Syzygy: The Secret Code of Business Transformation … markets are continually shifting and shaping, requiring business to be constantly reimagining and reinventing

September 9, 2024

Syzygy has its origins in the Greek word suzugia, meaning yoked or paired, and became popular in 18th century Latin and English. More generally is means a conjunction or alignment. Synergy is a more modern word derived from it.

What does it take to transform your business effectively?

Consider how these organisations have reinvented themselves:

- Berkshire Hathaway started as a merger of the Berkshire Spinning Association and Hathaway textile mill. Warren Buffett transformed it into an investment powerhouse.

- Domino’s Pizza stands out amongst today’s fast food retailers, reinventing itself to offer a digitally-centric brand experience that people will pay more for.

- National Geographical grew famous through print. Then it started exploring more instant and immersive media, becoming the most popular brand on Instagram.

- Nintendo was founded in 1889 by Fusajiro Yamauchi as a playing card company, transformed over the last 60 years his grandson Hiroshi into a digital gaming empire.

- Shell was a London shop specialising in exotic shells from Asia before becoming the world’s largest oil company, and now seek to transform itself into clean energy.

- Western Union, once a network of early telegraph companies in the American outback, reinvented itself as the world’s largest money transfer service.

- Wipro started in 1945 selling vegetable oil, before diversifying into other products. It is now one of the world’s largest IT outsourcers and software engineers.

- American Express’s Ken Chenault says, “successful transform demands unchanging change”, requiring constant values but relentless reinvention.

Business Transformation

Sometimes it’s a financial crisis, sometimes it’s the threat from a disruptive competitor, sometimes growth stagnates as markets mature or decline, sometimes it’s the opportunity to ride a new global megatrend, and sometimes it’s the result of proactive strategic planning.

To better understand the dynamics of why and how transformation happens, Innosight’s “Transformation 20” study evaluated the strategic change efforts of many companies, seeking to identify best practices across industries and geographies. The ranking is based on three factors: finding new growth (% of revenue beyond core), repositioning the core (giving the legacy business new life), financial growth (revenue, profit and economic value over the transformation).

Scott Anthony describes the essence of this kind of transformation: “What businesses are doing here is fundamentally changing in form or substance. A piece, if not the essence, of the old remains, but what emerges is clearly different in material ways. It is a liquid becoming a gas. Lead turning into gold. A caterpillar becoming a butterfly.”

Here are some examples of such transformations:

- Adobe … transformed from product to service, from document software into digital experiences, marketing, commerce platforms and analytics

- Amazon … transformed its own infrastructure into “Amazon Web Services” which enables other organisations to operate their online businesses.

- DBS … transformed itself from a regional bank to a global digital platform, a “27,000-person start-up” and crowned “Best Bank in the World.”

- Microsoft … transformed from a business model based primarily on selling product licenses (IP), to a cloud-based platform-as-a-service business.

- Netflix … shifted from DVDs by mail into the leading streaming video content service and now a top original content provider.

- Ping An … transformed itself from insurance into a cloud tech business providing fintech and AI-based medical imaging & diagnostics.

- Tencent … transformed from social and gaming business to a platform embracing entertainment, autonomous vehicle, cloud computing, and finance.

Transformation is about significant, lasting, non-reversible change to the way in which the company operates and creates value, typically where at least 25% of total revenues comes from new business units or business models. It can take time, 10 years as demonstrated by Orsted, but also sets the business on a new course for a better future.

Whilst digital technologies are a significant enabler of transformation, companies should beware of the term “digital transformation” which is often used to describe the automation of business functions, seeking more efficiency and speed, or broader applications of technology. Similarly, “culture change” is not the same as business transformation. In both cases it is only transformative if it is accompanying by a more holistic reinvention of the business, including its strategy and business models, propositions and performance.

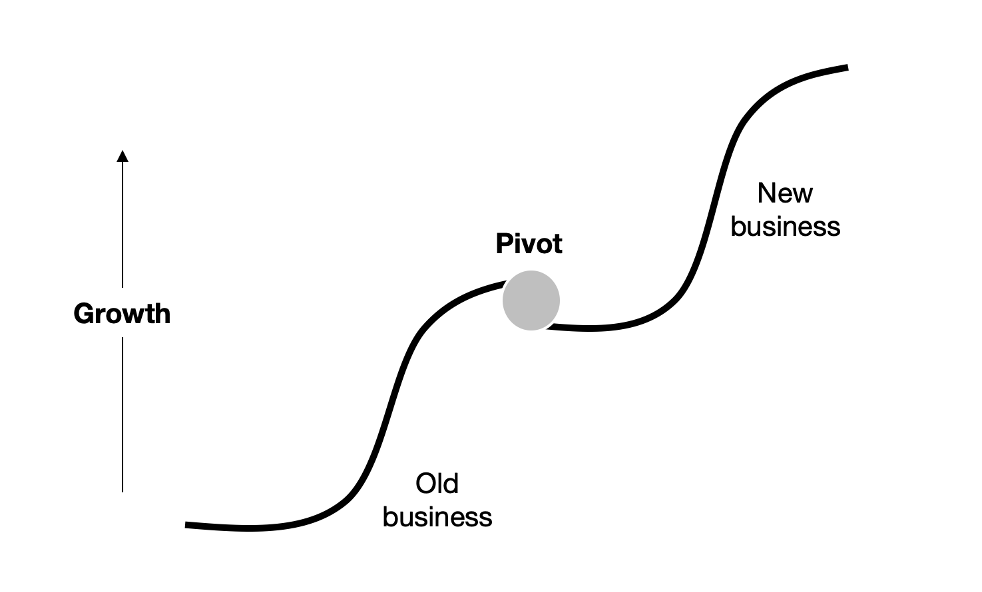

Pivot to a new space

The destination of any transformation might be quite different from how it was initially envisioned. Many projects, and even businesses, find that they reach a point where they need to significantly change direction, based on what they have learnt. This is a “pivot”, and has been a feature of many start-up journeys in recent years.

- Instagram initially known as Burbn started out as an online discussion forum developed by Kevin Systrom whilst learning how to program, but now has 1 billion users simply sharing images.

- Slack started as a game called Glitch, developed by Stewart Butterfield after he sold Flickr. The game didn’t take off, but its platform evolved to become Slack, a place for collaborative working.

- Twitter was previously known as Odeo, a podcasting platform before podcasts took off. Jack Dorsey decided to shift to microblogging as he called, it, rebranding it as Twitter, and a leader in short posts and status updates.

- YouTube originated as a dating site, encouraging people to upload videos of themselves. Few people embraced the concept, but when the site opened up to anyone who wanted to share a video, over 2 billion people signed up.

For larger organisation, they need to learn to pivot as part of their evolution, and as a sequence of transformations.

As they ride the “S curves” of market change, they accelerate as new ideas take off, but then slow as ideas mature. Eventually, without change, the old business declines, as the market moves in new directions, and a new S Curve takes off. The challenge of transformation is to ride the S Curves, jumping to the new curve whilst still thriving on the old curve, transforming before you need to.

Evolve to revolve

Transformation does not have to be a sudden shift from one state to another, and can be more evolutionary. Indeed a persistent, focused approach to incremental change, not simply on efficiency but on improved competitive performance, can sometimes have just as much transformational impact.

I first learnt about “marginal gains” whilst watching cycling. Dave Brailsford was the new performance director of Team GB, who in recent years have come to dominate the sport. Marginal gains was said to be his secret to superior performance.

Brailsford and his coaches began by making small adjustments you might expect from a professional cycling team. They redesigned the bike seats to make them more comfortable and rubbed alcohol on the tires for a better grip. They asked riders to wear electrically heated overshorts to maintain ideal muscle temperature while riding and used biofeedback sensors to monitor how each athlete responded to a particular workout. The team tested various fabrics in a wind tunnel and had their outdoor riders switch to indoor racing suits, which proved to be lighter and more aerodynamic.

Then they went further. They tested different types of massage gels to see which one led to the fastest muscle recovery. They hired a surgeon to teach each rider the best way to wash their hands to reduce the chances of catching a cold. They determined the type of pillow and mattress that led to the best night’s sleep for each rider. They even painted the inside of the team truck white, which helped them spot little bits of dust that would normally slip by unnoticed but could degrade the performance of the finely tuned bikes.

1% became the team mantra, and led to phenomenal success, including six Tour de France victories in seven years, and multiple Olympic gold medals. Whilst some have become concerned that the search for an edge can take sports to blurred ethical practices, Brailsford has always maintained that every gain was scientific and legal.

Indeed, in 2018, Brailsford was the technical mastermind behind Eliud Kipchoge’s first sub 2 hour marathon, focusing on every marginal gain from the surface and camber of the road, to the weather temperature and humidity, pace making and shoe design.

From cycling to marathon running, cyber security to car manufacturing, organisations have found that 1% improvement can make a big difference. Lots of small changes can add up to more than one big change. Concentrate on making many 1% improvements and you’ll find the compound effect is huge, without putting all your eggs in one basket of transformational change.

Exploit and Explore

I spent much of 1999 working with Philips. I remember it well, largely because of the regular short flight from London to Eindhoven. Even the earliest flight, often delayed by fog, meant that I rarely arrived at the head office before 1100 because of the time difference. In Holland, lunch is at 1130, and always a cheese roll and carton of milk. They grow tall on their dairy intake. As we ate, change was always the topic of conversation.

Philips was founded back in 1891 by Gerard Philips who bought an empty factory in Eindhoven, where the company started the production of carbon-filament lamps.

Over the next century the company started to extend into other electronics businesses such as vacuum tubes, electric shavers, radios (and even a radio station). Televisions followed, which evolved into a battle of formats for video cassettes and laser discs. Toothbrushes too. Throughout this time, the core lighting business had continued, evolving from filament bulbs into new formats such as LEDs, supported by its semiconductor business.

In the early 2000s, Philips symbolically shifted its head offices from Eindhoven to Amsterdam, and started to acquire a number of healthcare companies, from diagnostic scanners to surgical devices. It’s core started to shift away from electronics. In 2018 it formally divested its lighting business, which was renamed as Signify, although continuing to use the Philips brand on its products under license. Healthcare became the new core business.

Transform for today and tomorrow

How can you create the future, whilst at the same time deliver today?

Janus was a Roman god with two sets of eyes, one pair focused on what lay behind, the other on what lay ahead.

Change unlocks new opportunities to create new markets. It is the moment when a business typically needs to protect and improve its current activities, but also seize the opportunities of tomorrow, to explore and create new businesses.

Like Janus, business needs to be ambidextrous, to simultaneously think and work in the short and long-term. Short-term sales earn the cash, but also the permission, to create a better future. However, this is not a sequential challenge, nor a parallel challenge. The organisation shouldn’t delay tomorrow in order to win today or work separately on both.

The trick is to ensure that today leads to tomorrow, short-term actions lead to long-term progress. Too many leaders become obsessed by the short-term, and lose sight of the bigger goals. Of course, a heads-down focus on grinding out results looks good, often sub-servient to the perceived impatience of investment analysts. But this misses the point. Investors are most interested in future success, today is just a guide to it.

Dual Transformation

Scott Anthony, in his book “Dual Transformation”, describes this shift as three components.

- Transformation A: repositioning and improving the core business to maximise resilience (eg Adobe moving from packaged software to SaaS).

- Transformation B: creating a new growth engine (eg Amazon adding cloud computing services, and streaming content on top of ecommerce).

- Capabilities C: the best way to share assets and resources, brand and scale, and managing the interface between the core and the new.

Transformation A involves accepting changed circumstances, devising new metrics, and bringing in fresh talent experienced in emerging work environments. Transformation B requires understanding of future opportunities, changing consumers, and value patterns. This helps develop new business models through iterative experimentation and willingness to pivot. This may involve acquiring other companies and forging new partnerships, depending on expectations of impact periods.

Anthony likens the capability link to an airlock in a spaceship or submarine. This team includes savvy veterans and diplomatic managers, but the business leader will need to drive hard decisions on which core skills are relevant during transformation, and arbitrate during the inevitable arguments and turf wars. Tough calls will need to be made regarding speed of operation, pricing options, and assessing some of the inevitable failures along the way. Other challenges in dual transformation are balancing attention and assets, and protecting traditional income streams while also growing new sources in a slow and experimental manner.

Shifting the core

As businesses evolve, their centre of gravity moves.

We see this in the evolution of IBM, which grew famous as the innovator of mainframe computers. As the market shifted, driven by technological evolution, from mainframe to desktop to laptop, IBM found many more competitors.

For some time it moved with the trend, developing its own desk and laptops, whilst also exploring new business areas, particularly in services like consulting. Eventually it recognised that its strength was no longer in making any type of computers, but in the advice it could offer, and shifted to become a consulting business at its core.

The shit in the core can be seen in three stages:

- Focus on the core: clearly define your core business, strengthen it and seek to drive growth through it in existing and new markets

- Beyond the core: extend into adjacent markets, that can leverage off the core like IBM into services, with their own revenue streams

- Redefine the core: as markets evolve, the old core business may start to decline, before which is the time to shift to consolidate the new core

Whilst this shift might seem a fundamental transformation of the business, as we saw with Philips, it might simply be about following the same purpose, but interpreting how to deliver on that purpose in new and evolving ways. The shift might equally be represented by a more intangible asset, such as brand or capability, which can be deployed with partners in new industries, as in the shift of Ping An.

Outside in, Inside out

DBS is regarded by many as the world’s most innovative bank. The Singapore-based bank seeks to deliver a new kind of banking experience that is so simple, seamless and invisible, that customers have more time to spend on the things they care about.

CEO Piyush Gupta calls it “the invisible bank” where financial transactions are embedded deep within the activities of everyday life – from travel to shopping, eating to entertainment. No longer do people need to think of banking as a separate activity, it is part of everything.

Whilst much of DBS’ transformation from a very average regional bank to become a global leader, has been about digital technologies, Gupta says that it is not about the technology.

“If we just tried to apply technology to the existing banking model, we would just end up being an efficient bank” he says, which he sees as ok, but not exactly ambitious. What he really wanted to do was transform the concept of banking so that it can make people’s lives better.

Every child in Singapore, for example, now wears a DBS fitness bank, which is supplied free of charge by schools. The device enables kids to gamify their fitness, comparing how many steps they have made each day, to improve health. However it also has a GPS whereabouts app, so parents know where their kids are, for safety. And an electronic payment app for school travel and meals.

To achieve this transformation, Gupta realised that he had to create a customer-centric business first, before he could digitalise it. This required a fundamental change in culture and processes, products and services, Over three years he worked tirelessly to get people to see what they did from a customer perspective, using high energy “hackathons” in the business, to engage people and generate new ideas.

Only when he was satisfied that the business had a new mindset, and had at least started on a transformation to true customer-centricity, did he begin to explore the potential of new technologies to facilitate and accelerate the transformation.

“This is not putting customers at the centre of banking” he says “but about embedding banking into people’s everyday lives”.

Outside in

In my book “Customer Genius” I describe the transformational journey to become a customer-centric business. From a vision about making life better to deep insights about what matters most to your customers, through problem solving and value propositions, customer experiences and relationships, I defined a business built around people not around products.

Transforming your business from the outside in starts with:

- Customers: who do you want to serve, why and how?

- Insight: what do they really want, and what matters most?

- Experience: how to develop solutions to deliver the benefits?

- Engagement: why they will be attracted to the proposition?

- Delivery: how to deliver it, in a distinctive, profitable way?

Customer-centric businesses thrive on a passion for service, to “go the extra mile” for their customers, to build retention and loyalty as a more certain future streams of profits. It is a simple, human, motivating way to think about why you are in business.

Most companies have been trying to develop a “customer-centric” culture for at least 25 years. Being in tune with the customer enables companies to be more responsive to markets, to retain customers through better service, to differentiate from competitors, but also be more aligned with the changing outside world.

Inside Out

But then I hit an ideological barrier. An alternative perspective is that business should change from the “inside out”. Shouldn’t you start with the values and virtues of your organisation, and then make them strong and attractive? “Steve Jobs never asked customers what they wanted, and customers don’t really know anyway” they would say. Or to quote Richard Branson “employees come first, customers come second”.

Transforming your business from the inside out starts with:

- People: what do we do, what are we motivated by?

- Capability: what are our skills, our distinctive strengths?

- Products: which products to develop, quality and cost?

- Process: how to deliver it in a fast and efficient way?

- Sales: how many can we sell, to ensure our profitability?

There is logic in this approach too. Whilst the old adage that a business should “focus on your core competences” is outdated – maybe true in a steady state world, but not one of relentless changing opportunities and partnerships – the real strength of thinking inside out is to build on your culture. If organisations are defined by people, then cultures, and the beliefs and behaviours which they drive, are sources of strength and differentiation.

You could say that this is semantics, but for many leaders it can be confusing. “Inside out” is guided by doing what you do better, the more efficient use of resources and new applications of capabilities. “Outside in” is driven by doing what customers want, innovation and agility in response to change.

I remember this “outside in vs. inside out” debate as I discussed growth strategy with an executive team of a Silicon Valley company. They were a technology company, in fact almost every person was a trained software engineer. To them the most important document was the “product roadmap”. This guided their progress through subsequent releases of products, as their products got better – in their case, faster, smaller, cheaper.

I questioned whether this is what customers really wanted. Shouldn’t we be guided by what matters most to customers, and when they want it, and how we can enhance the product through additional products, services, and experiences? Yes maybe. But the product, to them was the king. It took at least 18 months of culture change before I eventually got them to begrudgingly respect the “customer roadmap.”

Transforming with purpose

The answer, as in the story of DBS’s transformation, is that you need both of course. The best starting actually is neither outside or inside, but with your purpose. Why do you exist? What is the contribution which you seek to make to the world, to society, to people?

A purpose is ultimately an “outside in” statement. It is based on what you enable people to do, rather than what you do. However a purpose is “inside out” in the sense that it becomes the guiding principle of the whole business, its culture, its strategic choices, and motivation for why we come to work each morning.

Transformation goes beyond what do customers want, or what capabilities do we have. It needs to start at a higher level. You might not currently have the right customers, or even be in the right market. As Steve Jobs said, they might not be able to articulate what they want, although I suggest he was actually bringing a customer mindset into play for them.

In a world where you can do anything, be guided by your purpose. Create a business that succeeds by doing more for the world, bringing together the inspiration of the outside, and imagination of the inside.

More from the blog