencies. These two agencies sourced participants via their extras databases, their own networks and via online forums. In the process of selecting the participants, momondo was presented with their ethnicity and family history only.

The casting agencies filmed 67 people talking about themselves and where they come from for 10 minutes each. After this, they were asked to take a saliva DNA test. Based on these results, together with the participants’ personal stories, we selected 16 for the shoot in Copenhagen. The criteria we looked at were their ancestry, their perception of themselves and the world, and if there was a surprise element in their DNA results.

Are there actors in the video?

The participants of The DNA Journey appear in their own name and receive their own DNA results. Neither their occupation nor their educational background had any bearing upon their selection.

Participants came from all walks of life and all kinds of occupations. Examples of the participants’ occupations are: secretary, dog trainer, actor, account manager and model. We did not carry out specific research into what kind of profession the participants had – or have had – as they would be appearing as themselves.

However, because of the great interest in the participants’ possible acting experience, we have since investigated how many have more or less experience acting or appearing as extras before. This applies to 10 of the participants. The only professional actress purposely cast was the role of the female interviewer. The background audience was bolstered with extras whom we did not DNA test.

Were the film’s participants told how to react to their DNA tests?

The participants in the film were not cast to act, and what they say in the film are their own words and thoughts. They were interviewed about their personal relationship to their ancestry and nationality, and later shown the result of the DNA analysis that was made a few weeks earlier.

Before the reveal of the DNA results, the contestants were very excited about their results and we talked with them about the fact that they were welcome to express this in the film. The participants were not directed individually in how to react or what to say about their DNA results.

Did the participants receive payment for their appearance?

As is normal practice in the production of an advertisement, participants were paid for both their appearance and rights.

How was the advertisement shot?

The campaign film was shot in a music venue, Vega, in Copenhagen from April 6th to April 8th 2016. While an intertitle in the film states, “Two weeks later”, all of the participants carried out their DNA test before the shoot. This is a modification we made for the sake of storytelling. Similarly, the spitting scenes were shot when the entire crew was together in Copenhagen for logistical reasons. During the shoot, participants were first interviewed about their views on their own nationality and other nations, and then presented with the results of their DNA test.

Were there any retakes in the film?

Yes. When a campaign film is shot, there can be multiple reasons for retakes, such as problems with the sound, an unclear image, people mumbling or the lighting being wrong. The important thing for us was to capture the spontaneous reactions when participants saw their DNA results for the first time. The participants only opened the envelope once and the film contains the reactions from that take. This is also why we used four cameras to ensure that we captured the reaction on film.

Is the story about two participants being related real?

Yes, the story is real and they were both overwhelmed when they found each other. We think it is a good story and they both shared it with their families after the shoot. The two participants are distant cousins. When you test your DNA with AncestryDNA, our partner for this campaign, you can check whether or not there are any distant cousins registered in AncestryDNA’s database. It was a pure coincidence that two out of the 67 people tested were related.

Who conducted the DNA tests in the film?

AncestryDNA carried out the tests. In the test you learn about your DNA based on 26 regions worldwide. AncestryDNA gives ethnicity estimates that map back to broad geographical regions, often including one or more countries.

AncestryDNA was able to provide each participant with a more detailed DNA map than the average taker of their DNA test, because the participant selection process had provided them with a greater understanding of each participant’s family history, surname and ancestral background.

How have the participants felt since the film was shot?

Many people have asked what reactions the participants have had since the shoot. Here are three participants’ testimonials.

‘Thank you so much for the amazing opportunity to be a part of your project. It was one of the most incredible experiences of my life. I am so grateful to have lived that experience, grateful for the way it changed me and how it is shaping my work as an artist today. Grateful for the journey into myself and for seeing others uncovering their beautiful journeys while carrying a bit of my own. I feel invincible, ageless and ready to face what the future holds.’

‘It was a profoundly emotional experience, and made me question who I am and who I thought I was. My family and friends were inspired by my journey, and loved the idea behind the campaign! Many of them are now desperate to undergo their own tests to discover their origins.’

‘I feel eager, impatient, excited, motivated, grateful, surprised, overwhelmed and filled with beautiful energy after the experience we’ve lived together in the studio.’

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G84LJ5wkYJo

The minibus crosses the vast plateau on a newly paved road. Cracked fields stretch away towards the Moroccan desert to the south. Yet the barren landscape is no longer quite as desolate as it once was. This year it became home to one of the world’s biggest solar power plants.

Hundreds of curved mirrors, each as big as a bus, are ranked in rows covering 1,400,000 sq m (15m sq ft) of desert, an area the size of 200 football fields. The massive complex sits on a sun-blasted site at the foot of the High Atlas mountains, 10km (6 miles) from Ouarzazate – a city nicknamed the door to the desert. With around 330 days of sunshine a year, it’s an ideal location.

As well as meeting domestic needs, Morocco hopes one day to export solar energy to Europe. This is a plant that could help define Africa’s – and the world’s – energy future.

Of course, on the day I visit the sky is covered in clouds. “No electricity will be produced today,“ says Rachid Bayed at the Moroccan Agency for Solar Energy (Masen), which is responsible for implementing the flagship project.

An occasional off day is not a concern, however. After many years of false starts, solar power is coming of age as countries in the sun finally embrace their most abundant source of clean energy. The Moroccan site is one of several across Africa and similar plants are being built in the Middle East – in Jordan, Dubai and Saudi Arabia. The falling cost of solar power has made it a viable alternative to oil even in the most oil-rich parts of the world.

Noor 1, the first phase of the Moroccan plant, has already surpassed expectations in terms of the amount of energy it has produced. It is an encouraging result in line with Morocco’s goal to reduce its fossil fuel bill by focusing on renewables while still meeting growing energy needs that are increasing by about 7% per year. Morocco’s stable government and economy has helped it secure funding: the European Union contributed 60% of the cost for the Ouarzazate project, for example.

The country plans to generate 14% of its energy from solar by 2020 and by adding other renewable sources like wind and water into the mix, it is aiming to produce 52% of its own energy by 2030. This puts Morocco more or less in line with countries like the UK, which wants to generate 30% of its electricity from renewables by the end of the decade, and the US, where President Obama set a target of 20% by 2030. (Trump has threatened to dump renewables, but his actions may not have a huge impact. Many policies are controlled by individual states and big companies have already started to switch to cleaner and cheaper alternatives.)

Due to the lack sun on the day I visit, the hundreds of mirrors stand still and silent. The team keeps a close eye on weather forecasts to predict output for the following day, allowing other sources of energy to take over when it is overcast.

But normally the reflectors can be heard as they move together to follow the Sun like a giant field of sunflowers. The mirrors focus the Sun’s energy onto a synthetic oil that flows through a network of pipes. Reaching temperatures up to 350C (662F), the hot oil is used to produce high-pressure water vapour that drives a turbine-powered generator. “It’s the same classic process used with fossil fuels, except that we are using the Sun’s heat as the source,” says Bayed.

The plant keeps generating energy after sunset, when electricity demands peak. Some of the day’s energy is stored in reservoirs of superhot molten salts made of sodium and potassium nitrates, which keeps production going for up to three hours. In the next phase of the plant, production will continue for up to eight hours after sunset.

As well as boosting Morocco’s power production, the Ouarzazate project is helping the local economy. Around 2,000 workers were hired during the initial two years of construction, many of them Moroccan. Roads built to provide access to the plant have also connected nearby villages, helping children get to school. Water brought in for the site has been piped beyond the complex, hooking up 33 villages to the water grid.

Masen has also helped farmers in the area by teaching them sustainable practices. Heading towards the mountains, I visit the Berber village of Asseghmou, 30 miles (48 kilometres) north of Ouarzazate, where a small farm has now changed the way it raises ewes. Most farmers here rely on their intuition alone but they are being introduced to more reliable techniques -such as simply separating animals in their pens – which are improving yields. Masen also provided 25 farms with sheep for breeding purposes. “I now have better food security,” says Chaoui, who runs a local farm. And his almond tree is thriving thanks to cultivation tips.

Even so, some locals have concerns. Abdellatif, who lives in the city of Zagora about 75 miles (120 kilometres) further south, where there are high rates of unemployment, thinks that the plant should focus on creating permanent jobs. He has friends who were hired to work there but they were only on contract for a few months. Once fully operational, the station will only require about 50 to 100 employees so the job boom may end. “The components of the plant are manufactured abroad but it would be better to produce them locally to generate ongoing work for residents,” he says.

A bigger issue is that the solar plant draws a massive amount of water for cleaning and cooling from the local El Mansour Eddahbi dam. In recent years, water scarcity has been a problem in the semi-desert region and there are water cuts. Agricultural land further south in the Draa valley depends on water from the dam, which is occasionally released into the otherwise-dry river. But Mustapha Sellam, the site manager, claims that the water used by the complex amounts to 0.5% of the dam’s supply, which is negligible compared to its capacity.

Still, the plant’s consumption is enough to make a difference to struggling farmers. So the plant is making improvements to reduce the amount of water it uses. Instead of relying on water to clean the mirrors, pressurised air is used. And whereas Noor 1 uses water to cool the steam produced by the generators, so that it can be turned back into water and reused to produce more electricity, a dry cooling system that uses air will be installed.

These new sections of the plant are currently being built. Noor 2 will be similar to the first phase, but Noor 3 will experiment with a different design. Instead of ranks of mirrors it will capture and store the Sun’s energy with a single large tower, which is thought to be more efficient.

Seven thousand flat mirrors surrounding the tower will all track and reflect the sun’s rays towards a receiver at the top, requiring much less space than existing arrangement of mirrors. Molten salts filling the interior of the tower will capture and store heat directly, doing away with the need for hot oil.

Similar systems are already used in South Africa, Spain and a few sites in the US, such as California’s Mojave desert and Nevada. But at 86ft (26m) tall, Ouarzazate’s recently erected structure is the highest of its kind in the world.

Other plants in Morocco are already underway. Next year construction will begin at two sites in the south-west, near Laayoune and Boujdour, with plants near Tata and Midelt to follow.

The success of these plants in Morocco – and those in South Africa – may encourage other African countries to turn to solar power. South Africa is already one of the world’s top 10 producers of solar power and Rwanda is home to east Africa’s first solar plant, which opened in 2014. Large plants are being planned for Ghana and Uganda.

Africa’s sunshine could eventually make the continent a supplier of energy to the rest of the world. Sellam has high hopes for Noor. “Our main goal is to become energy-independent but if one day we are producing a surplus we could supply other countries too,” he says. Imagine recharging your electric car in Berlin with electricity produced in Morocco.

With the clouds set to lift in Ouarzazate, Africa is busy planning for a sunny day.

Warby Parker is a lifestyle brand with the goal to offer designer eyewear at a revolutionary price while leading the way for socially conscious businesses. By engaging directly with consumers, they’re able to offer ultra-high-quality, vintage-inspired frames for $95 including prescription lenses and shipping. Social innovation is woven into the DNA of our company, and for every pair of glasses purchased, a pair is distributed to someone in need. In 2015, Fast Company named them the #1 Most Innovative Company. We’re also a certified B Corporation, which means that we are held to the highest standards of social and environmental performance.

The brand story continues … “It turns out there was a simple explanation. The eyewear industry is dominated by a single company that has been able to keep prices artificially high while reaping huge profits from consumers who have no other options. We started Warby Parker to create an alternative. By circumventing traditional channels, designing glasses in-house, and engaging with customers directly, we’re able to provide higher-quality, better-looking prescription eyewear at a fraction of the going price.

We believe that buying glasses should be easy and fun. It should leave you happy and good-looking, with money in your pocket. We also believe that everyone has the right to see. Almost one billion people worldwide lack access to glasses, which means that 15% of the world’s population cannot effectively learn or work. To help address this problem, Warby Parker partners with non-profits like VisionSpring to ensure that for every pair of glasses sold, a pair is distributed to someone in need. There’s nothing complicated about it. Good eyewear, good outcome.”

Extract from a recent Forbes article:

Warby Parker was founded in 2010, by four friends, Neil Blumenthal, Dave Gilboa, Andy Hunt and Jeff Raider, who happened to be in business school.

The inception of the idea had taken place in a computer lab, as the four friends lamented the state of the eyeglass industry. Why are glasses so expensive?

The first Eureka moment came when investigating that very question. Dave describes: “Understanding that the same company owned LensCrafters and Pearle Vision, Ray-Ban and Oakley, and the licenses for Chanel or Prada prescription frames and sunglasses — all of a sudden, it made sense to me why glasses were so expensive.”

And with that epiphany, the idea began to take shape and the business model was born. They would create a vertically integrated company. Neil explains, “It was really about bypassing retailers, bypassing the middlemen that would mark up lenses 3-5x what they cost, so we could just transfer all of that cost directly to consumers and save them money.”

If you think that’s a mouthful, that’s just the beginning: “When you buy a Ralp Lauren -0.42% or Chanel pair of glasses, it’s actually a company called Luxottica that’s designing them and paying a licensing fee between 10 and 15% to that brand to slap that logo on there. If we did our own brand, we could give that 10-15% back to customers.”

Even with all this thought out, it still wasn’t clear what would come of the idea. As Dave Gilboa, Warby Parker’s future co-CEO, put it: “Warby Parker wasn’t the basket that I wanted to put all my eggs into.” And Neil Blumenthal, the other future co-CEO, felt no differently: “In some respects, my time in business school, I was sort of hedging my bets between 1) Would be Warby Parker take off in the startup world, or 2) Would I have an offer after [graduation.]”

After incubating the idea for a year and a half, the idea finally hatched. The launch was so successful that the team hit their first year sales targets in the first three weeks. That’s like expecting one child and instead landing with triplets.

The biggest benefit of good branding is, of course, brand loyalty. Ries writes in Positioning: “History shows that the first brand into the brain, on the average, gets twice the long-term market share of the No. 2 brand and twice again as much as the No. 3 brand.”

But being first in the brain is still only the first step. “You build brand loyalty […] the same way you build mate loyalty in a marriage. You get there first and then be careful not to give them a reason to switch.”

Soon after Warby Parker’s success, copy-cats began cropping up. But what none of these copy-cats understood was Warby Parker already occupied the No. 1 spot in the customer’s mind, and to date, had done everything in their power to keep those customers. Al Ries explains this phenomenon: “Moving up the ladder in the mind can be extremely difficult if the brands above have a strong foothold and no leverage or positioning strategy is applied.”

“What dethrones a leader, of course, is change.” As Al Ries points out, “To play the game successfully, you must make decisions on what your company will be doing not next month or next year but in 5 years, 10 years.”

The question: Can Warby Parker keep its lead?

“We’re often asked why Warby has been successful. If we sum it up in one word, it’s deliberate,” Dave says. Their passion for the idea has helped drive that meticulous mindset.

But contrary to popular belief, working harder is not what leads to success. As Al Ries writes, “The only sure way to success is to find yourself a horse to ride. It may be difficult for the ego to accept, but success in life is based more on what others can do for you than on what you can do for yourself.”

Warby Parker has built its brand to build relationships. It allows them to build meaningful relationships because it’s a brand that cares. It cares about the world, it cares about its people and it cares about its customers.

So much of success is serendipitous. And the key to serendipity is increasing the chances for a serendipitous encounter. The more relationships you build, the odds swing in your favor that that one of those relationships will help you succeed down the line that one time you need it.

Tim Riley explains Warby Parker’s marketing tactics

Here is an interesting talk by Tim Riley who heads up the online experience at Warby Parker. His job is to make the process of buying glasses online as fun and easy as possible:

Here are 7 things to take away from Tim’s talk, which is also transcribed below:

- Make Me Care … Start by putting together a fundamentally great story. Warby Parker got tremendous word-of-mouth from the get-go because their story resonated with the press, who were eager to tell their readers about it. This should work for all brands, but it should be especially powerful for lifestyle brands. (Read: It was a dark and stormy night… – 11 Examples of Storytelling in Marketing)

- Understand your brand hierarchy … What’s most critical? Warby Parker lays out its brand in a linear fashion: Lifestyle brand -> Value and Service -> Social Mission. Rather than trying to do everything at once, they focused on the most important fundamentals that would enable them to do what they really wanted to do. (Read: 30 Tips To Build Your Personal Brand From 37 Experts [Infographic])

- Steal the show! … Get your early buzz + influencer buy-in by being tastefully rebellious. Warby Parker wanted to be a part of NY Fashion Week in Fall 2011, but couldn’t afford to get involved the traditional way- so they invited 40+ editors to a ‘secret event’ at the NY Public Library. They earned buzz (without paying for it!) by creating a remarkable experience. (Read: Guerrilla Marketing Tactics Every Startup Should Know: 8 Case Studies and Examples)

- If It Ain’t Fun, Why Do It … Create content that’s legitimately fun. Warby Parker’s annual reports include things like what bagels they ate, or what were the most popular misspellings of the brand. In 2012, this led to their 3 highest consecutive sales days of the year. (Warby Barker became a standalone April Fool’s site, which got 2.5x the traffic of the actual site.) If you’re not enjoying your own content, why would anybody else?

- Figure out ways to turn mundane interactions with your brand into remarkable, social ones. Warby Parker’s team responded to questions on Twitter with quickly-shot YouTube videos, which average 120 views per video. They also provided a make-a-snowman kit with their gift cards, and added a #WarbySnowman hashtag– turning it into a fun, remarkable experience. (Read: 17 Ways That 15 Companies Got Massive Word-of-Mouth By Delighting Their Customers)

- Better Together … Partnerships make tonnes of sense for lifestyle brands. Warby Parker does partnerships with all sorts of other brands and entities. Ghostly International (music label), Man Of Steel movie (Clarke Kent as the original do-gooder and most famous glasses-wearer), DonorsChoose.org, (in line with social mission, $30 gift card allows customers to get more directly involved with projects). (Read: Examples Of Collaboration In Ecommerce – Win-Wins For Everybody)

- Create unique, memorable physical experiences. Warby Parker makes very interesting decisions: The flagship store looks like a library, and the eye exams are done with old-school railroad flipping things. When they wanted to do mobile showcases, they used bicycles, and then a repurposed schoolbus. Their first showcase had a Yurt in it. Every time they had a chance, they chose to do something unorthodox.

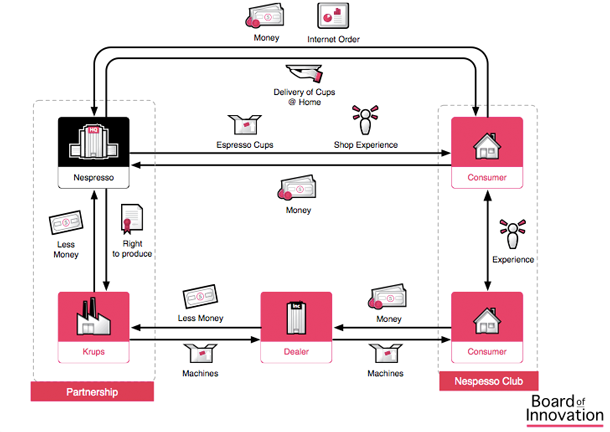

“Nespresso. What else?” ask George Clooney, as if you were to question his taste in coffee. In 1976, Eric Favre of Switzerland’s largest business, Nestle, invented the Nespresso system. 10 years later, Nestle remembered that it was the coffee that people really wanted, not just a great machine. It licensed out manufacturing of the hardware and created “Le Club”.

Whilst the machines are now made by others, from Alessi to Krups, the coffee is made by Nestle, with drinkers subscribing to pod refills sent directly to their homes. Over the decades, coffee culture came to dominate our towns, and people demanded better at home. Nestle, as Nespresso, was waiting.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f5QdLFip8iU&list=PLQ2eIUsAVWUyoz0kY_nbMg3xUjYBjqrxF&index=3

Nespresso’s success lies in two factors – its business model, and its market strategy. The low cost machines and premium coffee is an echo of the “shaver and blades” model used so successfully by Gillette, whilst the direct to consumer channel allows the brand to build a deep understanding and relationship with its drinkers.

Nestle targeted two primary markets for growth – USA and China. However it realised it would need different strategies from what had worked in Europe. In the USA, Nespresso sought to differentiate itself by targeting women, with a more sophisticated approach, endorsed by Penelope Cruz. In China, growth is slower, taking time for people to consider the alternative to tea. Slow, but huge potential. But Nestle is playing a long-term game. “Relax, it will happen” as Clooney might say.

Read the Nespresso history: simple idea to brand experience

A snowboarder glides up-side down over a forest of trees and sticks his hand out to brush the top of a tall pine. He does it so casually, whilst a high-speed camera catches the treetop moment, just another glimpse of Red Bull action. In fact you might be forgetting that Red Bull is actually a drink. The logo is everywhere at these events, but the brand is more than an energy drink.

“Red Bull gives you wings” says the slogan, emblazoned across the sky by stunt aircraft taking part in the brand’s Air Race in front of millions of spectators crowded along the banks of the Danube in Budapest. It’s the same message at the Flugtag, when homemade aircraft take flight and flop just a quickly, of the Cliff diving, from the tall buildings into Boston Harbor, or the Soapbox race, when rickety go-karts hurtle down a mountain side. It’s all pure adrenalin, and fabulous entertainment.

In 1987 Dietrich Mateschitz was in Bangkok selling photocopiers. After a long flight he collapsed into the chair of a hotel bar. “I know exactly what you need, Sir” proposed the Thai waitress. She quickly returned with a glass of Krating Daeng (daeng means red, krating is a guar, or very large bison). Whilst the original ingredients were said to contain bull’s testicles, Mateschitz was soon energising, returning to his native Austria with a plan to modify the recipe, and launch his new brand.

Having sold 6 billion cans, the world’s largest energy drink is often called “liquid cocaine”. But the focus is not the ingredients, it’s the possibilities of the brand – how it makes you feel, not what it is. This is where the high adrenalin sports come in. Red Bull Media House makes the movies of each event, on a budget of around $2 million, but sells the movies for much more. There are a regular NBC reality TV shows featuring its stars, online communities, and Red Bulletin magazine. In fact such content is as important as the product in building the brand, so much so that Mateschitz now calls Red Bull a media company.

“At WeWork, we are committed to creating a world where people can do what they love, where they can create a life’s work and not just a living,” said Adam Neumann, WeWork’s co-founder and CEO.

WeWork began as a simple co-working space for artists, entrepreneurs, and freelancers. It has rapidly expanded to more than 150 locations in 15 countries worldwide. In 2016, the business raised $690 million at a valuation of nearly $17 billion. It charges members a subscription fee.

“When we started WeWork in 2010, we wanted to build more than beautiful, shared office spaces. We wanted to build a community. A place you join as an individual, ‘me’, but where you become part of a greater ‘we’. A place where we’re redefining success measured by personal fulfillment, not just the bottom line. Community is our catalyst.” says Neumann.

WeWork’s workspace design features private offices (for teams of 1–100+) with glass walls to maintain privacy without sacrificing transparency or natural light. Common spaces have a distinct aesthetic and vibe that will inspire your team, as well as the guests you bring into our buildings.

Typical features of a workspace include

- Super-fast Internet. Hard-wired (Ethernet) connections as well as access to Wi-Fi in all WeWork locations.

- Spacious, Unique Common Areas. WeWork spaces includes desks, chairs, desk lamps, and lockable filing cabinets.

- Business-Class Printers. Each WeWork floor has at least one multi-function copier/scanner/printer.

- Free Refreshments. Get free micro-roasted coffee, tea, fruit water, and beer at every WeWork location.

- Onsite Staff, and managers available from 9am-5pm, Mon-Fri.

- Private Phone Booths. Phone booths are available on all floors for private calls.

Events are an essential part of the WeWork experience. From regularly scheduled office hours with venture capitalists or other industry professionals, to tequila tasting happy hours with the whole community, we know how to work, and we know how to have fun. There are events, both social and professional, happening every day to help you build and maintain a strong team culture.

Here is an extract from a Forbes magazine profile:

Mort Zuckerman, the 77 year old billionaire chairman of Boston Properties, controls $19.6 billion (market cap) worth of prime office buildings in cities like New York, Washington and San Francisco, and in June 2013 he took a walk through a little real estate business called WeWork that Adam Neumann and his partner, Miguel McKelvey, were building.

Neumann, then a 34-year-old former Israeli naval officer with a thick mane of black hair, met Zuckerman at the elevator of his second WeWork office in New York’s SoHo neighborhood. “Surprise, surprise–another upstart wanted in on the office rental game,” Zuckerman remembers thinking to himself. Neumann explained the business model: WeWork takes out a cut-rate lease on a floor or two of an office building, chops it up into smaller parcels and then charges monthly memberships to startups and small companies that want to work cheek-by-jowl with each other.

Neumann led Zuckerman past WeWork’s 38,000-square-foot warren of small, glassed-in offices packed with young creative-economy types, the coffee lounge that converts into a beer-and-wine event space during happy hour, the conference rooms brimming with videoconferencing gear and the office managers smiling and taking care of package deliveries and replenishing the free coffee and laser printers. “We’ve got a waiting list months long,” Neumann told him. And the buzz in the air was going to be repeated across seven cities in a dozen new locations before 2015.

Zuckerman warmed up. Here were dozens of members with needs very different from the tenants who sign leases at Boston Properties buildings on Park Avenue. These startups need each other. They feed off each other. They want to belong to something. “Adam understood in a very serious way that we are in a new culture,” Zuckerman says. “I found it extraordinarily creative and original after being in this business for God knows how many years.” (actually, it’s around 50 years!)

Zuckerman asked Neumann to lunch. Then another. By their fourth meeting he made Neumann promise to let him invest personally in WeWork the next time it raised money. And in 2015, almost two years since that first tour, a 200,000-square-foot WeWork will be the anchor tenant of the $300 million redevelopment co-owned by Boston Properties in the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Plans are afoot for another partnership in San Francisco and perhaps Boston down the road.

WeWork’s founders have been content to stay quiet about their story until now, swearing investors to secrecy. No longer. Over the next 12 months the company expects to triple its membership from 14,000 to 46,000 and expand to 60 locations from 21 today and 9 just a year ago. WeWork’s first location four years ago was just 3,000 square feet in SoHo with creaky floorboards and walls power-washed by its founders. Now WeWork is the fastest-growing lessee of new office space in New York and next year will become the fastest-growing lessee of new space in America as it spreads to cities such as Austin and Chicago, not to mention London, Amsterdam and Tel Aviv.

WeWork will gross an estimated $150 million this year with operating margins of 30%. Current plans will push revenue to more than $400 million next year. In February JPMorgan led a massive (and secret) $150 million investment in the company along with the Harvard Corp., Zuckerman and Benchmark. The deal valued WeWork at $1.5 billion. The founders suspect they will be out raising another round next year that could easily fetch a valuation north of $6 billion. If that comes to fruition, Neumann and McKelvey, who each own an estimated 20%, would be paper billionaires.

WeWork is the leader, by far, in a surging co-working space movement. Some 5,900 shared office operations dot the globe today, compared with 300 five years ago, according to Deskmag.com, a site dedicated to tracking co-working trends. Back then there were fewer than 10,000 people working in such locations worldwide. Today that number is closer to 260,000. Niches have begun appearing: Grind caters to repeat founders and veteran professionals. Hera Hub runs three locations in California just for female entrepreneurs. “People want less stodgy offices,” says Julien Smith, CEO of Breather, a startup that takes flexible space to its extreme, offering private office rentals by the hour to members constantly on the go.

WeWork members freely acknowledge the space is scandalously priced per square foot: $350 a month for a desk and $650 per person for 64 square feet per office. But when WeWork opened its latest building in London’s South End, it was 80% full at launch and like the rest will be at near capacity in just a couple months. That’s because members can save hundreds per month when you factor in included services such as security, reception, broadband, printing–and fewer headaches.

But the real perk is having other people around. WeWorkers network at weekly bagel-and-mimosa parties, where they might find a software developer to produce an app for them. Members pitch their ideas at informal demo days and get free advice during office hours from willing outside partners like ad agency Wieden+Kennedy. Handshake agreements and job referrals are made over the wagging tails of members’ dogs.

“Other offices are just depressing compared to here,” says Nicole Halmi of Neon, an image-selection platform in the WeWork Tenderloin location in San Francisco. “The old model of office space is dead,” adds startup veteran Gary Mendel, who runs Yopine from a WeWork in the renovated Wonder Bread factory in Washington, D.C.

City governments are all-in on the benefits that such spaces can bring to the local economy. In San Francisco Mayor Ed Lee rerouted police patrols and opened a precinct outpost in the ragged Tenderloin district to keep the WeWork members there safe. Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel insisted on personally showing Neumann his unannounced plans for new bike paths and other startup-friendly projects to convince WeWork to move to the West Loop. New Boston Mayor Martin J. Walsh chose the new WeWork as the location for one of his first public speeches after taking office. “This is somewhat new to Boston, the innovation economy, but as more and more people see the type of idea of WeWork, more people will get interested in starting companies,” says Walsh.

“WeWork plays both sides of the coin,” says James B. Lee, Jr., the famed investor and JPMorgan Chase vice chairman who has guided the public offerings of Facebook, Alibaba and General Motors. “Institutions have space that young entrepreneurs could use, but they want to start their own business and cut their own trail. WeWork gives them a home and says, ‘We want you here, we will help you and build you.’ ”

Neumann and McKelvey, who still interview every new employee to make sure they don’t see WeWork as just another real estate play, come by their fanaticism for the power of “we” honestly. The two grew up thousands of miles apart but in their own types of communes and without fathers around. Neumann grew up the son of an Israeli single-mother doctor. He spent two early years learning English when his mom was a resident at an Indianapolis hospital. They returned to Israel and moved into the Kibbutz Nirim near the Gaza Strip. All the children lived together in their own dorm, apart from the parents. He and his little sister, Adi, learned community the hard way, as the tribal kids of the kibbutz shunned Neumann’s family for months. “That was the hardest group I ever had to enter in my life,” he says.

Severely dyslexic and an indifferent student, Neumann found acceptance as an expert windsurfer and ringleader for unapproved extracurricular activities. When it came time for mandatory military service, Neumann says he was among the slowest of the thousands of candidates for the elite naval officers’ school, many of whom had trained for their tryout camp for weeks. When the team-building missions came around, Neumann began to take charge. His was one of the last names to be called when the navy picked its 600-member class. He finished third and left the navy after five years of service.

McKelvey grew up one of six kids in a five-mother collective in Eugene, Ore. They were happy and lived simply on gardening and food stamps. Tang, with its forbidden artificial chemicals, was a special Christmas treat. “Looking back, we grew up poor, but living it then we never knew,” says McKelvey’s commune “sister” Chia O’Keefe, an early WeWork’s employee and now head of innovation.

McKelvey was a talented student, but school bored him easily. What he loved was thinking about ways to revive all the empty storefronts and closed buildings in his depressed hometown. His favorite was Lazar’s Bazar, an ugly duckling that stayed open selling a hodgepodge of items as neighbors came and went. McKelvey saved pocket change for weeks to finally buy a $7 silk skinny tie. “It was the 1980s,” he shrugs today.

After playing basketball at the University of Oregon (and earning his architecture degree), he jumped into the 1990s dot-com boom, starting a website that connected Japanese and English pen pals. Eventually he landed a job with an architecture firm in Brooklyn.