Cement production is responsible for about 8% of global carbon dioxide emissions and 5.5% of total global greenhouse gas emissions.

Although several companies are exploring solutions, many only partially reduce emissions or end up with a product that can’t be used as a one-to-one replacement in existing processes. Brimstone, a startup that raised a $55 million funding in 2022, makes Portland cement, the most common type, and cuts emissions by replacing one ingredient—limestone—with silicate rock, which, unlike limestone, doesn’t produce CO2 when it’s heated as part of the cement-making process. The process also creates silica, a by-product that can be used to replace another ingredient in typical cement, called fly ash, which usually is sourced from coal-fired power plants.

In addition, the silicate processing also creates magnesium rock, which naturally absorbs CO2 from the air. This means that if Brimstone’s cement is made with renewable energy, the process is actually carbon negative, meaning it stores more carbon than it emits. It’s also lower cost than conventional cement. Brimstone has proven that its technique works and is using its recent funding to erect its first plant, which will be operational in 2024.

A new process to make ordinary cement

Brimstone was founded by two scientists who grew up halfway around the world from each other, bonded in Beijing where they traveled to talk toilets and are now aiming to solve that massive cement problem.

Co-founders Cody Finke and Hugo Leandri overlapped while doing graduate work at the California Institute of Technology in 2017, where they were both working on wastewater treatment. But the pair really bonded when they both attended the Reinvented Toilet Expo in Beijing in 2018.

In 2022 Bill Gates’ climate finance firm, Breakthrough Energy Ventures, and DCVC, a Silicon Valley venture capital firm, announced a $55 million funding round in Brimstone, saying “We need to recognise that cement is a massive problem for climate and that nobody has figured out how to address it at scale without dramatically increasing costs or moving away from the regulated materials that the construction industry knows and loves.”

A new process to make ordinary cement

Normally, creating cement involves heating up limestone, which releases carbon dioxide. Even if the energy used to heat up the limestone is 100% clean, 60% of the carbon emissions would remain because of what is inherently in the limestone rock, Finke said.

Some companies are working to make climate-friendly cement by capturing the carbon dioxide and storing it underground or using it. Other companies innovating in the space make an alternate product that serves the same functions as cement but is not cement.

Brimstone’s process creates what’s known as ordinary Portland cement (OPC), but instead of using limestone, it involves grinding up calcium silicate rock and using a leaching agent to pull out the calcium. Calcium silicate makes up about 50% of the Earth’s crust, according to Finke, and is so common that it’s often crushed up and used to make gravel. The process is subject to four patents.

Incidentally, the company’s name comes from an archaic term for sulfur, which was used in a previous version of its process. “We no longer use sulfur, but we still use stones, and we have a fiery passion for decarbonization,” says Finke.

Investors like the company’s focus on creating industry-standard cement at a similar or cheaper price point, instead of an alternative that might be more expensive and have to clear new regulatory hurdles.

“Brimstone is the first company we’ve seen that can make the same exact material that we use today to build our buildings and bridges — ordinary Portland cement – but without carbon emissions and with the potential to cost the same as, or less than, traditional cement,” says Roberts.

In 578 BCE, Japan’s Prince Shotoku invited three immigrant Korean carpenters to build his country’s first Buddhist temple, Shitenno-Ji.

Buddhism was growing rapidly in Japan at the time, however the Japanese had no experience of building Buddhist temples, so they looked overseas for help. Shigemitsu Kongō was a renowned temple builder, and the royal family commissioned him to build the temple, which still stands today in Osaka.

Kongo saw an incredible opportunity. Buddhism was catching on fast, and he knew he could be kept busy for decades building temples. It turned out to be centuries. Over 14 centuries, in fact.

His construction company Kongō Gumi was founded in 578 AD, the oldest surviving company in the world.

In fact Kongō Gumi, still based in Osaka, traded as an independent firm until 2006 with the motto “Inheritance of techniques from 1,400 years ago to the future”.

It still exists today, building and maintaining Buddhist temples by hand with the Kongō family’s involvement, now as a subsidiary of construction giant Takamatsu.

In over 1400 years, that’s 40 generations of family leaders, the company was never left behind, never encountered a competitor it couldn’t match, and never made a single fatal mistake. The average modern company lasts for only 21 years. By contrast, Kongō Gumi outlasted Genghis Khan, the bubonic plague, the rise and fall of the shogunate, the industrial revolution, two world wars and Japan’s aggressive modernisation, to reach the dawn of the digital era.

It would be wrong to assume that the family firm, steeped in ancient Buddhist carpentry practices, somehow stayed still for all this time. Agility is nothing new – the ability to rapidly and effectively respond to opportunities and threats without losing the company’s coherent sense of long-term direction.

An example of this agility came during the Meiji restoration of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when the pro-Shinto authorities cracked down heavily on Buddhist practices, threatening the company’s traditional core business. Kongō Gumi responded by diversifying into commercial and residential construction, a smart move in a country that was modernising so quickly.

When the firm’s 37th leader Huruichi Kongō committed suicide in the interwar Shōwa depression, his widow Yoshie took the helm, breaking 1,300 years of uninterrupted male leadership. Faced with extreme financial pressure, she instituted key western-influenced reforms like separating managerial from practitioner roles.

Yoshie also found an ironically lifesaving new revenue stream during the Second World War, building wooden coffins. Even in the late 20th century, the business continued to adapt when circumstances required, becoming the first to use computer-aided design and concrete in traditional wooden temple construction. It was only when the Japanese property crash of the late 1980s saddled Kongō Gumi with unsustainable debt – at a time when donations to temples were also drying up rapidly – that the company finally faced a situation it was unable to survive.

What these episodes had in common was that Kongō Gumi’s leaders recognised major threats and opportunities, understood how important they were and what changes they required, and acted swiftly and decisively in response.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BO1dYcfin0c

Kongō Gumi stayed committed to traditional construction of extraordinary quality, maintaining trusted and reciprocal relationships with customers over many years, and the good name of the family – not just building temples.

For Kongō, the Meiji Restoration wasn’t a headwind, it was an existential threat. Critical thinking also allows agile firms to figure out an effective response by clarifying ideas, testing assumptions and probing weaknesses.

How much should we diversify? Should we focus our efforts here or there? What needs to be true for this plan to work, and how will we find out whether that’s the case? What happens if it doesn’t work as expected?

While it’s easy to associate the visionary reinventions of agile firms solely to visionary leadership – and Kongō was ruthless in its approach to succession, passing over eldest sons for more effective sons-in-law when required – they depend just as much on organisation-level capabilities such as these.

Doing so may not guarantee you’ll last a thousand years or more like Kongō Gumi, but it will at least give you a fighting chance of making it to the next century, through all the profound changes that will entail.

What will you be remembered for? How will you create progress in your business and society, and leave your world a better place for those who follow you?

There is a huge clock ticking deep inside a Texas mountain. It is hundreds of feet tall, and designed to tick for 10,000 years.

Every once in a while the bells chime, each time playing a melody that has never been played before, programmed not to repeat themselves over the ten millennia. It is powered the energy created through temperature fluctuations between day and night.

The clock is real, an art instillation inside a mountain in western Texas, funded by Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, and managed by the Long Now Foundation, a non-profit organisation.

Bezos contributed $42 million to the project, and hopes the clock will be the first of many millennial clocks to be built around the world over the coming years. A second location has already been purchased at the top of a mountain in the middle of a Nevada forest.

Ten thousand years is about the age of civilization, so the 10,000 Year Clock represents a future of civilization equal to its past. For Jeff Bezos it is symbolic of our need to protect and nourish our planet for the long term. He calls it his legacy, and sits alongside his $10 billion Earth Fund which he launched in 2020, as his contribution to the future.

What will you give to the future?

Legacy is one of the most motivating topics for business leaders. What will you leave behind? What is your contribution to others that follow you?

We are so wrapped up in our current world. Trying to deliver performance, trying to accelerate growth, trying to transform our business to take it to a better place, that we spare few moments to ask what would we leave behind.

Not just a memory. Not just a reputation. But a contribution to the future.

One of the most memorable books I ever read was Randy Komisar’s “The Monk and the Riddle”.

In 2003, having just taken on the role of CEO of a mid-size organisation, I wanted to give my 100 top managers some food for thought. Yes, we could develop new strategies and organisation change, but firstly I wanted them to think bigger, about the future, and what we could be, and what they themselves could be. I gave each of them a copy of the book.

It starts with a monk on a motorbike driving off into the desert, and then returning back to where he began. Asked where he has been, he answers that he has been on a journey. Sounding like a zen-like philosophy, many would give up at this point, but given that it was published by Harvard Business School, I persisted.

Komisar is a Silicon Valley technology legend and now a partner at Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers. He thinks you should look for more in your business career.

He reflects on the number of colleagues and friends he has known in tech start-ups who have pursued their ideas, working relentlessly, and all they think about is the exit strategy. He suggests this is not fulfilment. Yes, they might end up wealthier, but have they really achieved what they want in their lives?

“Passion and drive are not the same at all. Passion pulls you toward something you cannot resist. Drive pushes you toward something you feel compelled or obligated to do. If you know nothing about yourself, you can’t tell the difference. Once you gain a modicum of self-knowledge, you can express your passion. It’s not about jumping through someone else’s hoops. That’s drive” says Komisar.

Most people have a dream, and most often the dream is not to simply makes lots of money, but to achieve something. Achieving something is usually quantified by making a difference to the world. This might be achieved through a business route, leveraging the power of brands and consumption, finance and resources, to make a difference to the world. Or it might be in less commercial ways. However most leaders, according Komisar, defer this for a later act, to do once they’ve delivered on their initial business, once they’ve retired maybe. He calls it “the deferred life plan”. We have dreams, but we defer them for a later day.

The real passion we have for life, for achieving our life plan, shouldn’t be something we defer for another time, when we might not even be fit enough to achieve it, but be part of now. Embracing it within what we do, our job today. Leading our business to achieve both business and personal aspirations.

There is an echo of this in “The Second Mountain” by David Brook.

Brook says that every so often, we meet people who radiate energy and joy, who seem to “glow with an inner light”. Life, for these people, has often followed what we might think of as a two-mountain shape. They leave school, start a career, and they begin climbing the career mountain they thought they were meant to climb.

Their goals on this first mountain are the ones our culture endorses – to seek business success, to make your mark. But when they get to the top of that mountain, something happens. They look around and find the view unsatisfying. They realise that this wasn’t their mountain after all, and that there’s another, bigger mountain out there that really is their mountain.

And so they embark on a new journey, on their second mountain, and their life moves from self-centred to others-centred. They want the things that are truly worth wanting, not the things other people tell them to want. They embrace interdependence, not independence. The difficulty, however, is that most people only find their second mountain when they retire, and then it is often too late.

Your legacy is not what you have done, it’s what you give to the future.

How will you create a better world?

In writing my most recent book Business Recoded I explored the shifts in business, from today to tomorrow, from profit to purpose, with more meaning and impact.

This is legacy. Legacy is not creating a legend, its creating a contribution to the future.

I truly believe that business can be a platform for change in our world, but also a platform for good. And that you can achieve more in business, by doing good at the same time.

The best opportunities often arise out of seemingly unsurmountable challenges, you might call them paradoxes which seem unable to resolve contradictory goals. Apparent paradoxes, at least through our existing lens, offer business leaders new spaces to explore, new ways in which business can make a difference, by combining its huge resources for more positive impact.

Here are 15 big questions for business, and the world:

- Climate: How can economies grow, whilst also addressing climate change?

The last two decades have been the warmest on record. Whilst growth in CO2 emissions has slowed due to efficiencies and renewables, the earth is still warming. The Paris Agreement seeks a 1.5°C cap above pre-industrial levels.

- Resources: How can population growth and resources be brought into balance?

Global population will grow to 9.8 billion by 2050. If all are to be fed, then food production will have to increase by over 50%, while urban residential areas are expected to triple in size by 2030.

- Technology: How can new technologies, like AI and robotics, work for everyone?

51% of the world is now connected to the Internet. About two-thirds of the people in the world have a mobile phone. The continued development and proliferation of smart phone apps are AI systems in the palm of many hands around the world.

- Women: How can the changing status of women help improve society?

Empowerment of women has been a key driver of social change over the past century. Gender equity is guaranteed by the constitution of 84% of the world’s nations, while “the international women’s bill of rights” is agreed by almost all.

- Disease: How can the threat and impact of new diseases, like Covid-19, be reduced?

Global health continues to improve, life expectancy at birth increased globally from 46 years in 1950 to 67 years in 2010 and 71.5 years in 2015. Total deaths from infectious disease fell from 25% in 1998 to 16% in 2015.

- Energy: How can our growing energy demands by met efficiently and responsibly?

In China is the biggest producer of solar energy, and its investing huge amounts in other water and wind power too. Meanwhile, a billion people (15% of the world) do not have access to electricity.

- Water: How can everyone on the planet have sufficient clean water?

Over 90% of the world now has access to improved drinking water, up from 76% in 1990. That is an improvement for 2.3 billion people in less than 20 years. However, that still leaves almost a billion people without access.

- Conflict: How can shared values and security reduce conflicts and terrorism?

The vast majority of the world is living in peace, however, the nature of warfare and security has morphed today into transnational and local terrorism, international intervention into civil wars, cyber and information warfare.

- Crime: How can organised crime be stopped from becoming more powerful?

Organised crime accounts for over $3 trillion per year, which is twice all military annual budgets combined. It is estimated the value of black market trade in 50 categories from 91 countries is $1.8 trillion.

- Democracy: How can genuine democracy emerge from authoritarian regimes?

105 countries are experiencing a net decline in freedom, according to Freedom House think tank, while 61 are improving in net freedom, 67 countries declined in political rights and civil liberties, whilst 36 registered gains.

- Inequality: How can economies reduce the gap between rich and poor?

Extreme poverty fell from 51% in 1981 to 13% in 2012 and less than 10% today,mostly due to income growth in China and India. However the wealth gap is increasing, 1% have more than 99%, 8 billionaires have more than 3.6 billion people.

- Education: How can we better educate humanity to address global challenges?

Alphabet and others seek everyone on the planet connected to the Internet. The price of laptops and smart phones continues to fall, and IoT with data analytics gives real-time precision intelligence. However, successfully applying all these resources to develop wisdom, not just more information, is a huge challenge.

- Progress: How can tech breakthroughs accelerate to address our big challenges?

IBM’s Watson already diagnoses cancer better than doctors, Organova can 3D print human organs including new hearts, robots learn to walk faster than toddlers, and AlphaGo outsmarts the smartest humans. In 2020 China had 40% of all robots in the world, up from 27% in 2015.

- Ethics: How can ethical considerations by incorporated into global decisions?

Decisions are increasingly made by AI, who’s ethics are shaped by algorithms without conscience or control. Ethics are also influenced by manipulated information, by “fake news”, and political exaggeration, that can distort perceptions, leading us to wonder what is the truth, and who can we trust.

- Foresight: How can we make better future decisions with so much uncertainty?

Although the most significant of the world’s challenges and solutions are global in nature, global foresight and decision making systems are rarely employed, leaving the world’s best brains disconnected. Global governance systems are not keeping up with growing global interdependence.

These are not questions just for the United Nations, or governments or intellectual think tanks. These are questions for you, business leaders who have the power and platforms to make a real difference. So what could you do?

Letter to the future

What would you write in a letter to your grandchildren?

Talking to Richard Branson about his life seemed like an endless tail of intrepid adventures. We talked about his successes in music and airlines, and his passions for hot air ballooning and kitesurfing. He said he was much more interested in the future than the past, He became particularly animated when we got onto space, the potential for anyone to become an astronaut within his own lifetime. And the future potential of technologies to allow us to do amazing things, that are also better for humanity.

He told me that he wanted to write a letter to his grandchildren, Artie, Etta and Eva-Deia, about his hopes for them and their future. He recently published his letter on his blog, from which here is an extract:

“You are at the very start of life, it is an incredible gift and it is there for the taking. It will deliver highs and lows, trials and tribulations, failures and triumphs. But by living it to the full, by always trying to do the right thing and by never losing that sense of adventure which you now posses with such abundance, it will indeed be wonderful.”

“My golden rule in life is to have fun. Life is not a dress rehearsal, so don’t waste your precious time doing things that don’t light your fire. Do what you enjoy, and enjoy what you do. Trust me; great things will follow.”

“Don’t let your head always rule your heart. Life’s more fun when you say yes – so dream big and say yes to your heart’s desires. Dreaming is one of our greatest gifts – so look at the world with wide-eyed enthusiasm, and believe you are more powerful than the problems that confront you.”

“Never betray your dreams for the sake of fitting in. Instead be passionate about them. Passion will help you stay the course, and inspire others to believe in you and your dreams too.”

“Remember to treat others like you would like to be treated. Always be nice, always be caring. Give people the benefit of the doubt. And don’t hesitate to give out second chances. It’s incredible how much people lift and rise to the challenge when you believe in them and trust them.”

“Be open with everyone around you, especially your parents. They will always be there for you, willing to share in your adventures, support your decisions and love you unreservedly.”

“Above all, love and know that you are loved. Love always, Your grand-dude.”

Tech is the shiny new thing.

In most executive teams, AI is talked about in hushed tones. We all know it matters, not entirely how. Marketers will arrive with grand plans for their brand metaverses, or super-apps, while chatbots and more apps are seen as the answer to customer service woes. Add in a few ventures, and we can change the world.

Tech is certainly a driving force of change. But beware of the shiny new thing!

Most innovation in recent years has come by thinking differently, in particular by reengineering business models in response to changing customer agendas, or new emerging segments. Think about the low-cost airlines, in many cases trumping the full service giants. Love or hate it, Ryanair is now the most valuable airline in the world.

The latest tech is exciting. But do customers really want it? Is it too soon? What’s the real problem to solve?

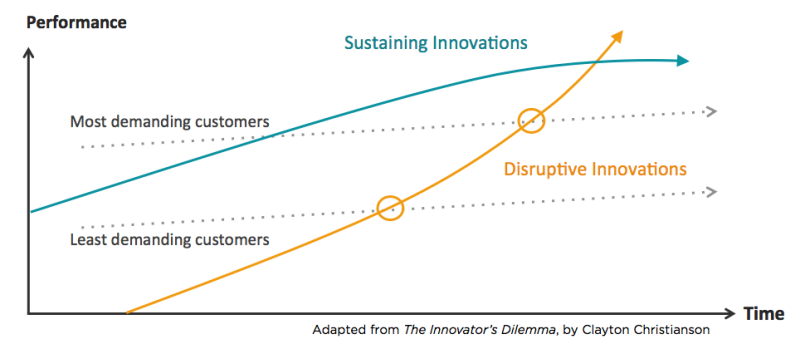

The Innovator’s Dilemma by the late, great, Harvard Business School professor Clayton Christensen, is one of the classic business books of our time. He wrote the bestselling text in 1997, but it it is still valuable today.

The book explains how successful companies that dominate their industries fail in the face of disruptive innovation. It’s a message of caution for leadership teams at these companies, but also a message of encouragement for competitors venturing against these goliaths.

Here’s a great 4 min video which summarises the book.

First, it distinguishes between sustaining and disruptive innovation. Then, it discusses why it’s difficult for most companies to adopt disruptive technologies. And finally, it considers what does it all mean for both large companies and startups.

In all of this, there is one important term that needs to be clarified. Christensen famously coined the word “disruption” which deserves some prior explanation due to its overuse in the media.

Here is an excerpt from the book to hopefully clear things up:

“Most new technologies foster improved product performance. I call these sustaining technologies. Some sustaining technologies can be discontinuous or radical in character, while others are of an incremental nature.

What all sustaining technologies have in common is that they improve the performance of established products, along the dimensions of performance that mainstream customers in major markets have historically valued.

Most technological advances in a given industry are sustaining in character. An important finding revealed in this book is that rarely have even the most radically difficult sustaining technologies precipitated the failure of leading firms.

Occasionally, however, disruptive technologies emerge: technologies that result in worse product performance, at least in the near-term. Ironically, in each of the instances studied in this book, it was disruptive technology that precipitated the leading firms’ failure.

Products based on disruptive technologies are typically cheaper, simpler, smaller, and, frequently, more convenient to use. There are many examples in addition to the personal desktop computer and discount retailing examples cited above. Small off-road motorcycles introduced in North America and Europe by Honda, Kawasaki, and Yamaha were disruptive technologies relative to the powerful, over-the-road cycles made by Harley-Davidson and BMW. Transistors were disruptive technologies relative to vacuum tubes. Health maintenance organizations were disruptive technologies to conventional health insurers. In the near future, “internet appliances” may become disruptive technologies to suppliers of personal computer hardware and software.”

It’s also important to understand the difference between radical sustained innovation and disruptive innovation as explained above. Often, the media will be quick to incorrectly dub a case of sustained innovation as being disruptive. The key difference is that the value network of a disruptive technology is distinct to the market offering at the time.

The innovator’s dilemma is that in every company there is a disincentive to go after new markets. Competent managers in established companies are faced with the question: “Should we make better products to make better profits or make worse profits for people that are not our customers that eat into our own margins?”. Paradoxically, this will doom companies in the long run.

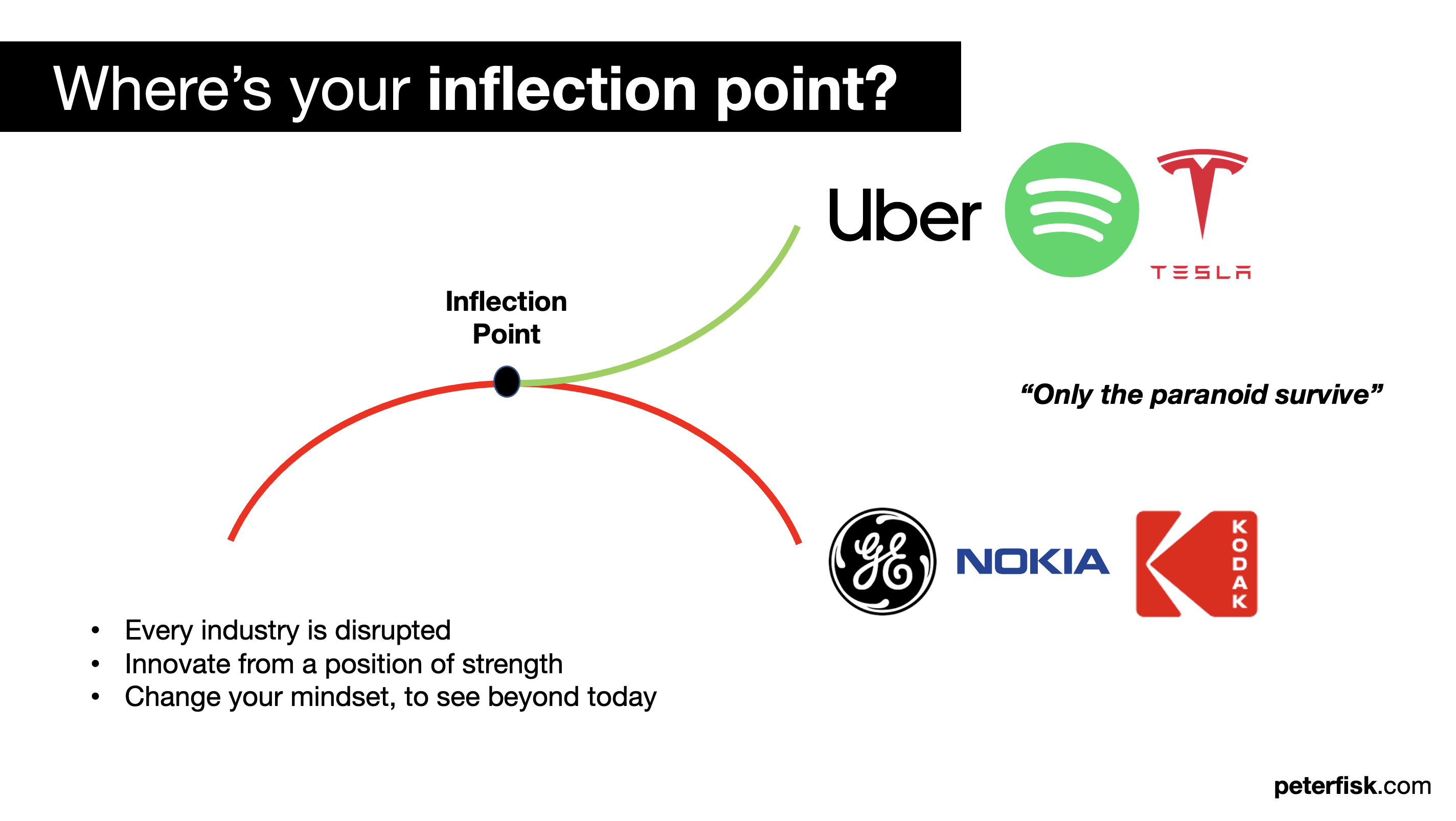

Evidence shows that the longevity of companies is decreasing as the pace of technological advances increases.

Here’s Clay Christensen in 2016, (he sadly died in 2020), taking his ideas further:

A gentle breeze cools the hot sunshine. The cypress trees sway, but the blue sky looks serene. In the distance, the volcanic cone of Vesuvius looms mistakenly beautiful.

This week I’m in Italy, and taking a few days off to explore the incredible Roman city of Pompeii.

We are all familiar with the story. Indeed, as a child I always thought of it as one of those classical legends, but as I grew older I realised it was real.

Largely preserved under the 4-5m of volcanic ash, the excavated city offers a unique snapshot of Roman life, frozen at the moment it was buried. It was a wealthy town, with a population of 11,000 in AD 79, enjoying many fine public buildings and luxurious private villas with lavish decorations, furnishings and works of art. Beautiful courtyards at the heart of wealthy family homes, fast-food stalls serving the many sea-faring visitors, even a brothel with a graphical menu of services.

Organic remains, including wooden objects and human bodies, were interred in the ash. Over time, they decayed, leaving voids that archaeologists found could be used as moulds to make plaster casts of unique, and often gruesome, figures in their final moments of life. The numerous graffiti carved on the walls and inside rooms provide a wealth of examples of the largely lost “vulgar” latin spoken colloquially at the time, contrasting with the formal language of the classical writers.

As you explore the endless stone-cobbled, well-preserved streets, it is obvious that there was great opulence in the city. The city’s people clearly took pride in showing off their immense wealth. The prosperity of Pompeii was a key reason for its prominence back in the day, built on a strong economic foundation that was served by fertile grounds and an excellent geographical location. The lava terracing around the city gave it a security advantage, and the volcanic soil allowed flourishing agriculture.

As I walked around the deserted, but largely intact streets, I couldn’t help think about that day. When the volcano erupted. And within hours, the city was no more.

In spite of its desirable position, and great wealth, the city was engulfed by a massive volcanic explosion. One fateful morning, in 79 AD, the population met a tragic end in just a few hours. As lava ashes fell on the city, the population perished. Some were running away from the ashes while others were buried in their own homes. None of the great wealth, opulence, and superior vantage point could prevent the tragedy that stuck them.

Pompeii is a tragic reminder of the ephemeral nature of life.

In today’s business world, companies are not supposed to be transitory. They are expected to outlast the mortals that build them. When Tom Peters wrote In Search Of Excellence, he sang the praises of companies like Atari and GE. Where are they today? Remember MySpace or SecondLife? These organisations prided themselves on their quality of management, how they were shaping the future of markets, and should be worthy investments.

Or consider the threat of tsunamis across the vulnerable Pacific rim? Or the rising oceans threatening the Maldives?

Was the outcome in Pompeii ever preventable or should we just accept death as a part of natural events? Did the city’s leaders consider the risks of the nearby mountain, even in the days before, as smoke billowed out of the summit? Did they consider the risks? Did they have early warning systems, and escape plans? Or did they live in ignorance?

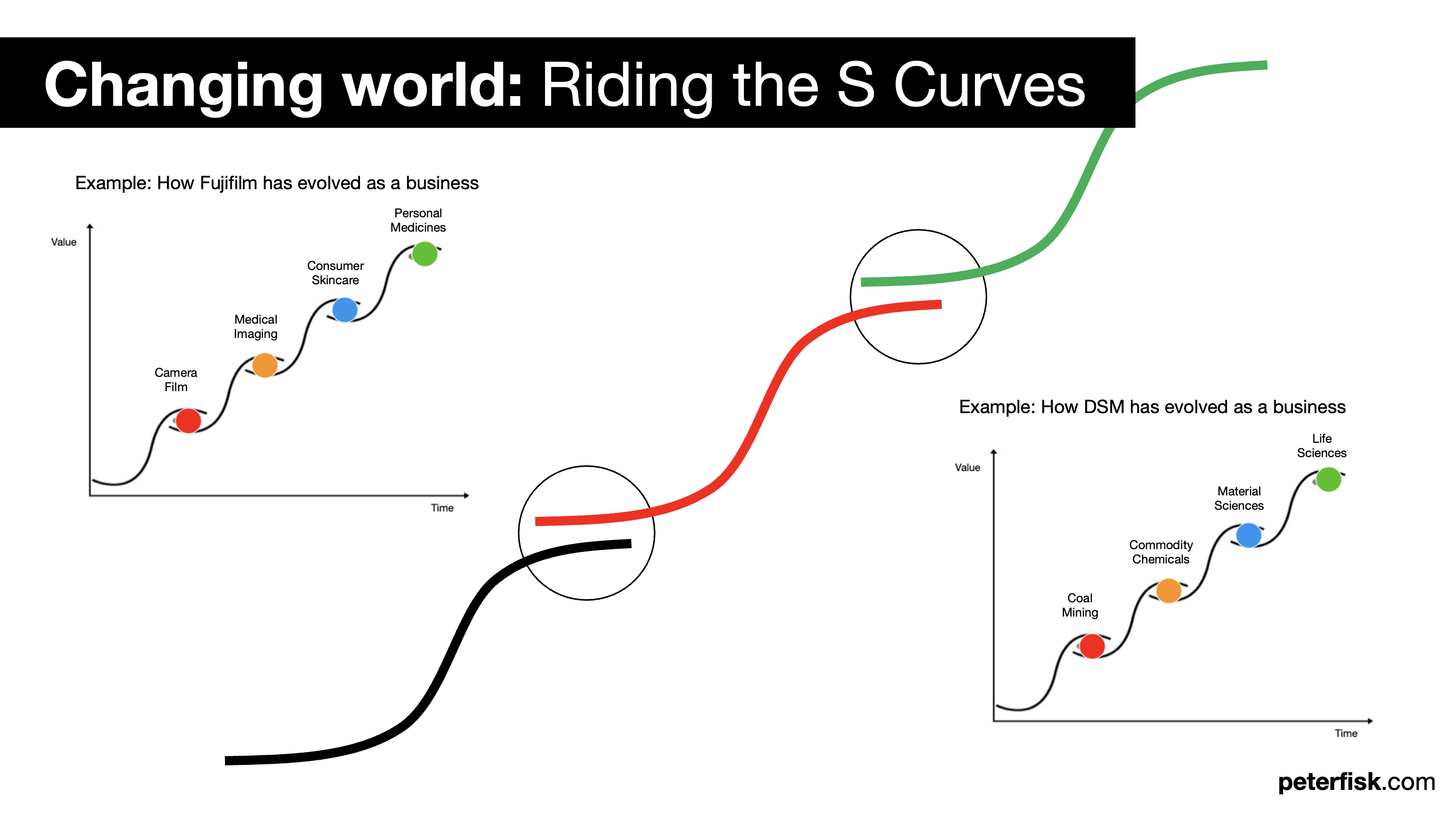

The challenge for every organisation today is, however prosperous their current environment might seem, there is always a Vesuvius on the horizon. Maybe a new entrant, a disruptive technology, or changing regulation. Something that can fundamentally transform the current world. Most often it will be visible but not directly threatening, coming from an adjacent or emerging market for example, already embraced by early adopters or extreme users, perhaps.

I work with many organisations – their boards, their exec teams, their strategists – on making sense of their future direction. How will they continue to innovate, to create and sustain profitable growth? How do they address the changing nature of markets, from climate change to digital platforms, changing consumers and new competition?

Most of the time, they are fixed within the mindset of optimising performance within their currently defined markets. It’s not easy to imagine how markets themselves will change, could be disrupted from beyond the current paradigms, or indeed how the companies themselves could proactively reshape markets, the nature of their business, and sources of value and advantage.

“S Curves” are a simple visualisation of these changing environments, and how companies can both create and respond to the relentless macro-waves of change. Consider the history of Dutch life sciences business DSM, or Japan’s Fujifilm, that have evolved far beyond their respective worlds of coal mining and camera film. Every market is constantly evolving, every company is constantly riding an S curve of change.

The challenge is then to change before you have to. Get to the top of the S curve and decline will probably already have set in – Vesuvius is already exploding – and it might be too late to change, as customers have already deserted you, and alternatives have already grabbed the future. The time to change is when times are still good, from a position of strength – part way up the curve – and when you still have time to move to your future market space, to create your future business.

It’s not easy, of course. Few of the Kodaks, Intels and GEs of the world were able to reinvent themselves. Largely because their mindset was locked into enjoying their current successes, and a mistaken belief that what got them this far, will take them further. But it rarely does. And so a new generation of companies like Spotify and Tesla reinvented their worlds.

As I walked around those Pompeii streets. A historic civilisation frozen in time. How good is your early warning system? As markets will inevitably change, how will you change before you have to?

In 2022, the Crocs Classic Clog was the best-selling item of clothing on Amazon, the brand was one of the fastest growing brands in the USA, and global net revenues had grown to $3.6 billion. Crocs were spotted on high-fashion runways, collaborating with luxury brands like Balenciaga, and on the feet of celebrities such as Justin Bieber. GenZ, in particular, loved Crocs.

Compare that to the brand just 10 years earlier. Crocs shoes were endlessly mocked for their ugly appearance, and the company was on the brink of bankruptcy.

So how did Crocs revitalise itself? Through the power of community. Tapping into what made it distinctive, in some ways its ugliness, using the power of social platforms to become the brand of choice for many different tribes – whether you’re on the beach, or loving sports, working in hospitals, or gone fishing. Being relevant, and being “one of a kind“.

Networks Effects:

From brand communities to retail franchises and business ecosystems

“Network effects” typically account for 70% of the value of digitally-related companies. And for the speed of their growth.

But they are not just about technology, digital platforms and social media. The value of networks is not in how many store you have, or partners you have, or customers you have. But in how well you connect them.

Building and unlocking the value of these connections is the real secret.

Network effects were popularised by Robert Metcalfe, the co-founder of 3Com which created networking cards that plugged into a computer giving it access to the Ethernet, a local network of shared resources like printers, storage and the Internet.

Metcalfe explained that whilst the cost of the network was directly proportional to the number of cards, the value of the network was proportional to the square of the number of users. Or in other words, the value was due to the connectivity between users, enabling them to work together and achieve more than they could alone.

“Metcalfe’s Law” says that a network’s value is proportional to the square of the number of nodes in the network. The end nodes can be computers, servers and simply users. For example, if a network has 10 nodes, its inherent value is 100 (10×10=100). Add one more node, and the value is 121. Add another and the value jumps to 144. Non-linear, exponential, growth.

Network effects have become an essential component of a successful digital businesses. First, the Internet itself has become a facilitator for network effects. As it becomes less and less expensive to connect users on platforms, those able to attract them in mass become extremely valuable over time. Also, network effects facilitate scale. As digital businesses and platforms scale, they gain a competitive advantage, as they control more of a market. Third, network effects create a competitive advantage.

This is not about the technology itself, it is about how the technology enables networks to work – how they enable people to connect with each other, to collaborate and influence, to build mutual affinity and trust. Communities emerge and where the power of peer to peer influence is the primary source of trust, recommendation and sales.

Movements are a step even further in making networks work, giving them purpose, values and momentum. This might sound obvious. But think how many retailers do nothing to connect their consumers, particularly those with similar interests. Even telecom brands, with billions of users, do almost nothing to add value beyond the basic connections it provides.

In 2015, three Chinese academics – Zhang, Liu and Xu – tested Metcalfe’s Law based on data from Tencent and Facebook. Their work showed that Metcalfe’s law held for both, despite the difference in audiences and services. They also look at every $1 billion “unicorn” business that has grown over the last 25 years. They estimated that 35% of the companies had network effects at their core, however these network effects typically added up to 68% of the total value.

Linear business vs. network business

Linear businesses traditionally gained a competitive advantage by buying assets, controlling supply chains, and driving transactions.

Network business gain competitive advantages through the multiplying effect of the networks, and crucially what happens within its connections, relationships and interactions. Network-based business typically work much more collaboratively with customers and business partners, evolving into ecosystems that reach across traditional sector boundaries and can do much more.

As the network grows, its value multiplies. Think of a dating app. Initially a few users is very limiting, but as soon as the network grows, the opportunities to find a suitable match grow much faster. The value of the network to the user is in the number of connections possible, and for the business, the commercial value becomes the data that is generated through user to user interactions. This data can be captured and analysed, to drive more interactions between people, and becomes the real advantage. Jim Collins famously termed this the “flywheel effect”, for example, where more customers creates a better experience, whose reviews attract more customers, who reduce costs or increase advertising incomes, which enables lowers costs which attracts more customers.

Network effects, relationships and data, become the assets of a network-based business. They are “light” assets, typically in the form of intellectual property (compared to primarily heavy assets of linear companies), and drive “intangible” value financially.

There is a downside to network effects, in that exponentially growing networks become harder to control, coordinate or curate. The rise of unsolicited emails, fraudsters and fake news is one obvious consequence. And whilst Facebook and other networks employ huge armies of people to try to eliminate such factors, this is probably an old way of thinking. In reality it needs to leverage network-based solutions, such as peer to peer accreditation, as in the trust profiles which users give each other on platforms such as Airbnb, eBay and Uber.

15 types of network effects

As a starting point, network effects can be direct or indirect.

- Direct (same-side, or symmetric) network effects happen when an increase in users directly creates more utility for all of the users, that is, a better product or service. Consider, for example Facebook or Tinder.

- Indirect (cross-side, or asymmetric) network effects happen when an increase in users indirectly create more utility for other types of users. Airbnb and Uber, where more hosts and drivers creates more utility for guests and passengers.

Different business models encourage different network effects. Dynamic pricing, for example, is used by Uber to encourage more drivers to join the network when demand is high, or more passengers when demand is low.

Many varieties of network effects emerge, depending on the types of business, each with strengths and weaknesses. Here is are 15 types, where the first 5 of direct effects, the others indirect:

- Physical – infrastructure, typically utilities (eg roads, landlines, electricity)

- Protocol – a common standard for operating (eg Ethernet, Bitcoin, VHS)

- Personal Utility – built on personal identities (eg WhatsApp, Slack, WeChat)

- Personal – built on personal reputation (eg Facebook, Instagram, Twitter)

- Market Network – adds purpose and transactions (eg Houzz, AngelList)

- Marketplace – enables exchanges between buyers and sellers (eg eBay, Visa, Etsy)

- Platform – adds value to the exchange of a marketplace (eg iOS, Nintendo, Twitch)

- Asymptotic Marketplace – effect depends on scale (eg Uber, OpenTable)

- Data – data generated through use enhances utility (eg Google, Waze, IMDB)

- Tech Performance … service gets better with more users (eg BitTorrent, Skype)

- Language … a brand name defines a market or activity (eg Google, Uber, Xerox)

- Belief … network grows based on a shared belief (eg stock market, religions)

- Bandwagon … driven by social pressure of fear of missing out (eg Apple, Slack)

- Community … driven by shared passion and activity (eg ParkRun, Harley Owners)

- Movement … driven by shared purpose or protest (eg Occupy, Black Lives Matter)

Most iPhone apps rely heavily on the existence of strong network effects. This enables the software to grow in popularity very quickly and spread to a large userbase with very limited marketing. The “freemium” business model has evolved to take advantage of these network effects by releasing a free version that affects many users and then charges for “premium” features as the primary source of revenue.

eBay would not be a particularly useful site if auctions were not competitive. As the number of users grows on eBay, auctions grow more competitive, pushing up the prices of bids on items. This makes it more worthwhile to sell on eBay and brings more sellers onto eBay, which drives prices down again as this increases supply, while bringing more people onto eBay because there are more things being sold that people want. Essentially, as the number of users of eBay grows, prices fall and supply increases, and more and more people find the site to be useful.

Stock exchanges feature a network effect. Market liquidity is a major determinant of transaction cost in the sale or purchase of a stock, as a bid–ask spread exists between the price at which a purchase can be done versus the price at which the sale of the same security can be done. As the number of buyers and sellers on an exchange increases, liquidity increases, and transaction costs decrease. This then attracts a larger number of buyers and sellers to the exchange.

© Peter Fisk 2023. Excerpt from his book Business Recoded.

Ingenuity is the quality of being clever, original, and inventive. Popular in the 1800s, and less so today, it also has a sense of nobility, of ingeniousness. It comes the French ingenieux or Latin ingenium referring to the mind or intellect.

Takashi Murakami is often called the next Andy Warhol, fusing high and low art, combining ideas from both Japan’s rich artistic heritage, and its vibrant consumer culture. But whilst the American icon created multi-million dollar works of art, Murakami is much more interested in creating everyday objects for everyone, from bubble gum and t-shirts to phone covers and limited-edition Louis Vuitton handbags.

He started in the traditions of Japan, then studied “Nihonga” art which is a combination of 19th century eastern and western styles but became distracted by the rise of anime and manga in Japanese eighties culture. He loved the modern styles which connected with people, and the issues and aspirations of today’s society. He was fascinated by what made iconic characters such as Hello Kitty and Mickey Mouse so popular and enduring.

Japan has a centuries long tradition of “flat” art, achieved with bold outlines, flat colouring, and a disregard for perspective, depth, and three-dimensionality. “Superflat” was a term Murakami started to use in 2001 and has evolved into one of modern art’s most active movements, combining the traditions flat art with anime and manga, taking components of high and low culture to defy categorisation. He says that he uses the style to also reflect what he sees as the flat, shallowness of consumer culture.

Today Murakami is a rock-star artist, highly aware of his image and brand, and an avid user of social media. He loves fame and commercialism. His business has been helped by collaborations with celebrities, creating animated music videos for Kanye West and designing sculptures with Pharrell Williams.

If “ingenuity” is about thinking and performing in a way that is original and inventive, it is a good descriptor of Murakami. He is inspired by both the past and the future create his own distinctive presence, to connect with and challenges his environment, embrace personal insight and opinion to defy conventions, and them his audience with him.

Imagination, creativity and innovation.

Imagination is often called the primary gift of human consciousness.

In a world of ubiquitous technology which challenges our humanity, a world of infinite yet largely derivative choices, and a world of noise and uncertainty, there is nothing quite like being human.

Imagination move us forwards. It allows us to leap beyond the conventions, the limits of our current world. It takes us beyond the algorithms of AI-enabled robots who can create perfection out of the world which they know, but struggle beyond it. It inspires us to think in new ways, to shape hypotheses to test, and aesthetic designs to enjoy.

Sir Ken Robinson is probably best known for his self-deprecating sense of humour with which he delivers a very important message: “Imagination is the source of all human achievement.” The Times said of his UK government report on creativity, education and the economy that “it raises some of the most important issues facing business in the 21st century. It should have every CEO thumping the table and demanding action.”

His book “Out of Our Minds: Learning to be Creative” argues that our world is the product of the ideas, beliefs and values of human imagination that have shaped it over centuries. He says, “the human mind is profoundly and uniquely creative, but too many people have no sense of their true talents.”

- Imagination explores new possibilities and captures them as new ideas

- Creativity shapes and stretches the potential of existing ideas

- Innovation takes existing ideas and makes them practical

Creativity is applied imagination, innovation is applied creativity, you could say.

I remember back to when my two daughters were young, the pictures they drew and models they built, the questions they asked and answers they imagined. There’s was a world unlimited by experience, by prejudice or conformity. Their brush strokes were simple, their colours bold, their questions were simple but disturbingly difficult.

As adults we shift to a productivity mindset, preferring to get things done, rather than explore possibilities. We seek to reduce complexity to its simplest form and describe ideas in the context of what we already know, squeezing out any nuggets of newness.

We are all born creative, but somehow lose that spark, or at the confidence to allow it out. Some people, we say, are creative, and others not. Yet we all have the same neurons and synapses which drive the process. The reality is that no individual is as creative as even the dullest people once they start working together. If we could reclaim our creativity, we could discover our passion, allowing us to feel more alive, and do so much more.

Harvard professor Howard Gardner identified 8 “intelligences” or ways to solve problems. They range from linguistics (limited only by the words you use), logical (mainly through mathematics), spatial (as used by designers), musical, physical (like athletes), natural (like farmers), intrapersonal (within yourself), and interpersonal (with others).

The point is that we have many ways to be creative, or even combinations of our mental and physical capabilities. As Leonardo da Vinci loved to say, inspired by his own polymath life as artist and musician, anatomist and sculptor, architect and engineer, creativity is ultimately about making new connections.

Innovation makes life better

The purpose of any business, and therefore any innovation, is to make life better. It drives human and social progress, as well as seizing new opportunities for business growth. Whilst it is a practical, technical and process-based challenge, it is also human and philosophical, strategic and futuristic.

The Royal Society of Arts recently published a document “How to be Ingenious” starting with a definition of ingenuity as having three components:

- an inclination to work with the resources easily to hand

- a knack for combining these resources in a surprising way

- and in doing so, an ability to solve some practical problem

Another way to describe it is the ability to do unexpectedly more for less in the face of constrained resources. Given the social and environmental challenges facing every business today, that might be a useful addition.

The Huit Denim Company is a great innovator for social good. Cardigan, a small town on the west coast of Wales, used to have Britain’s biggest jeans factory. It employed 400 people in a town of 4,000 people, making 35,000 pairs a week, but it closed suddenly in 2001. It had a huge effect on employment, but also on confidence in the town. David and Claire Hieatt responded by deciding that they would to try to get 400 people their jobs back. Huit Denim Co was born, and now with a cult global following. Their semi-automated, hand-stitched process still takes 5 times as long as most jeans factories, but they can then sell them online direct to consumer for $300 a pair, securing a profit margin that keeps the town in work again.

Navi Radjou, the French-Indian author of Frugal Innovation likes to remind me that some of the most ingenious ideas comes from emerging markets, where people improvise to solve problems. He tells the story of Kenyan villager Peter Kahugu, for example, who used a set of pulleys, a sharpening stone and an inner tube to modify his bicycle. Re-using the inner tube as a rubber belt, he created a pedal-powered knife-sharpening service and earns about $10 a day.

A more inspired approach to innovation

Innovation demands human ingenuity.

It is exciting, it is about people, about the future, with limitless possibilities.

It is an essential role of every business leader, every business function. Whilst innovation has long centred around the tangible, technical icon of the product, organisations have finally opened their minds to many more forms of innovation.

Innovation used to be associated with long, disciplined, stage-gated processes by which ideas were productised and taken to market. Today’s innovators, in small and large businesses, get excited by design thinking and lean development. These are useful tools to create more insightful and faster solutions, but there is much more to innovation.

A more inspired approach to innovation has 9 dimensions

- Human-centred rather than driven by products

- Problem-solving rather than limited by capability

- Future shaping rather than aligning with today

- Whole business rather than functionally isolated

- Fast and experimental rather than slow and perfect

- Sustainable impact rather than profit obsessed

- Active adaptation rather than launch and forgotten

- Growth driving rather than unaligned commercially

- Portfolio building rather than isolated innovations

Innovation is not like most other business functions and activities. There is no department or VP of innovation in most companies. There is rarely even an innovation strategy or budget. There are few standard templates, rules, processes, or consistent measures of success. In a sense, each act of innovation is a unique feat, a leap of imagination that can be neither predicted nor replicated. It is certainly not business as usual.

That’s also the beauty. Innovation is pervasive, a challenge for every function and person across the business. It can have process, but it can also break all the rules, and sometimes needs to. By being rooted in every part of the business, and drawing on budgets from each, it can be a more collaborative, integrated and formidable approach.

Leaders are the ultimate innovators in companies, not necessarily entrepreneurs as in the founders of start-ups, but setting the agenda, ensuring that it has the resources and space to thrive, and that the business delivers today, but also creates a better tomorrow.

© Peter Fisk 2023.

Excerpt from “Business Recoded” by Peter Fisk

Markus Villig was a teen-tech entrepreneur, launching his startup as a 19 year old, in the same year he graduated from his Tallinn high school. He went on to become the youngest founder of a European billion-dollar company.

Bolt, then known as Taxify, launched in the Estonian capital promising to take lower commissions – which meant higher net wages for drivers, and lower fares for passengers, compared with other ride-hailing apps, like Uber. In fact I remember landing on an Air Baltic flight in Tallinn, and all business travellers had a direct connection to the Taxify cars waiting outside.

In 2019, Taxify rebranded as Bolt and is now one of the world’s fastest-growing mobility platforms, offering ride-hailing, car-sharing, food-delivery, and electric-scooter services to more than 100 million customers in over 45 countries.

While Uber, the world’s leading ride-sharing business, was blowing billions of dollars trying to buy global domination, Markus Villig was busy doing the opposite with Bolt. The Estonian, working on a relatively small budget, has built a $8.4 billion business, and an $700 million personal fortune, by focusing on overlooked markets in Africa and Europe.

Between 2015 and 2019, Villig scaled up Bolt from $730,000 sales to $142 million. He couldn’t afford big losses, so he operated the company close to break-even. Uber, by contrast, burned through $19.8 billion, almost $6.3 million a day, before going public in 2019.

Villig’s careful approach has paid off. The business now has more than 3 million drivers, operates in 45 countries and generated $570 million in 2021 sales revenue. At its latest valuation, in January 2022, the company was said to be worth $8.4 billion. Of course, startup values have since tumbled, and with a 20% stake, the 29-year-old Villig is now Europe’s youngest billionaire.

Villig knew he wanted to start a tech company when he was as young as 12, according to a recent CNBC profile

At age 19, Villig dropped out of college after just one semester studying computer science at the University of Tartu, in Estonia, as his ride-hailing app, Taxify, began to take off. and the 25-year-old is the youngest founder of a billion-dollar company in Europe, according to research by Estonian start-up network Lift99.

Villig started the business with a 5,000 euro loan from his family to build a prototype of the app, the summer after graduating from high school. He was inspired by Skype, which was founded in his home country of Estonia in 2004, showing a technology business “could be launched from anywhere.”

“I realized that tech is one of those industries where you can have huge leverage in the fact that you can accomplish big things with a very small team,” he told CNBC. And even as interest in the app started to pick up, Villig said he remained disciplined with business costs by avoiding “hiring loads of people or doing expensive marketing campaigns.”

In fact, Villig took to the streets himself in Estonia’s capital Tallinn to recruit taxi drivers in the early days of the business “Ultimately it comes down to being extremely customer focused and frugal,” he said. “This is an industry where customers really care if they get good value for their money,” he adds. “So if you can offer customers 20% better pricing or you can make sure the drivers take 20% more on every ride then that really pays.”

Bolt drivers can earn over 10% more on average compared to other ride-hailing platforms, as it takes 15% commission from them per ride, compared to the 25% Uber charges it “partners” on each fare.

Yancey Strickler, the Kickstarter founder, makes a passionate argument that we can, and must, redefine the measures of success if we want a stronger society than the one we have today.

He describes today’s business world as one of “crumbling infrastructure, the dominance of mega companies, and the rise of offshore tax havens.” He isn’t opposed to money, or even wealth. “If businesses were optimised for the community or sustainability” he says, “the rich would still be rich, just not as rich,” whilst the vast majority of people would be wealthier and happier.

In the global pandemic of 2020, the impact of a single-minded pursuit of profit was brought into sharp relief as the business world shut down and huge numbers of people lost jobs. The lack of healthcare provision and social safety nets plunged workers of all levels into turmoil. Similarly, hospitals lacked essential equipment because of a relentless drive for efficiency. As stock markets plunged, and trillions of dollars of value were wiped out, businesses started to realise the folly of their frugality and lack of compassion.

Business has sought to maximise financial performance for so long that it’s hard to imagine another reason for companies to exist.

Profitability and value creation.

Profits have become the predominant metric of success. Many people in business still think that market share and sales revenues are the goals, yet for some time we have seen that big is not always better. As customers and products have become less equal in their relative profitability, it is often more profitable to focus on less rather than more. Similarly, multiple channels with different efficiencies, and a drive to discounting, means that more sales don’t always convert into more profits.

The notion of “value” us important. Businesses are often defined as value exchanges, creating value for customers and capturing value for the business.

Economists evaluate businesses based on the sum of future profits, adjusted for how likely these profits are to emerge. Strong brands, relationships and innovation pipelines make future profits more certain. Their sum is known as the enterprise value, reflected externally on stock markets, based on the judgement of analysts and behaviours of investors, as market value. Executives are incentivised to deliver profits, however more thoughtful incentives will encourage their preference to sustain profits over time, often based around total shareholder return, the growth in market value plus a share of dividends.

Business leaders can decide how to design their value creation machine, in particular how to share value between all stakeholders over time.

As profits emerge each year, leaders decide how much to allocate to employees in salaries and bonuses or as improved conditions, how much to allocate to customers through innovative products and services or better prices, how much to allocate to investors in dividends or cash, and how much to share with society through social initiatives or more generally through taxation. The relative allocations, and for what, determine how effectively the business invests for its future, to sustain the creation of value – or in other words, to grow a larger “value pie”, from which everyone can enjoy a healthy share.

However, that ideology gets disrupted by greed, particularly by owners who are more interested in making a quick return, rather than seeing a sustainable long-term business.

James O’Toole is his book “The Enlightened Capitalists” explores the history of business leaders who have tried to combine the pursuit of profits with virtuous organisational practices – people like jeans maker Levi Strauss and the Body Shop’s Anita Roddick.

He tells the story of William Lever, the inventor of the Sunlight soap bar who created the most profitable company in Britain, the origins of today’s Unilever, and used his money to greatly improve the lives of his workers. In 1884 he bought 56 acres of land on the Wirral, near Liverpool, and built a new town for his workers, known as Port Sunlight, where workers and their families could live healthier and happier lives. Eventually, he lost control of the company to creditors who promptly terminated the enlightened practices he had initiated. The fate of many idealistic capitalists.

From shareholders to stakeholders

In recent years the relationship between business and society has become increasingly fractured. Whilst there is nothing wrong with shareholders, and nothing wrong with profits, the culture of capitalism seemed increasingly out of sync with the world. A series of economic, social and environmental crises made it all the more obvious.

Of course, most businesses have woken up to the importance of sustainable issues, and their responsibilities to society over recent years, but they have largely seen them as a new component of capitalism.

10 years ago, I wrote the book “People Planet Profit: How to embrace sustainability for innovation and growth” which sold many copies, but little seemed to change. Yes, we got the sustainability report as an appendix to the annual report, the foundation that operates at arms’ length from the core business, and a host of initiatives to reduce emissions and waste. At the same time, social enterprises emerged – indeed, I was a CEO of a $50 million non-profit business myself – but such organisations were still seen as a different breed from commercial businesses. Core business didn’t change.

And then three things happened.

- In January 2018, BlackRock’s Larry Fink wrote a letter to the CEOs of all the companies who he invests in, saying that he would not continue unless they could demonstrate that they will delivering on a significant “purpose before profit”. BlackRock is the world’s largest investment firm, a $6 trillion asset manager. This was seismic.

- In August 2019, The Business Roundtable, the most influential group of US business leaders said they would formally embrace stakeholder capitalism, built on “a broader, more complete view of corporate purpose, boards can focus on creating long-term value, better serving everyone – investors, employees, communities, suppliers and customers.”

- In January 2020, the World Economic Forum launched the Davos Manifesto for “a better kind of capitalism” saying “the purpose of a company is to engage all its stakeholders in shared and sustained value creation” with “a shared commitment to policies and decisions that strengthen the long-term prosperity of a company.”

Klaus Schwab, founder of WEF, called it “the funeral of shareholder capitalism”, but also as the bold and brave birth of stakeholder capitalism.

Marc Benioff of Salesforce added that “Capitalism as we know it is dead. This obsession with the pursuit of profits just for shareholders does not work”. IBM’s Gina Rometty said that there are now two types of business “good and bad”.

Jim Snabe of Maersk said, “companies need to start making the change right now, to the way they work, the resources they use, the taxes they pay, and the decisions they make.”

Smarter choices, positive impact.

The ideology sounds compelling. The challenge is to ensure that it changes how businesses work, the choices we make, and the impacts we have.

“Smarter choices” is the first challenge. A key role for the business leader is to make decision, yet this has become much harder of a complex world of many trade-offs. Strategy is also about choices, the directions and priorities for the business, short and long-term.

“Smart” lies in the ability to align the business purpose with all its stakeholders, and to find an effective way in which together they can sustain enlightened value creation.

“Positive impact” is the second challenge. Long have we heard the mantra, “what gets measured gets done”. Therefore, leaders need to underpin their stakeholder ideology with a new set of performance metrics, which drive behaviours, define progress, and rewards.

“Positive” lies in the ability for the business to create a “net positive” contribution to the world in which it exists, some of which will be financial, but also non-financial.

In particular, I get frustrated when people get excited about new zero. Yes of course, we want and need to dramatically reduce the carbon emissions of business. But net zero sounds like a terrible compromise, and indeed we see many carbon emitters still seeking to offset their badness by planting forests of trees, and claiming net zero as a success.

Positive impact is therefore about value creation. Creating more value for all stakeholders.

Not as a compromise or trade-off. Not the short-termist mindset that will seek more value for shareholders at the expense of customers (less innovation) or employees (lower salaries) or society (negative impacts).

This is not utopia. It comes by creating that bigger “value pie” and then each taking a fairer, larger slices of a bigger whole.

It comes through a long-term perspective – how business wins through amazing and well rewarded people, who develop and deliver incredible products and services for customers, who are happy to pay more for them and stay loyal, with less harm to the environment and more good for society, all producing more and more sustained returns for shareholders too.

And as a results a sustainable, virtuous circle of value creation emerges. Sustained, shared, superior value.

Performance metrics, making it happen.

All this sounds great. But what gets measured gets done.

Stakeholder capitalism desperately needs a set of metrics for sustainable value creation.

To seek a coherent model for this across the business and investment communities, the WEF brought 140 of the world’s largest companies together, supported by the four largest accounting firms – Deloitte, EY, KPMG and PwC.

Their starting point was to align the existing approaches to measuring Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) performance and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). They agreed to seek common metrics for greenhouse gas emissions and strategies, diversity, employee health and well-being as factors to publish in annual reports alongside financial metrics.

The proposed metrics and recommended disclosures have been organised into four pillars that are aligned with the SDGs and ESG domains. They are

- Principles of Governance, aligned with SDGs 12, 16 and 17, and focusing on a company’s commitment to ethics and societal benefit

- Planet, aligned with SDGs 6, 7, 12, 13, 14 and 15, and focusing on climate sustainability and environmental responsibility

- People, aligned with SDGs 1,3, 4, 5 and 10, and focusing on the roles human and social capital play in business

- Prosperity, aligned with SDGs 1, 8, 9 and 10, and focusing on business contributions to equitable, innovative growth.

There is some way to go in getting close to “integrated reporting”, and in particular connecting financial and non-financial metrics which enable the more difficult trade-off decisions, and to understand the genuine long-term health of an organisation.

One approach, developed by BCG, is Total Societal Impact (TSI) which is a defined basket of financial metrics and non-financial assessments, brought together as one overall score. This enables leaders to consider the relative overall impact of different strategic options.

The challenge of course, is that any private company’s total value will always be financial, as long as it is possible for a buyer to come along and pay a certain price for it.

A new value map for business

Deloitte recently proposed a new Sustainable Value Map for business that brings together:

- An ROI-based approach: To facilitate the consideration of what value creation looks like for each stakeholder group, the map provides baseline ROI frameworks for each. This approach provides two levels of drivers for both the ROI numerator (returns) and for the denominator (invested resources). Note that the frameworks represent illustrative starting points, informed by popular sustainability frameworks. We expect companies and their stakeholders to have their own views on the value drivers, and we propose that they work together to develop their own formulations.

- Linked ROI frameworks: To aid the determination of the “input/output” relationships between the value creation frameworks, the SVM also provides examples of potential resource and impact flows across stakeholder groups. The nature of these dependencies will vary by company, but this starting point can help jump-start a deeper understanding and articulation by leadership teams.

- A system view: To promote the orchestrated management of value creation across stakeholders the SVM puts the value frameworks and inputs/outputs on a single page. This makes it easier to avoid tunnel vision around any single stakeholder and also draws out the recognition of relationships and dependencies not always apparent in traditional analyses.

Boden, a small military town in northern Sweden is set to become Europe’s centre for green steel, with a new steel plant, 900 km north of Stockholm.

Steel is usually made in a process that starts with blast furnaces. Fed with coking coal and iron ore, they emit large quantities of carbon dioxide and contribute to global warming.

The production of steel is responsible for around 7% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions. But in Boden, the new plant will use hydrogen technology, designed to cut emissions by as much as 95%.

Although the first buildings have yet to go up on the remote site, the company behind the project, H2 Green Steel, believes it’s on course to roll out the first commercial batches of its steel by 2025.

If it succeeds, it will be the first large-scale green steel plant in Europe, with its products used in the same way as traditional steel, to construct everything from cars and cargo ships to buildings and bridges.

Although much of Europe’s steelmaking industry dates back centuries, H2 Green Steel is a start-up that didn’t even exist before the pandemic.

When Northvolt opened Sweden’s first giant electric battery factory two hours south of Boden, it wanted to find a greener way of producing the steel needed to make the batteries, and H2 Green Steel emerged as a spin-off with funding from two of Northvolt’s founders.

The centrepiece of the new steel plant will be a tall structure called a DRI tower (DRI means a direct reduction of iron). Inside this, hydrogen will react with iron ore to create a type of iron that can be used to make steel. Unlike coking coal, which results in carbon emissions, the by-product of the reaction in the DRI tower is water vapour.

All the hydrogen used at the new green steel plant will be made by H2Green Steel.

Water from a nearby river is passed through an electrolyser – a process which splits off the hydrogen from water molecules.

The electricity used to make the hydrogen and power the plant comes from local fossil-free energy sources, including hydropower from the nearby Lule river, as well as wind parks in the region.

“This a unique spot to start with. You have to have the space, and you have to have the green electricity,” says Ida-Linn Näzelius, vice president of environment and society at H2 Green Steel.

H2 Green Steel has already signed a deal with Spanish energy company Iberdrola to build a green steel plant powered by solar energy in the Iberian peninsula, and says it’s exploring other opportunities in Brazil.

On home soil it’s got friendly competition from another Swedish steel company, Hybrit, which is planning to open a similar fossil-free steel plant in northern Sweden by 2026. This firm is a joint venture for Nordic steel company SSAB, mining firm LKAB and energy company Vattenfall, boosted by state funding from the Swedish Energy Agency and the EU’s Innovation fund.

While Sweden is leading the way when it comes to carbon-cutting steel production in Europe, it is important to put its potential impact in context, says Katinka Lund Waagsaether, a senior policy advisor at the Brussels-based climate think tank E3G.

H2 Green Steel hopes to produce five million tonnes of green steel a year by 2030. Global annual production is currently around 2,000 million tonnes, according to figures from the World Steel Association.

“The production capacity in Sweden will be a drop in the sea,” says Ms Lund Waagsaether.

Other ventures should help increase the proportion of green steel available in Europe.

These include, GravitHy, which plans to open a hydrogen-based plant in France, in 2027. German steel giant Thyssenkrupp recently announced it aims to introduce carbon-neutral production at all its plants by 2045. Europe’s largest steelmaker ArcelorMittal and the Spanish government are also investing in green steel projects in northern Spain.

Meanwhile, the EU is in the process of finalising a new strategy called the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, designed to make it more expensive for European companies to import cheaper, non-green steel from other parts of the world.

“I think it is important in that it’ll give industry the confidence to invest, because they can see that, at least in the European context, their steel will be competitive,” says Ms Lund Waagsaether.

She also points to a “a crucial window of action” between now and 2030, with around 70% of steelworks around the world in need of repair and reinvestment during this period.

Blast furnaces could be replaced or relined to extend their lifetimes, but a smarter long-term strategy, argues Ms Lund Waagsaether, would be to invest in switching to carbon-cutting production processes instead.

“The next eight years are crucial for making sure that companies and investors globally make decisions towards green steel production… which is going to ‘lock us in’ for another few decades.”

But whether the majority of big steel producers will follow this path is difficult to predict, says Lundberg. “I would say I’m hopeful, but we need to keep the pressure up.”

In Boden, the arrival of H2 Green Steel is being viewed as a major opportunity for job creation in an area that’s been crying out for new industries for decades.

The small military town shrunk after army budget cuts and closure of a large hospital in the region in the 1990s, resulting in thousands of people moving elsewhere to find work.

“This is our biggest opportunity in more than 100 years,” says the town’s Social Democrat mayor Claes Nordmark. “This will mean jobs, it will mean more restaurants, it will bring more sponsorship to our football and ice hockey and handball team and so on. It means everything for us.”