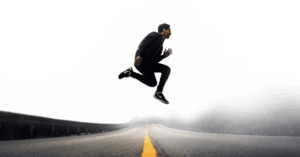

The Courageous Leap … Stepping up from manager to business leader sounds simple, but it requires a profound shift in mindset, capability, and behaviour

November 16, 2025

There comes a moment in every ambitious career when the familiar contours of the job begin to dissolve. The inbox is still full, the meetings still arrive with unrelenting regularity, but something feels subtly different. People look to you less for answers and more for direction. You begin to sense that decisions are no longer confined to the boundaries of your function; they ripple across teams, products, countries, and markets. The horizon, once comfortably contained within your remit, stretches disconcertingly far.

This is the moment where a person stands on the precipice of one of the most important transformations in professional life: the leap from manager to leader. For many, it arrives quietly. It is not heralded by grand announcements or new business cards. Rather, it is noticed in the sudden shift of weight on your shoulders, in the questions that now carry wider consequences, and in the dawning realisation that the skills that made you successful may no longer be enough.

The transition is often romanticised in leadership books and HR presentations, yet those who experience it know it as a deeply human pivot. It requires courage, not simply because the responsibilities multiply, but because the identity must evolve. A manager’s excellence lies in competence. A leader’s excellence lies in perspective, poise, purpose, and the ability to bring out the best in others. It is a profound change of role, mindset, and capability.

This article explores that change: the practical shift in responsibilities, the inner journey of mindset, the new capabilities demanded, and examples of European business leaders who have made this transition and articulated its impact.

From technical specialist to strategic generalist

Managers grow up through functional mastery. They become the best engineer in the department, the sharpest financial analyst, the most dependable operations supervisor. Their reputations are built on answers, speed, accuracy, and a deep familiarity with their craft.

But leadership does not reward expertise alone. Rather, it rewards the ability to mobilise many experts, to balance competing interests, and to build a view of the organisation that transcends any one part of it.

One of the clearest illustrations of this shift comes from Carsten Spohr, who moved from a technical and operational background to become the Chief Executive of Lufthansa. He has spoken often about the moment he realised that the airline could no longer be managed merely as an operationally excellent transport business; it had to be shaped as an interconnected ecosystem of brands, services, partnerships, talent, and long-term capability. His expertise in flying and operations was no longer the centre of his value. Instead, his value became the ability to interpret the future of aviation, navigate labour relations, digitalise the airline, and rebuild trust after crises.

The transition from functional to holistic thinking is not a simple widening of responsibility. It is a reconfiguration of identity. Leaders must become strategic generalists who think in systems rather than silos. This requires an ability to connect dots across markets, people, technology, and culture. It requires the humility to know what you do not know, and the willingness to surround yourself with those who complement your blind spots.

In many European organisations—often older, more complex, and more decentralised than their American counterparts—this shift is particularly pronounced. Leadership means orchestrating diversity: of countries, languages, regulatory regimes, and cultural expectations. The leader becomes not only a strategist, but a translator, mediator, and integrator.

From functional advocate to organisation champion

Managers understand success as the performance of their team. Leaders understand success as the strengthening of the entire enterprise.

This is one of the most difficult shifts to master, because it requires a loosening of emotional attachment to one’s own function. Where once you might have lobbied fiercely for more budget for your area, leadership requires recognising that the greater priority might lie elsewhere. The leader does not win by defending their territory, but by allocating resources where they create the greatest overall value.

Few have articulated this better than Emma Walmsley, Chief Executive of GSK, who stepped from managing a consumer-health division to leading one of Europe’s most complex pharmaceutical groups. She has described leadership as the discipline of thinking in decades rather than quarters, and the responsibility of making decisions not only for the areas she once knew intimately, but for the enterprise as a whole. Leading GSK meant breaking down silos between research, manufacturing, commercial teams, and external partners, and creating alignment across a company whose value rests not only in products but in science, talent, and reputation.

Enterprise leadership also requires wrestling with trade-offs. Sustainability versus profitability. Investment versus efficiency. Innovation versus risk. Leaders navigate these tensions by elevating their thinking beyond departmental performance, examining how the different parts of the business interplay, and shaping the organisational architecture needed for long-term success.

This shift is particularly visible in companies that are reimagining themselves for new realities. Nils Andersen, who rose through the ranks to become the leader of A.P. Moller–Maersk, speaks of the moment he recognised that the company’s future was not in managing ships, but in orchestrating global supply chains. The enterprise view transformed every decision: from digital strategy to capital allocation to the carbon transition.

From short-term deliverer to long-term value creator

Managers excel at delivering results. Leaders excel at creating value. The difference may seem subtle, but it is profound.

Short-term performance depends on control, efficiency, and meeting targets. Long-term value creation depends on building capabilities, cultures, platforms, and partnerships that allow an organisation to endure and evolve.

This shift demands patience and perspective. It requires the courage to invest in innovation, digital transformation, talent development, and sustainability even when the immediate financial returns are uncertain. It requires holding a steady course in the face of quarterly pressure, crisis, or ambiguity.

A compelling example comes from Hélène Rey, Chair of the Board at BNP Paribas, who has emphasised that leadership in modern organisations means stewarding the institution not merely for shareholders, but for society and future generations. In large European banks—often more regulated, more scrutinised, and more embedded in national ecosystems—the long-term view is not a luxury but a necessity.

Similarly, Frans van Houten, former CEO of Philips, led one of Europe’s most significant corporate transformations, shifting the company from diversified industrial conglomerate to focused health-technology leader. He has spoken about the discipline required to resist the gravitational pull of short-term earnings, instead investing in digital health, connected care, and organisational renewal. The leader became an architect of future value, not a caretaker of today’s results.

The Inner Shift: Leadership as a way of being

If the practical changes are visible, the psychological ones are far more subtle. Many new leaders describe the transition as an emotional unravelling, followed by a reconstruction of self.

A manager’s identity is often built around expertise, certainty, and action. A leader’s identity must be grounded in curiosity, humility, and influence.

Where managers gain confidence from knowing, leaders gain confidence from navigating the unknown. They must be comfortable being uncomfortable. They must be willing to ask questions rather than provide answers, to invite challenge rather than suppress dissent, to trust rather than direct.

Ilham Kadri, CEO of Syensqo and former CEO of Solvay, has spoken eloquently about this internal transition. Coming from a scientific and operational background, she realised that leadership meant shifting from problem-solving to possibility-shaping, from managing complexity to inspiring clarity, from proving her competence to amplifying the competence of everyone around her.

The psychological journey is not simply an expansion of responsibility; it is a reorientation of how one sees oneself in the world. The leader becomes a sense-maker, storyteller, and catalyst. They operate with a steadiness that others rely upon. They hold paradoxes without being paralysed by them. They create confidence not by providing certainty, but by offering direction and meaning.

The New Capabilities: What modern leaders must develop

The modern European leader requires a set of capabilities that are broader, deeper, and more multifaceted than ever before.

One is strategic acumen. This is not merely understanding strategy documents or market analysis; it is the ability to see patterns, connect ideas, and articulate a forward-looking narrative that gives the organisation coherence and purpose.

Another is enterprise thinking, the capacity to balance competing priorities, allocate resources wisely, and make decisions that strengthen the organisation as a whole.

A third is talent orchestration. Leadership today is less about managing people and more about mobilising them—connecting individuals with missions that energise them, building teams that blend skills and perspectives, and nurturing cultures where creativity and performance thrive.

A fourth is storytelling. In large, complex organisations spanning multiple markets and cultures, the leader’s narrative becomes the thread that aligns and inspires. It is through storytelling that leaders communicate priorities, express values, and create energy for change.

And, perhaps above all, leadership requires courage. Courage to confront uncomfortable truths. Courage to choose the long term over the expedient. Courage to take risks when the rewards are unclear. Courage to speak, to act, and to stand still when necessary.

This is not theatrical bravery. It is the everyday courage of staying true to a vision, of holding steady through criticism, of leading in ambiguity, and of trusting others.

What the transition feels like

Leaders often speak of a disconcerting period where the old certainties dissolve but the new ones have not yet appeared. This is a natural part of the evolution.

- You lose the comfort of expertise, because leadership demands that you make decisions far outside your technical domain.

- You become more visible, because people read every gesture, tone, and comment.

- You become the integrator, resolving tensions between teams that once sat comfortably outside your remit.

- You slow down your thinking, because leaders must rise above the swirl of daily operations to focus on longer-term direction.

- And you begin to see the world differently, recognising that your influence lies not in doing more, but in enabling others to thrive.

European leaders often speak about this with striking candour. Jean-Dominique Senard, Chairman of Renault, once explained that the most disorienting part of leadership was not the scale of responsibility, but the shift from having a narrow field of control to guiding an organisation through persuasion, coherence, and integrity.

Leadership, he said, is not an assertion of power, but an expression of stewardship.

Leaders who have made the leap

Many of Europe’s contemporary business leaders exemplify the transformation from manager to leader.

Ana Botín, Executive Chair of Santander, moved from leading country operations to reshaping one of Europe’s largest banking groups. She has spoken of how leadership required not only strategic renewal but cultural renewal—building a more innovative, open, and internationally connected bank.

Bjørn Gulden, who led Puma before becoming CEO of Adidas, made the leap from operational manager to brand builder, cultural architect, and enterprise leader. His tenure emphasised the importance of purpose, team dynamics, and long-term brand equity over short-term performance.

Carlo Messina, leader of Intesa Sanpaolo, transitioned from finance professional to enterprise strategist, balancing profitability with social programmes, regional development, and digital transformation—an example of leadership attuned to the broader societal role of European institutions.

Ilham Kadri, Emma Walmsley, Carsten Spohr, and Frans van Houten similarly show that leadership in modern European organisations is not merely about commercial success but about shaping long-term value, building trust, and steering complex enterprises with vision and humanity.

The courageous leap forward

Stepping from manager to leader is one of the most courageous transitions in professional life, not because the tasks become harder, but because the expectations become deeper. Leadership demands a broader view, a longer horizon, and a willingness to transcend the very expertise that once defined you.

To lead is to see the enterprise as an interconnected system, to create value that endures, to elevate the performance and potential of others, and to hold steady in uncertainty.

It requires humility, curiosity, courage, and a commitment to something larger than oneself.

The world today—volatile, interconnected, opportunity-rich, and uncertain—needs leaders who are equal parts strategist, architect, and steward. Leaders who embrace possibilities, unite people, build platforms for progress, and imagine futures that others cannot yet see.

The leap from manager to leader is not simply a step upward. It is a step forward—into a future that you have the opportunity, and the responsibility, to shape.

Explore more …

- Download the Global Business Trends Report 2026 by Peter Fisk.

- Download the Trend Kaleidoscope 2026 summarising all the latest trend reports.

And also …

- Download Megatrends 2035: the 6 dramatic forces shaking up every market by Peter Fisk.

- Download Breakthrough Ideas for Business Leaders: Reshuffle to Regenerate by Peter Fisk.

- Download Strategic Jazz: from Sting’s improvisation to strategy’s adaptiveness by Peter Fisk.

- Download The Dual OS of Business: how to create tomorrow and deliver today by Peter Fisk.

- Download The New Growth Playbook: Unlocking the growth engines of your future by Peter Fisk.

- Download The Super Innovators: 10 ways to disrupt conventions and reinvent futures by Peter Fisk

- Download The Courageous Leap: Stepping up from manager of today, to leader of the future by Peter Fisk.

More from the blog