- Sales will be largely programmatic, and the process will be automated.

- Salespeople will still be needed but mostly for B2B and large accounts where it becomes essential to understand the human customers who are ultimately responsible for purchases.

- Sales will need to study machine behavior, looking for patterns that could inform their sales strategy.

Brunello Cucinelli, known as the King of Cashmere, runs his Italian luxury design house in fascinating way.

The Italian fashion designer and the founder of the luxury cashmere brand that bears his name. Born on September 3, 1953, in Castel Rigone, Italy, Cucinelli is renowned for his elegant and sophisticated designs, particularly in the realm of knitwear.

What sets Cucinelli apart is not just his focus on high-quality materials and craftsmanship but also his commitment to ethical and sustainable business practices. He’s often referred to as the “philosopher of cashmere” because of his unique approach to blending business success with humanistic values. His company, Brunello Cucinelli S.p.A., is known for creating luxurious and timeless pieces, with a strong emphasis on using natural fibers.

Cucinelli founded his company in 1978 in the medieval hamlet of Solomeo, Italy. Today, the brand is internationally recognized and has expanded beyond cashmere to include a range of clothing and accessories. His designs are often characterized by neutral tones, fine tailoring, and a sense of relaxed sophistication.

Beyond the fashion world, Cucinelli is known for his philanthropy and dedication to social responsibility. He has invested in restoring the village of Solomeo, turning it into a hub of art, culture, and craftsmanship. His holistic approach to business, blending elegance with ethics, has garnered him respect and admiration in the fashion industry and beyond.

Luxury is independent of time: In his first shareholder letter published in English, Brunello talks about the luxury pyramid, and its positioning:

The 8-to-6 Rule: The first example of the unique corporate culture is the very strict working hours. No work related emails or phone calls can be done after 6 o’clock, and 90-minute lunch breaks are obligatory:

Company Guardianship: Brunello is the majority shareholder, and the main reason he took the company public in 2012 was to make sure that it would survive for the next 50 or 100 years:

The +20% System: BC pays their workers, on average, 20% more than other companies to retain world-class talent and ensure them good living standards:

The company is also very careful with growth, and speak a lot about the importance of “not being too widely distributed” as an absolute luxury brand:

Although, despite this careful growth framework, BC has grown its revenue and EBIT at ~500% and 1100% respectively since 2009

Brunello uses his personal wealth as well as part of the company’s profits to give back to society. A good example of this is his School of Craftsmanship which he started back in 2013, located in the small Italian hamlet of Solomeo:

Humanistic Capitalism: In every letter, Brunello is preaching about his business philosophy of combining ethics, quality and dignity. Here’s from 2016:

The Honourable Merchant: in 2017, hegot the Global Economy Prize from Kiel Institute for this exact philosophy:

Focus on what you can change: A very nice excerpt from the 2021 shareholder letter:

Here’s another example of Brunello’s long-term thinking and his commitment to society. He calls it a “1000-year project” – the Universal Library of Solomeo (aka “the Hamlet of Cashmere and Harmony”):

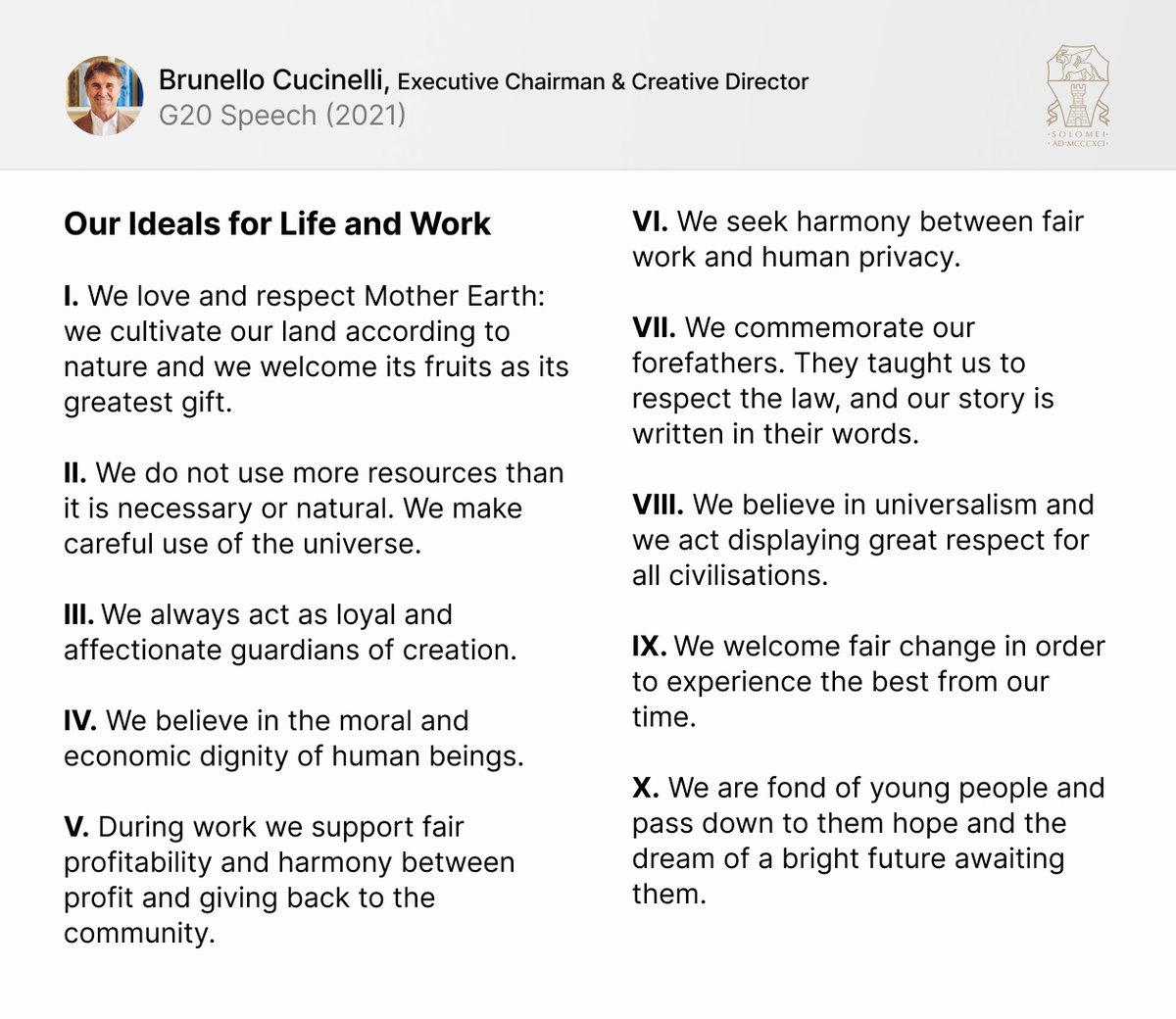

In 2021, Brunello was invited to speak at the G20 meeting thanks to his Humanistic Capitalism philosophy. There, he outlined the company’s Ten Ideals for Life and Work:

Read his book “The Dream of Solomeo”, a must read if you want to understand Brunello’s journey and philosophy.

Everyone is familiar with Mark Zuckerberg’s iconic grey t-shirts, but did you know that they are custom made by BC and cost around $300?

Walt Disney was never satisfied with making movies.

To him, the idea of a theme park gave so much more scope to add value, to be more relevant and engaging with your audience, and to keep the experience alive.

“A picture is a thing that once you wrap it up and turn it over to Technicolor, you’re through. Snow White is a dead issue with me” he said.

“I wanted something live, something that it could grow, something I could keep PLUSSING with ideas. The park is that. Not only can I add things, but even the trees will keep groving. The thing will get more beautiful every year. I can’t change that picture, so that’s why I wanted that park.”

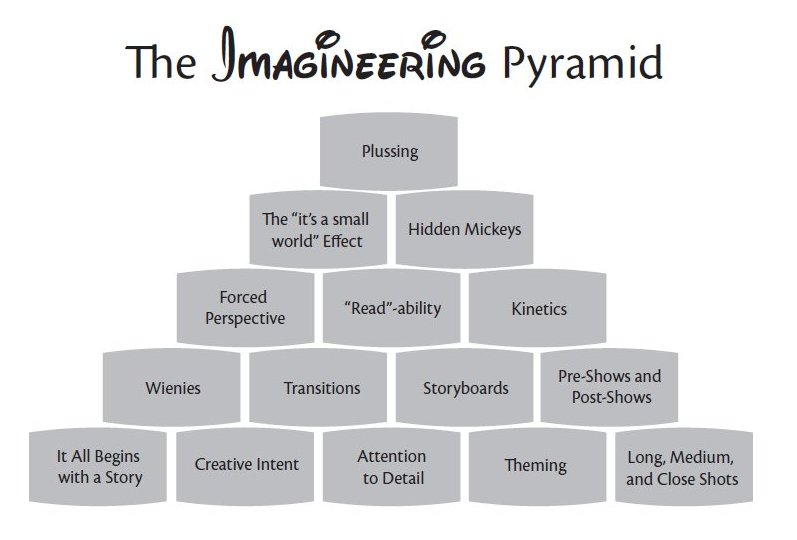

Disney created “imagineering” as a toolkit for achieving this.

Today, Walt Disney Imagineering is the creative engine that designs and builds all Disney theme parks, resorts, attractions, and cruise ships worldwide, and oversees the creative aspects of Disney games, merchandise product development, and publishing businesses.

At the heart of this process is the “Imagineering Pyramid”.

Even if you’re not building a theme park, the Imagineering Pyramid can help you plan and achieve any creative goal. The pyramid is formed from from the essential building blocks of Disney Imagineering, and teaches you how to apply the pyramid to your next project, how to execute each step efficiently and creatively, and most important, how to succeed.

The principles in the Imagineering Pyramid each fall into one of five categories or groupings, each of which forms a tier within the pyramid.

The tools for imagineering are then an arrangement of fifteen important Imagineering principles, techniques, and practices used by the company in the design and construction of Disney theme parks and attractions.

Tier 1: Foundations of Imagineering

The bottom tier of the pyramid includes the foundations, or “cornerstones”, of Imagineering. These principles serve as the base upon which all other techniques and practices are built. There are five Imagineering foundations:

- It All Begins with a Story – Using your subject matter to inform decisions about your project

- Creative Intent – Staying focused on your objective

- Attention to Detail – Paying attention to every detail

- Theming – Using appropriate details to strengthen your story and support your creative intent

- Long, Medium, and Close Shots – Organizing your message to lead your audience from the general to the specific

Tier 2: Wayfinding

The second tier is focused on navigation and guiding and leading the audience, including how to grab their attention, how to lead them from one area to another, and how to lead them into and out of an attraction. The four Wayfinding principles include:

- Wienies – Attracting your audience’s attention and capturing their interest

- Transitions – Making changes as smooth and seamless as possible

- Storyboards – Focusing on the big picture

- Pre-Shows and Post-Shows – Introducing and reinforcing your story to help your audience get and stay engaged

Tier 3: Visual Communication

The third tier includes techniques of visual communication that are used throughout the parks in different ways. You’ll find examples of these in nearly every land and attraction. These principles include:

- Forced Perspective – Using the illusion of size to help communicate your message

- “Read”-ability – Simplifying complex subjects

- Kinetics – Keeping the experience dynamic and active

Tier 4: Making It Memorable

The fourth tier includes practices focused on reinforcing ideas and engaging the audience. It is the use of these techniques which helps make visits to Disney parks memorable. These include:

- The “it’s a small world” Effect – Using repetition and reinforcement to make your audience’s experience and your message memorable

- Hidden Mickey’s – Involving and engaging your audience

Tier 5: Walt’s Cardinal Rule

The top tier contains a single fundamental practice employed in all the other principles. I call it “Walt Disney’s Cardinal Rule”:

- Plussing – Consistently asking, “How do I make this better?”

The Disney+ documentary series, The Imagineering Story, has also been published as a new book that greatly expands on Leslie Iwerks’ movie of the fascinating history of Walt Disney Imagineering.

The legacy of Walt Disney Imagineering is covered from day one through future projects with never-before-seen access and insights from people both on the inside and on the outside. So many stories and details were left on the cutting room floor, the book allows an expanded exploration of the magic of Imagineering, including:

Sculptor Blaine Gibson’s wife used to kick him under the table at restaurants for staring at interesting-looking people seated nearby, and he’d even find himself studying faces during Sunday morning worship. “You mean some of these characters might have features that are based on people you went to church with?” Marty Sklar once asked Gibson of the Imagineer’s sculpts for Pirates of the Caribbean. “He finally admitted to me that that was true.”

In the early days, Walt Disney Imagineering “was in one little building and everybody parked in the back and you came in through the model shop, and you could see everything that was going on,” recalled Marty Sklar. “When we started on the World’s Fair in 1960 and 1961, we had 100 people here. And so everybody knew everything about what was happening and the status of [each] project, so you really felt like you were part of the whole team whether you were working on that project or not. And, you know, there was so much talent here.”

Here’s a one page summary of imagineering by the illustrator Jeremy Waite:

The great Tom Peters said of the book “I can’t exaggerate the importance and the originality of this book. And that is NOT hyperbole. Both/And provides us with a novel and unspeakably powerful and instantly usable way to reframe almost any problem. The argument is flawless. The case studies are engaging and powerful. And every significant point is backed up by unassailable research.”

“The Four Workarounds”

How the World’s Scrappiest Organizations Tackle Complex Problems

Real-world problems need real solutions. Often “perfect” just isn’t an option, and we need something easy, smart, and quick: we need a “workaround”, a deviation from the norm.

Paulo Savaget has produced a richly illustrated guide to how to work around rules and norms to solve complex problems, with examples from areas as diverse as cryptocurrencies and medicine distribution. Savaget outlines the managerial and domestic benefits to make a wider point about the advantages of adopting a “workaround mindset”.

From remote Zambia to the waves of the North Sea, Brazilian mines to American biohackers, The Four Workarounds shows how seemingly intractable problems have been solved using unconventional tactics. Through these cases – from public urination to the challenges of delivering life-saving medicine to remote communities – we see how some of the world’s most admired companies are already using Savaget’s research to transform the ways they do business.

Savaget draws examples from organizations dedicated to social action that have made an art form out of subverting the status quo, proving themselves adept at achieving massive wins with minimal resources.

They do this by employing four particular workarounds: the piggyback, the loophole, the roundabout, and the next best.

The “piggyback” solution is when you look for something that’s already working and then pair it with your current goal. Your workplace might have a robust mentorship program, but little formal support for new hires — and coupling those resources could help new hires see the same benefits.

The “loophole” solution is where you look for ambiguity in existing rules. It’s similar to where laws might differ by country, and therefore travelling to another place to avoid falling foul legally, Savaget suggests.

“Real-Time Leadership”

Find Your Winning Moves When the Stakes Are High

The best leaders, in the biggest moments, know how to read the situation, respond in the most effective way possible, and move forward. You can, too, according to David Noble and Carol Kauffman.

The hardest part of leadership is mastering the inevitable high-risk, high-stakes challenges you will face. Whether you’re making a split-second decision when your business is knocked sideways or you’re finding the best strategy to navigate business-critical long-term circumstances, how can you be in peak form in those most crucial moments?

We all have default reactions to things, and under pressure we become an exaggerated version of ourselves. We are then vulnerable to slide into our automatic ways of reacting. Often these do not serve us, or those we lead and care about. It’s important to learn to make inner space, so as to defy your default mode of acting, allowing you to make the most of every moment.

Finding your winning moves when the stakes are high means being able to have choices at your fingertips when you need them. Victor Frankl wrote that there’s a space between stimulus and response, and in that space is our freedom. But, what can you do with that freedom? What should you focus on, what lifelines do you need to hold onto? Can you slow time down, look around, and gain sense of what you need to focus on? Can you identify what really needs to get done, what inner resources you can access? Are you able to see others clearly, connect with them, and send the right signals? If you could, what would that be like? How much would that serve you?

Here are three examples of stimuli: You are in a major interview and you’re tanking. Will you go into default mode, or can you make a space? You are with a coworker or an extended family member and suddenly they start spouting opinions that are toxic to you. Will you go into default mode, or can you make a space? You want to buy a house or acquire a company and your finances are strained. Will you go into default mode, or can you make a space?

We have a number of ways to help make space, defy your default mode, and find freedom to make the choices you want. We summarize everything we know and clumped it into an acronym so you could remember it in real-time: M.O.V.E.

Gymshark, the activewear brand created by Ben Francis has grown rapidly over recent years, largely serving a young audience, selling online direct, powered by social influence.

It started out by drop shipping bodybuilding supplements online, before branching out into designing and producing its own line of activewear on a made-to-sell basis. By 2016, Gymshark was labelled the fastest growing company in the UK – and, in 2020 was named the UK’s fastest-growing fashion brand globally, boasting an average increase in international sales of 115.7% over the previous two years.

Today, Gymshark sells its fitness apparel direct-to-customer in almost 200 countries, and has translated its website into 13 languages to support its international growth. Though its initial birth and growth has been completed online, Gymshark opened its first ever physical store in October 2022 – almost a decade after the company was first founded. To highlight the success of the company, its flagship store is located on London’s prime shopping street – Regent Street.

This innovative flagship store is where Gymshark effortlessly incorporates its trusty digital technologies into a physical, in-person experience – its aim is to not only sell its clothing, but also allow the community to experience the essence of Gymshark. In addition to traditional clothing rails, the store boasts a fitness studio, or ‘The Sweat Room’, the fitness answer to Apple’s ‘Genius Bar’ called ‘The Pro Bench’, a Joe & The Juice concession, and a multipurpose area known as ‘The Hub’.

For some people, their Gymshark experience starts digitally – the latest video or recommendation on Instagram or TikTok, browsing the online store or app – for others it will start by walking into the store, exploring the Gymshark brand, and its related services. But these are not either/or, nor a linear flow. Brands like Gymshark have become immersive environments, fusing physical and digital as one, where the customer experience becomes a circular journey, where data enables great personalisation, where brands are no longer names of producers or products, but all about the customer and their community.

“Liquid CX” is all about thinking like a customer, enhancing their experience either through efficiency or added value, giving them more choice, serving them more personally, engaging them more deeply, in ways that drive relevant loyalty, and also finding new revenue streams.

Liquid CX is built on a board portfolios of physical and digital assets that can fuse together in a seamless and personal way for each customer. It goes more options for how people can interact with your brand and buy, how they want their products delivered, and what services they want to take advantage of in-store. This choice is what keeps customers loyal and allows them to choose the right journey that suits their needs in that moment.

For instance, with integrated stock management data, retailers can offer flexible fulfilment, giving customers the opportunity to click and collect, buy online pick-up in store, or buy in store deliver home – whichever methods work best for the products on sale and customer needs. This stock data also allows retailers to use stores as local hyper-fast delivery hubs and offer ‘endless aisle’ functionality, giving customers the opportunity to obtain any product they want, regardless of it being in stock in store.

In-person experiences can be elevated for customers with personalised discounts based on past or predicted purchases, and location-based push notifications. Cashier free shopping or mobile POS allow for frictionless checkout, whilst augmented reality (AR) overlays can help customers to source product information autonomously. With the right tools and data at their fingertips, store associates can deliver unforgettable in-store clienteling, giving customers instant information on products and availability without running to the stockroom, and offering advice on items that may be of interest, based on customers’ past purchases.

Liquid CX is most commonly found in fashion retail, but increasingly in food stores, music concerts, art galleries and sporting arenas too.

According to a recent McKinsey study, customers will expect hyper-personalised “liquid” experiences by 2025. Of course, with the help of data analysis and AI tools, retailers today can offer incredibly personalised experiences to their customers, both online and in-store. And the more digitalised the experiences, the more opportunities to capture and use customer data in useful ways

Some great personalisation activities are:

- Showing relevant product recommendations

- Tailored messages and targeted promotions

- Triggers based on customer behaviour

- Communicating timely at key touchpoints

- Curate content based on the customer’s specific interest

According to a 2022 IBM consumer study, 27% of all consumers say that “liquid” shopping is their primary buying method. In the case of Gen-Z, this number goes up to 36%. Knowing that Gen-Z consumers are born from 1997 onward, they hold plenty of purchasing power and will continue to do so even more.

Retail stores have yet to understand and experience all the benefits of “liquid” shopping. There are so many benefits and reasons for physical-centred stores to have an online presence (and equally digital-centred stores to be more physical):

- A more personalised shopping experience

- Better customer satisfaction and loyalty

- Greater customer reach through multiple online and offline channels

- Increased engagement and multiple touchpoints for customers to interact with your brand

- Increased foot traffic thanks to in-store pickup or returns for online purchases

- A competitive advantage among other retailers

- Better operational efficiency, reduced waste, and reduced costs

And, of course, perhaps the biggest benefit of providing “liquid” experiences as a retailer is the possibility to analyze consumer behaviour with unique sales data. Leveraging these insights you canand optimize every aspect of your store, especially things like inventory management, marketing, or customer service.

Perhaps the best example of a successful personalizsd shopping experience is the retail giant Sephora.

In March 2020 when the pandemic hit, Sephora closed its physical stores. But, instead of seeing it as a setback, they embraced the situation and pivoted to appointment-based personal shopping and VR demos and tutorials.

As they saw their efforts paid off, they introduced their AR fitting room and Color IQ technology that scans a customer’s skin to recommend matching foundations.

As the cherry on top, they provided free shipping, same-day delivery, and flexible in-store or curbside pickup options.

Sephora’s successful implementation of these personalized shopping experiences led to increased market share even after the pandemic’s impact diminished.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RgNuwb9lpeg

This week I met Quantic Brains, a Spanish AI-based start-up which is reinventing the way content is created for books, videos and games.

I sat down with founders Manuel Lucania and Julio Covacho, chose a title for my next book, and within 10 minutes it was done. A structured narrative, extensively researched, with commentary and insight, which I could then edit and enhance, all about my specific, chosen topic.

When I normally write books – I have written 10 of them, starting with Marketing Genius, through to the most recent, Business Recoded – it takes me about 18 months at least. After 6-12 months of sitting around struggling to focus on a compelling topic, with new angles and insights, it then takes me another 6-12 months of long hours researching, typing, retyping, my 80000 words.

I found the future in Madrid.

Quantic Brains are actually more focused on video and gaming content – how to use AI to instantly create characters, imagery, special effects, music, voiceovers and much more for the visual arts.

“Our vision is that in 5 years most of the films, series, and video games will be automatically generated with none or very little human intervention. Our goal is to democratize audiovisual content creation with AI powered tools for professionals and non professionals.”

“We develop AI brains that encapsulate different sets of skills to automatize character behaviours (talk, walk, swim, fight…). Once the character is on scene, it interacts with other characters and with exclusive smart objects that can only be used by our brains (sword, piano, phone, ball).”

Maybe my next book will be available very soon …

Peter Drucker, the Austrian-born consultant turned academic, is often regarded as the father of modern management thinking. He also played a crucial role in the development of consulting firms McKinsey and Bain.

Although he authored 39 best-selling management books, Drucker was more motivated by working directly with business leaders, coaching and challenging them to think different, bigger and better.

Here are 15 of his wisdoms

- Whenever anything is being accomplished, it is being done by a monomaniac on a mission.

- The purpose of a business is to create a customer.

- The best way to predict the future is to create it.

- If you want something new, you have to stop doing something old.

- Knowledge is the source of wealth. Applied to tasks we already know, it becomes productivity. Applied to new jobs, it becomes innovation…

- People who don’t take risks generally make about two big mistakes a year. People who do take risks generally make about two big mistakes a year.

- Innovation opportunities do not come with the tempest but with the rustling of the breeze.

- Innovation is the specific instrument of entrepreneurship that endows resources with the capacity to create wealth.

- Since we live in an age of innovation, a practical education must prepare a man for work that still needs to be created and can be clearly defined.

- Marketing and innovation make money, produce results and create wealth. Everything else is cost.

- Innovation requires us to identify changes that have already occurred systematically — and then to look at them as opportunities. It also requires that we abandon rather than defend yesterday.

- We need an entrepreneurial society where innovation and entrepreneurship are regular, steady, and continuous.

- The enterprise that does not innovate ages and declines. And in a period of rapid change such as the present, the decline will be fast.

- No other area offers more stimulation for an innovator than unexpected success.

- Effective innovations start small. They are not grandiose. They try to do one specific thing.

Drucker, born in Vienna, Austria, in 1909, passed away at 95 on November 11, 2005. He worked as a management consultant before becoming a writer and academic, focusing on the operation and leadership of modern business corporations. Drucker was interested in understanding how people interacted in ways that led to success or failure and sought to systematize his thinking to make it accessible to others. Despite being highly contrarian at the time, he gained prominence during the Japanese economic miracle, as his work led to a renewed respect for Japanese practices after WWII.

Drucker is known for coining the term “knowledge worker” and believing this type of employee was crucial for improving business results. He was influenced by economist Joseph Schumpeter, who used the phrase “creative destruction” and focused on people’s behavior rather than commodity fluctuations to understand markets and productivity. He worked as a professor, consultant, and industrial psychologist. His work on management philosophy in European companies paved the way for a more democratic approach to decision-making in American companies.

Drucker believed management was more than just a profit-chasing activity and defined it as one of the “liberal arts.” He drew lessons from history and religion in his work. He argued that businesses needed to have a greater purpose than just profit-making, with a solid dedication to society, to last through the many challenges that occur in the life cycle of a business. He presciently predicted in his book “Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices” that managers of significant institutions, especially in industry, must take responsibility for the common good in modern society, or else no one else will.

Drucker was a palm reader as much as a philosopher and was known for making predictions that often came true and was criticized for occasional misjudgments. Despite this, he remained a prominent figure in management theory and philosophy. He believed the nation’s financial center would eventually shift from New York to Washington. While he was criticized for this prediction, it is now seen as accurate with the introduction of Sarbanes Oxley and Dodd-Frank regulations.

Joe Tsai was one of 17 friends who were invited to Jack Ma’s Hangzhou apartment in February 1999, an evening where they developed a plan to create a new digital platform to “revolutionise the Internet industry”.

They called it Alibaba.

Tsai gave up a Hong Kong-based private equity investment job at Investor AB, which is the main investment vehicle of Sweden’s Wallenberg family, to join Alibaba in 1999 for a monthly salary of $50.

Today, the billionaire co-founder of Alibaba, and also owner of the Brooklyn Nets, is taking over as chairman of the e-commerce giant.

His challenge is huge. Alibaba has grown over the last 20 years to become one of the world’s largest retailers. But in recent times, since Jack Ma famously fell out with the Chinese government, the business has struggled. Amid rising competition, and the Covid pandemic, Alibaba’s market value has fallen by around 70%.

As part of a radical management shake-up, the 59-year-old Tsai is replacing Daniel Zhang as chairman. Eddie Wu, another cofounder, will be taking over as CEO from Zhang when he steps down in September 2023.

Zhang will focus on leading Alibaba’s cloud computing business as the unit prepares for an IPO that may happen as early as next year, according to recent Alibaba announcements.

Jack Ma, who is still China’s seventh-richest person with a net worth of $24 billion, stepped down from Alibaba’s helm in 2019, and has spent the recent years lying low and travelling abroad after his criticism of the country’s banking system in 2020, which led to his falling out with the Chinese government, and accelerated departure from Alibaba.

Tsai, who is a longtime confidante of Ma’s, will need to fight increasingly strong competition. Born in Taiwan, he also holds a Canadian passport, and prefers a relatively hands-off management approach.

The current $230 billion company, has lost more than 70% of its value since peaking in late 2020, as Beijing’s crackdown on the entire internet industry has caused investors to reassess Alibaba’s outlook. Meanwhile, competition has been tougher than ever – in particular, the fast-growing Pinduoduo, and short video platform Douyin.

Tsai becamee Alibaba’s chief financial officer, a position he held until 2013. He then moved to an executive vice chairman role, responsible in part for the e-commerce business’ financing activities and strategic investments.

Today, Tsai still derives part of his $7.7 billion net worth from a 1.3% stake in Alibaba.

He has also built a sports and entertainment empire. Tsai took full control of the Brooklyn Nets in a $2.35 billion deal in 2019 after first acquiring a 49% stake from Russian billionaire Mikhail Prokhorov two years earlier. And his other sports franchises include ownership of the New York Liberty from the Women’s National Basketball Association, and two lacrosse teams, the San Diego Seals and Las Vegas Desert Dogs.

He holds a bachelor’s degree in economics and East Asian Studies from Yale College and a juris doctor degree from Yale Law School. His early career experience includes an associate attorney job at New York-based law firm Sullivan & Cromwell LLP, and general counsel of New York-based buyout firm Rosecliff, Inc.

Now, a significant portion of his wealth is managed through his Hong Kong-based family office Blue Pool Capital, which holds stocks, venture capital investments and his sports assets.

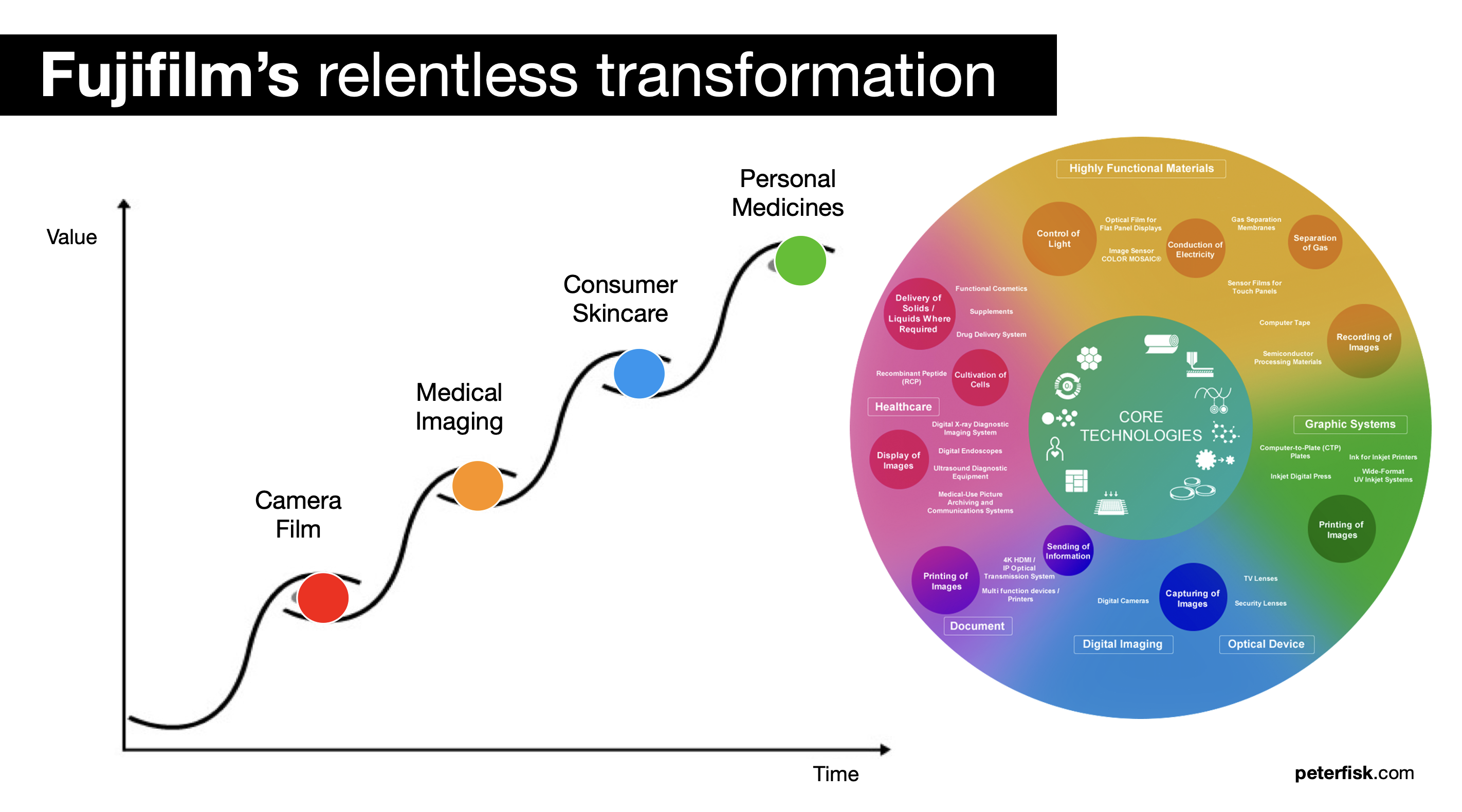

Shigetaka Komori, former CEO of Fujifilm, had a mantra, “never stop transforming.”

As a result, the Japanese business has created innovative solutions in a wide variety of fields, leveraged its imaging and information technology to become a global presence known for innovation in healthcare, graphic systems, optical devices, specialist materials and other high-tech areas.

In the 1960s, Fujifilm was a distant second place to Kodak in the photographic film market. But today, digitalisation has transformed how we take photos, Kodak is gone (bankrupt in 2012), and Fujifilm has shifted focus and resources into new areas.

In 2000 the film-related business accounted for 60% of Fujifilm’s sales and 70% of its operating profit but fell to less than 1% within a decade. The traditional photographic imaging business, the core of the business, was largely replaced by other types of imaging, such as for healthcare.

“Whilst Kodak tried to survive in a declining market, Fujifilm looked to new futures” says Komori, when contrasting how the two companies responded to market change.

Imaging rapidly evolved into digital information, and a vast range of new businesses emerged in areas from medical system to pharmaceuticals, regenerative medicine to cosmetics, flat panel displays to graphic systems.

As an example, Fujifilm’s cosmetics business started in 2006 with the launch of its Astalift skin-care products, which then extended into make-up, and from them into other types of medical and wellbeing solutions. Whilst camera film and cosmetics might seem unrelated, camera film happened to be the same thickness (around 0.2 mm) as human hair. Collagen was used in its film to retain the material qualities, such as moisture and elasticity, over time. This expertise in manufacturing collagen is also fundamental to making skincare products.

Fujifilm introduced medical diagnostic imaging systems using its digital camera technology, which then gave it a platform for doing fundamental research into new medicines. Drug development is increasingly built on informatics, such as genetic analysis, fields in which Fujifilm could combine its expertise, giving it an advantage over traditional pharma companies.

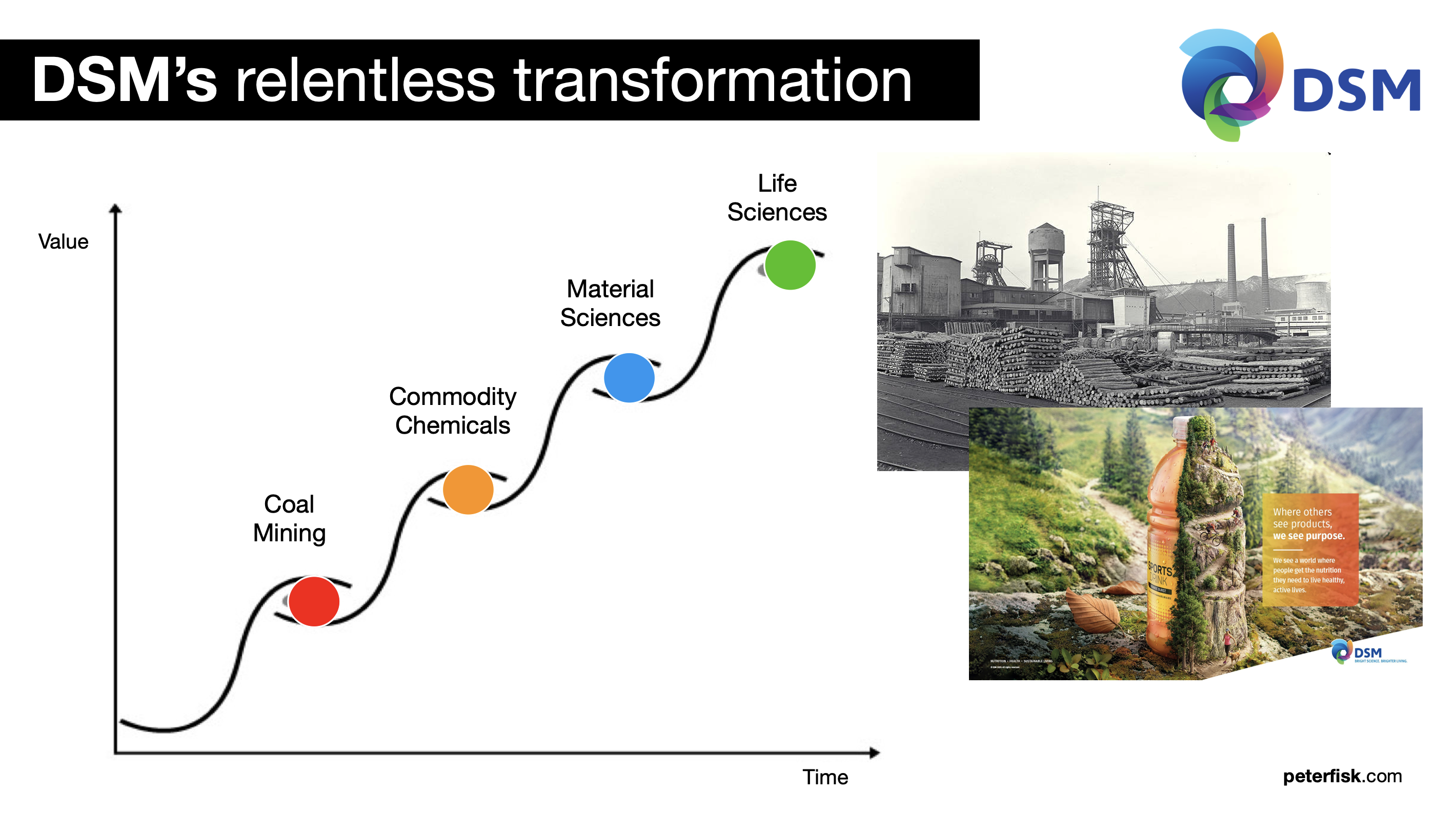

Look at many of the other long-surviving companies around the world, and they have evolved into something very different from how they started.

Amazon started with a vision to be the world’s largest online bookstore, and then evolved into an everything store, then into a diverse portfolio of businesses and services, including physical stores like Amazon Fresh and Amazon Style.

Even more remarkable are the companies that started out as state-owned utilities then evolved into commercial innovators. Nokia started at Finnish forestry. Orsted started as Danish power stations. DSM started as Dutch coalmines.

Infinite and invincible

In his book “The Infinite Game”, Simon Sinek explore how businesses can achieve long-lasting success, a relentless approach to transformation and growth, and sustained long-term value.

“In finite games, like football or chess, the players are known, the rules are fixed, and the endpoint is clear. The winners and losers are easily identified” he says. “In infinite games, like business or politics or life itself, the players come and go, the rules are changeable, and there is no defined endpoint. There are no winners or losers in an infinite game; there is only ahead and behind.”

Many businesses struggle because their business has a finite, or fixed, mindset. They set themselves an internal goal to be the best at something, or to launch a specific product, and they end up being a slave to it. Such narrowly-defined, sales-targeted, product-centric businesses find it difficult to break out of their current approach. They only know how to do more of the same with diminishing returns. Sales stagnate, momentum is lost, innovation slows, energy dips, and they lag behind.

Leaders with an infinite, or growth, mindset – not just in terms of experimenting to find new ways forwards, but in terms of their whole approach to strategy and innovation – do much better. They are purpose-driven, growth targeted, customer-centric. This builds direction and alignment, momentum and energy. These factors drive them naturally to keep evolving, to adapt and innovate, to move with a changing world. They even create a rhythm of change ahead of the market, and so can shape the world to their advantage.

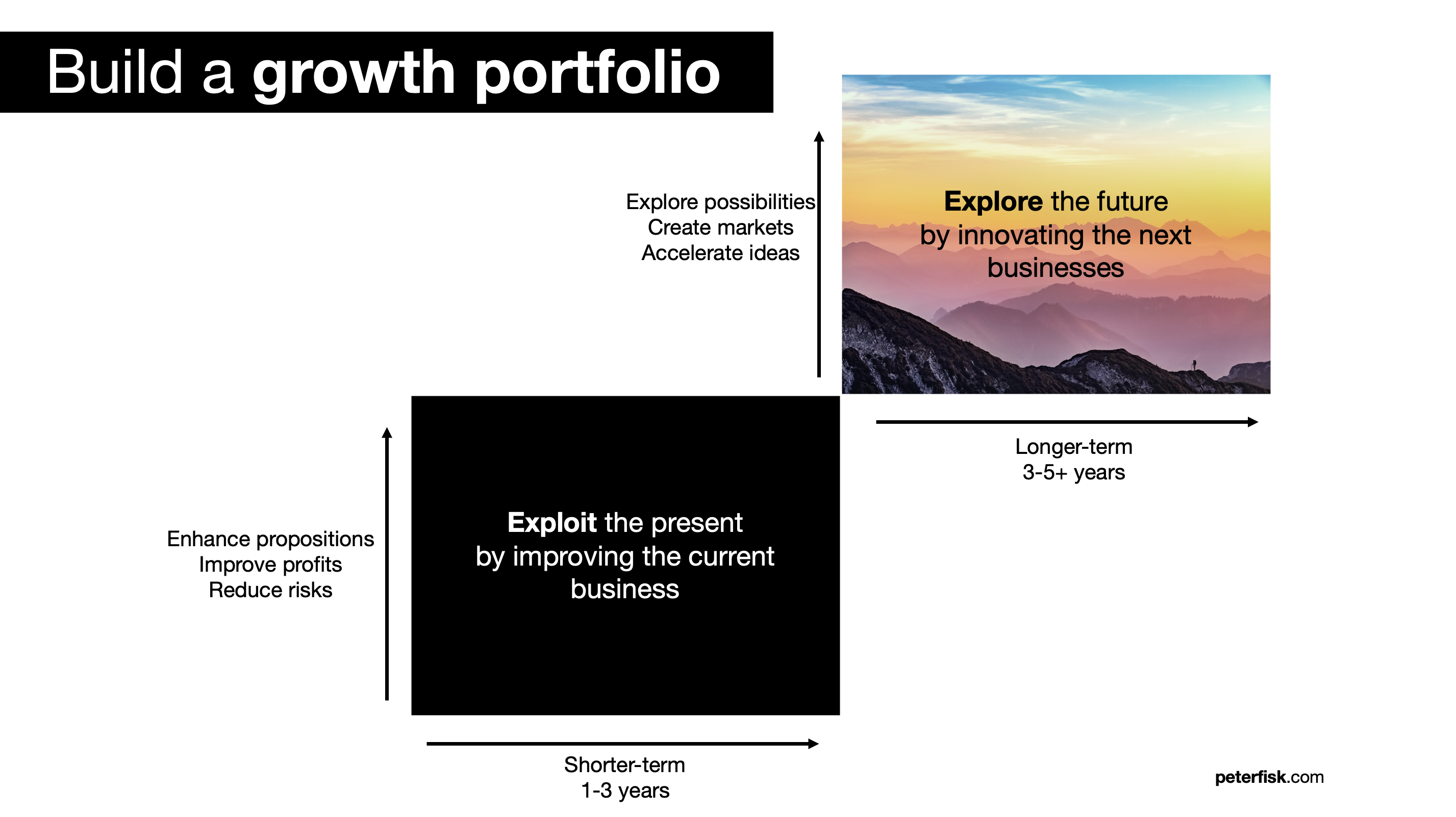

Building a growth portfolio

Alex Osterwalder and Yves Pigneur famously created the business model canvas, a one-page diagram in which to capture the essential components of any business model, and crucially to explore the connections and trade-offs which exist between different choices. However, they increasingly found that the best companies develop a series, or portfolio of business models, which can serve them over time.

Their more recent book is “The Invincible Company” because companies who build a growth portfolio are sustained over time, not just in mindset, but also by a whole series of great ideas, innovations and business models that ensure its success today, and into the future.

Invincible companies manage a dynamic portfolio of established and emerging businesses – to protect established business models from disruption as long as possible, while simultaneously cultivating the business models of tomorrow. They need to “exploit” the present, and “explore” the future

- Exploit the present requires leaders to manage and improve the existing businesses, focusing on their profitability, and their risk of disruption by new competitors, new technology, new markets, or regulatory changes.

- Explore the future requires leaders to also search for new areas of growth, evaluating the potential profitability of new ideas which is drive by size and scalability, and also the risk associated with innovation, and how to make new ideas more certain.

To remain relevant and prosperous companies need to develop truly “ambidextrous” organisational structures which can create the future, whilst also delivering today. Innovation becomes just as important as delivery, but requires a distinctive culture, distinctive skills and metrics in order to be explorers of the future.

Leading for relentless growth

Leaders, themselves, need to be ambidextrous – to be the delivers of today, and also the creators of tomorrow.

Komori’s success has not come through creating one business, but a sequence of business concepts which keep building off each other. This sequence might take the form of leveraging distinctive capabilities with various applications into different sectors like Alphabet has done, or it might be about taking more businesses to the same audience as Apple, or it might be a series of ways of working within the same sector as Microsoft.

Amazon is a good example of a company that intentionally manages a diverse portfolio of existing and promising new business models. The company continues to produce growth with its existing businesses (online retail, AWS, logistics), whilst also developing a portfolio of potential future growth engines that may become big profit generators one day (Alexa, Echo, Dash Button, Prime Air, Amazon Fresh, etc).

Long-term sustained growth is built on a portfolio of short and long-term innovative business models. Such “invincible” companies can better allocate capital and resources at each stage of development. A culture and process that drives a continuous flow of new ideas and innovation is much more likely to sustain your business in turbulent times and uncertain futures.

© Peter Fisk 2023. Excerpt from his book Business Recoded.

Every market is uncertain. Every business leader needs to lead in a blur of change.

Volatile, dynamic environments bring new challenges to decision-making. Executives still yearn after stable environments, where the future is predictable, and data about past years can be used to evaluate future choices. No longer.

At the same time we have more data than ever before – customer insight, financial analysis, operational performance – but its largely all backwards looking. Yes, we can look for patterns and build projections, but they are based on future assumptions. Not easy. And trying to get even more specific, to build a business case, for example a discounted cashflow analysis, to demonstrate profits over future years is even harder.

In a data intensive world, executives don’t like to be intuitive. They feel naked.

While huge amounts of data, particularly driven by the realtime tracking of digital platforms and devices, allow us to be much more granular in our short-term behaviours, to optimise the present, to personalise to customers, it actually hinders our confidence, to look forwards, to imagine, to be strategic.

The Information-Action Paradox

Innosight, the consulting firm led by Scott Antony, describe this paradox particularly as leaders face the need to change. They see digitalisation, disruption and discontinuities ahead, but they feel incapable of action.

On one hand, they need convincing data to make the case that transformation is necessary and to show that their companies are about to find themselves on “burning platforms” –when there are limited options to change. But by the time public data about trends and market shifts is convincing, the window of opportunity has shrunk, if not disappeared.

So how can leaders avoid ending up on a burning platform then? The key is to act before compelling data is widely available, a challenge that is complicated by the lack of information in periods of uncertainty.

In a new article “Persuade your company to change before it’s too late“, Scott introduces a simple conceptual model to help companies map out where they stand when it comes to their knowledge and their ability to act. They call it the “information-action paradox.”

Of course there is a powerful role for data in business. First because today’s markets and activities are fast and fragmented, with data enabling focus and optimisation. And the increasingly powerful AI platforms enable futures to be anticipated, although only based on what they know so far.

We still need human beings to lead, with vision and imagination.

Tools to Lead in an Uncertain World

Scenario planning is complex and easy. Infinite possibilities can create a rich diversity of possibilities and options, but also confusion and chaos. The challenge is not to predict the future, but to be prepared for it.

It’s a great approach to use with boards and executive teams to build a rich conversation around future possibilities, future alternatives, future choices.

My first experience of scenario development was with Royal Dutch Shell, the oil business, which started using the technique in 1971, to understand the implications of oil shocks, and as we reach peak oil, the ways in which the world can shift to renewable energy. Shell’s process is complex, although produces fascinating stories of possible futures.

A simpler approach, to stretch thinking and debate possibilities, can be achieved as a team within a few hours, largely using the insights and ideas in participants heads, rather than requiring huge amount of prepared data. The collaborative process, the rich discussion, the strategic stretch, is what matters. I use these steps

- Future drivers: Consider the potential drivers of change that will shape the future of your broader industry, and the world of your customers. You could use megatrends as a stimulus, or develop your own drivers based around possible social, technological, economic, environmental and political (STEEP) changes.

- Critical uncertainties: Select a number of particularly interesting drivers and describe extreme opposite ways in which they might play out (polarities). For example, will retail shift primarily online with home deliveries, or into a rich social experiences on the high street? Consider the extremes, even if a balance seems likely.

- Plausible scenarios: Bring together some of the most interesting polarities. Most simply do this be creating 2×2 boxes built on any two polarities. For example, the retail shift, alongside economic boom or recession, or strong or weak sustainability focus. Each quadrant of each 2×2 is a mini scenario. Repeat, and discuss.

- Strategic implications: With a large number of mini scenarios from the group, bring them together in a rich picture of possible futures, sharing and discussing as you progress. Evaluate as a team the potential timeframes and certainties. How do they cluster? Which are most risky, and most rewarding? Which do we like most?

With a better understanding of possible futures, you can start to future-proof your business against the worst scenarios, but also choose the futures which you would like to create.

A brand strategy should should be a clear reflection of the ideologies and beliefs that the company, or product or person, wants to signify. And once we know who we are, we can then target people who see the world the way we do.

“Culture moves forward on the basis of a simple question: do people like me do something like this? If the answer is yes, we do it. If not, we don’t,” says Marcus Collins. “This sway is super powerful, which makes culture arguably the biggest cheat code in the business.”

In order to engage with its community, a company must understand who they are. “The company has to know what it believes, how it sees the world and how they show up in the world relative to these ideologies. Once we know who we are, we can then target people who see the world the way we do,” he says. “These people are your ‘collective of the willing’.”

“What does it mean to engage? If you want people to visit your website and watch a video, be more concrete with your language and put it that way,” Collins says. “That specificity will help teams focus their efforts on creating solutions that deliver against that ambition as opposed to the fuzzy language of getting people to engage.”

With 30 years experience in the marketing world, I’ve got to know some of the best marketers, brands and agencies. Wieden+Kennedy, the agency that grew on the coat tails of Nike, is one of the most creative.

Marcus Collins is their head of strategy, while also moonlighting as clinical assistant professor of marketing at the Ross School of Business, University of Michigan. His deep understanding of brand strategy and consumer behavior has helped him bridge the academic-practitioner gap for blue-chip brands and startups alike.

We all try to influence others in our daily lives. Whether you are a manager motivating your team, an employee making a big presentation, an activist staging a protest, or an artist promoting your music, you are in the business of getting people to take action. In his first book For the Culture, he argues true cultural engagement is the most powerful vehicle for influencing behavior. If you want to get people to move, you must first understand the underlying cultural forces that make them tick.

Collins uses stories from his own work as an award-winning marketer, from spearheading digital strategy for Beyoncé, to working on Apple and Nike collaborations, to the successful launch of the Brooklyn Nets NBA team, to break down the ways in which culture influences behaviour and how readers can do the same. With a deep perspective, and built on a century’s worth of data, For the Culture gives readers the tools they need to inspire collective change by leveraging the “cheat codes” used by some of the biggest brands in the world.

Jay Norman, Spotify’s Global Head of Music Marketing says of the book “Diving deeply into what moves real people, not personas and archetypes, Collins gives us a look into cultural nuances we can use to make meaningful connections and drive action. This book is insightful, enlightening, and sure to challenge any preconceived notions about communicating with the world. Talk the talk, walk the walk, and always do it for the culture.”

How did Collins end up as Chief Strategy Officer of Wieden+Kennedy?

“I started off as an engineer, surprisingly, because I thought material science and polymers were interesting. I realized, probably, it’s the best way to describe material science and engineering. Interesting, yes, but definitely not cool. When I graduated from undergrad, I went into the music business, did a startup. I was writing and recording music for a living, and realized the music industry sucks. After a little bit of success, then went to get my MBA, then went into marketing.

I found myself doing partner marketing at iTunes, and ended up meeting Matthew Knowles, who’s Beyonce’s father. He says, “Let me get this straight. You’re an engineer, you started a music company, you have an MBA, you worked at iTunes, and you’re Black. Dude, you don’t exist. You’re not real. You’re a unicorn.” I said, “No, I’m real.” Totally, he’s said, “Well, you should come run digital strategy for Beyonce.” I was like, “Yes, I should totally do that.”

I moved to New York, ran digital strategy for Beyonce before moving into the world of advertising, actually, with our mutual friend, Avi Savar of Big Fuel, really learned the ins and outs of social media. What does it mean to be a social marketer? It was like bootcamp for society in a lot of ways. While I was there, I ended up meeting Steve Stoute. Stoute is a once music guy turned agency guy, kind of a hybrid of the two. It felt like it was the perfect intersection of the things that I had always been excited about.

He offered the opportunity to build a social practice of translation. I went and did that, and during that time, launched the Made in America Music Festival for Budweiser, launched Chris Paul’s campaign for State Farm, moved the New Jersey Nets from New Jersey to Brooklyn, and became the Brooklyn Nets, just like some really cultural work. I started to really understand what it meant to impact culture.

From there, I moved over to Doner and started working in the world of academia, while also working at Doner in Detroit, my hometown, ended up getting a PhD, really marrying academia and practice. This academic gap is trying to bridge, and now find myself here at Wieden, running strategy here in the New York office, and it’s been a blast.”

Some of the provocative ideas emerging from the book include

- Identity is more important than value propositions. Launching the campaign that moved the Brooklyn Nets from New Jersey to Brooklyn suggested that identity is more important than value propositions.

- You don’t “build” community, you “facilitate” community. Working with Beyoncé taught him that you don’t “build” community, you “facilitate” community.

- When people feel seen, they also feel heard. Launching the Real Tone technology for Google’s Pixel 6 taught him that when people feel seen, they also feel heard.

- If you have an idea and it’s logical but people don’t get it, then you’re probably on to something even if people make you feel like you’re wrong. He talked about his own past as a songwriter, growing up listening to hip hop, and how that has inspired the phraseology he has used in marketing. In fact, “that’s a bar” is how he refers to a clear, evocative phrase that people can register quickly, like the “1,000 songs in your pocket” description of the iPod that Apple used during its launch.

- The most powerful skill you can have is the ability to communicate—clearly and evocatively. He learned that the most powerful skill you can have is the ability to communicate – clearly and evocatively – during his time at Apple where Suwanjindar would question even his most basic statements to see if he could make them clearer.

“Culture is a meaning-making system. Culture is the way by which we make meaning. While the brand may intend to mean one thing, it doesn’t necessarily align to what it means in the minds of people. The brand may say, “We think we’re cool. We’re hip. We see the world this way.” People go, “No, we don’t see you that way,” and therefore, is a great incongruence. It’s not enough for us to have a desired meaning. We have to understand what we mean in the eyes of people, and then use our marketing communication to close the gap.”