Accelerating decarbonisation … the race to net zero will not be won through reduction alone … but through an inspired approach to sustainable innovation and business transformation

February 22, 2024

Green cement, upcycled fashion, clean energy, plant-based food, electric vehicles … the challenge of decarbonisation is the catalyst to innovate solutions, and reinvent organisations.

Across industries and geographies, the urgency to achieve “net zero” is dominating corporate strategies, as we as sustainability agendas. It has become a key factor in driving competitive advantage (customers choosing suppliers who can help them reduce their own emissions), as well as employee engagement, investor perceptions, government and social goodwill, and ultimately value creation.

Sustainable businesses do better – overall they typically outperform average performers by 42% in market value. But they also attract the best talent, customers are likely to pay a premium of 10-25% depending on sector, investors take a more positive view of future potential, and government and social support are much greater.

While the focus is on carbon emissions, there is much more to achieving success:

- Sustainably Better is much more than ESG, as strategies are much than metrics, and environmental issues are just part of the story. Environmental protection, social improvement and economic growth need to work together. Otherwise the emerging economies will never support it, and generally we will have unsustainable compromise rather than sustainable growth, value creation and a better future.

- Net Positive rather than just net zero, because ultimately an organisation exists to make a contribution, to make some net positive benefit to the world. And in many cases the best strategies combine reduced environmental impacts, with positive social impacts. Or indeed, the environmental impacts could be positive too through closed loop solutions, replenishing resources, and regenerating the planet, and local environments, to better than before.

- Sustainable Innovation is the real key to solving the problem, or more precisely sustainable innovation – using the problem, for example, carbon emissions, as the catalyst to create something better, cheaper, faster. There is no coincidence that electric vehicles tend to be the most stylish, and increasingly highest performing, too. New technologies will play a dramatic, exponential role in unlocking this innovativeness.

- Business Transformation is required to address these challenges and opportunities. Circular, net positive, organisations are only achievable with the support of new business models, new organisation processes and new market structures of today. Transformation is the leadership superpower of the 21st century, but it is complex, and takes time. It needs clarity of vision, discipline in delivery, and persistence to realise its full value.

Which are the critical industries for decarbonisation?

- Energy: Over the past decade, the costs of renewables have dropped substantially—solar power by as much as 80% and wind power by about 40% —making them economically competitive with conventional fuels, such as coal and natural gas. A successful transition to net zero will require meeting increased demand for electricity by scaling up renewable, low-carbon power generation and building enough flexibility in power systems to match supply and demand.

- Cars and Planes: Sales and planned production of low-emissions cars have surged. By 2035, we project that new passenger-vehicle sales in the largest automotive markets (China, EU, and USA) will be close to 100 percent electric. To make low-emissions vehicles the new norm, new supply chains and manufacturing capabilities are needed, as well as corresponding infrastructure, such as charging stations and hydrogen fuelling stations.

- Cement and Steel: Some cement companies have used advanced analytics and other operational tactics to optimise for energy efficiency, while others have experimented with emissions-reducing production methods. A circular model starts with existing materials, creating new buildings from old waste. Going forward, the industry could explore alternative energy sources (such as biomass), carbon capture, and digitisation of manufacturing.

- Agriculture and Food: Promising technologies in animal feeding, soil carbon sequestration, and crop fertilisation are in development or are already in use. The market for cultivated meats—those grown in bioreactors from animal cells—could become a $25 billion global industry by 2030. Uptake of zero-emissions farm equipment and machinery—including tractors, harvesters, and dryers—is behind that of electric vehicles, but cost reductions and supportive financing could accelerate adoption.

What does the Paris Agreement demand?

The UN Climate Change “Paris Agreement” is a shared commitment by 196 nations at COP21, head in Paris in 2015. It sets the stage for global climate action, emphasizing the urgency of reducing emissions and transitioning toward a sustainable, low-carbon future. Key points are:

- Limiting global warming by holding “the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels” and pursuing efforts to limit it to 1.5°C above, which is the point beyond which significant climate impacts are caused, including droughts, heatwaves, and extreme rainfall.

- Reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 43% by 2030, after a projected peak in 2025, to achieve the 1.5°C goal, with each country developing their own Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) defining their actions to reduce emissions and build resilience to climate change.

- Achieving net-zero emissions by 2050, where “net zero” means balancing emissions by absorbing an equivalent amount from the atmosphere. The agreement recognises that this is a shared commitment, and will require cooperation between nations to achieve it, sharing knowledge and practices, and collaboration on new the transformations required.

That’s the absolute minimum, to retain our world as we know it, which is the focus of politicians and environmentalists. But as business we need to achieve much more. Delivering the Paris Agreement in a way that also creates a better business, with a more prosperous future – which is why sustainably better, net positive, sustainable innovation and business transformation, are key.

So what are the practical strategies?

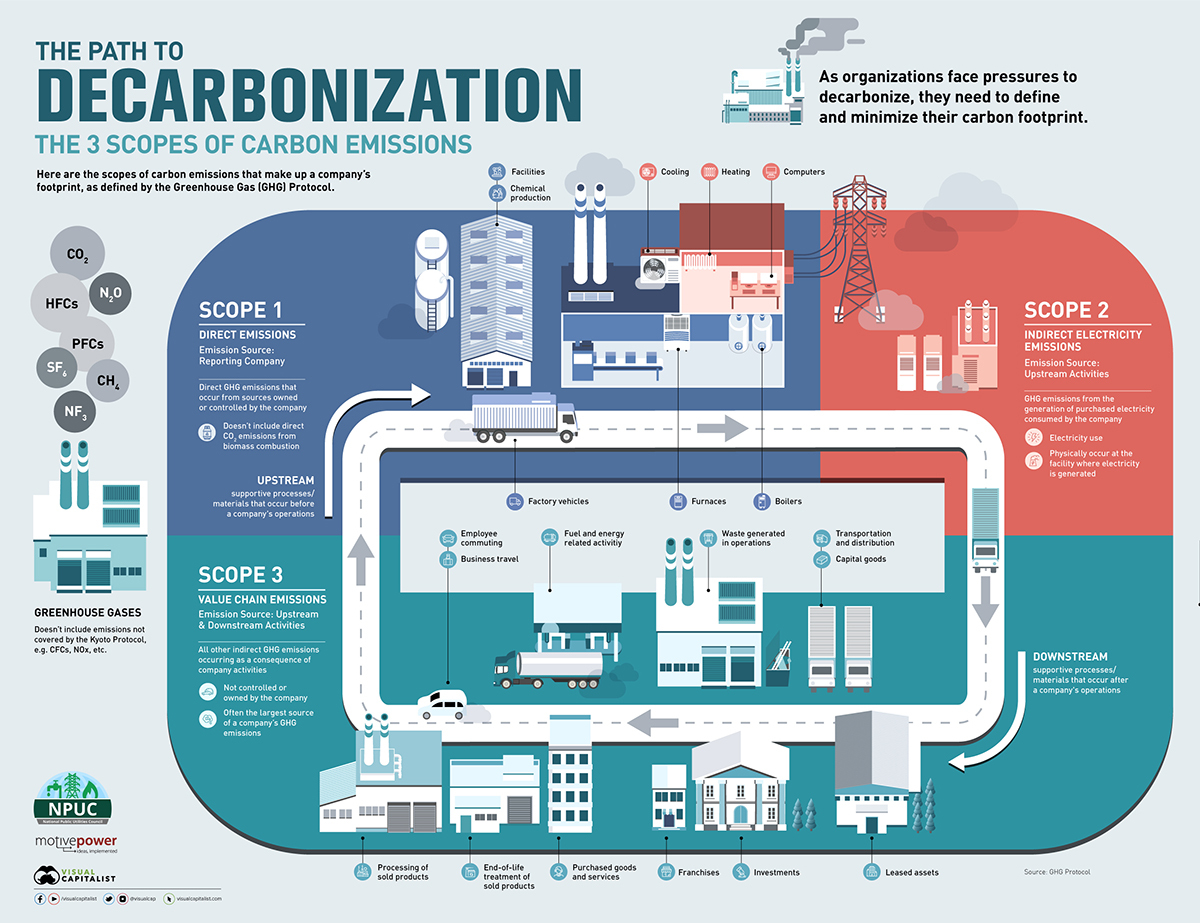

The most commonly used breakdown of a company’s carbon emissions are the three scopes defined by the Greenhouse Gas Protocol, a partnership between the World Resources Institute and World Business Council for Sustainable Development.

The GHG Protocol separates carbon emissions into three buckets: emissions caused directly by the company, emissions caused by the company’s consumption of electricity, and emissions caused by activities in a company’s value chain.

- Scope 1: Direct emissions: these emissions are direct GHG emissions that occur from sources owned or controlled by the company, and are generally the easiest to track and change. Scope 1 emissions include factories, offices, vehicles, production.

- Scope 2: Indirect electricity emissions: These emissions are indirect GHG emissions from the generation of purchased electricity consumed by the company, which requires tracking both your company’s energy consumption and the relevant electrical output type and emissions from the supplying utility. They include electricity use (e.g. lights, computers, machinery, heating, steam, cooling) and emissions occur at the facility where electricity is generated.

- Scope 3: Value chain emissions: These emissions include all other indirect GHG emissions occurring as a consequence of a company’s activities both upstream and downstream. They aren’t controlled or owned by the company, and many reporting bodies consider them optional to track, but they are often the largest source of a company’s carbon footprint and can be impacted in many different ways. This include supplies, investments, employee travel, company waste.

Most uses of the GHG Protocol by companies includes many of the most common and impactful greenhouse gases that were covered by the UN’s 1997 Kyoto Protocol. These include carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide, as well as other gases and carbon-based compounds.But the standard doesn’t include other emissions that either act as minor greenhouse gases or are harmful to other aspects of life, such as general pollutants or ozone depletion.

There are many different types of carbon emissions for companies (and governments) to consider, measure, and reduce on the path to decarbonisation. But that means there are also many places to start.

Practical examples

Cities are a major arena in the race to net zero. They consume over two-thirds of global energy resources and account for more than 70% of CO2 emissions worldwide.1More than half (56%) of the global population currently lives in an urban area. The UN expects that number to reach 68% by 2050.

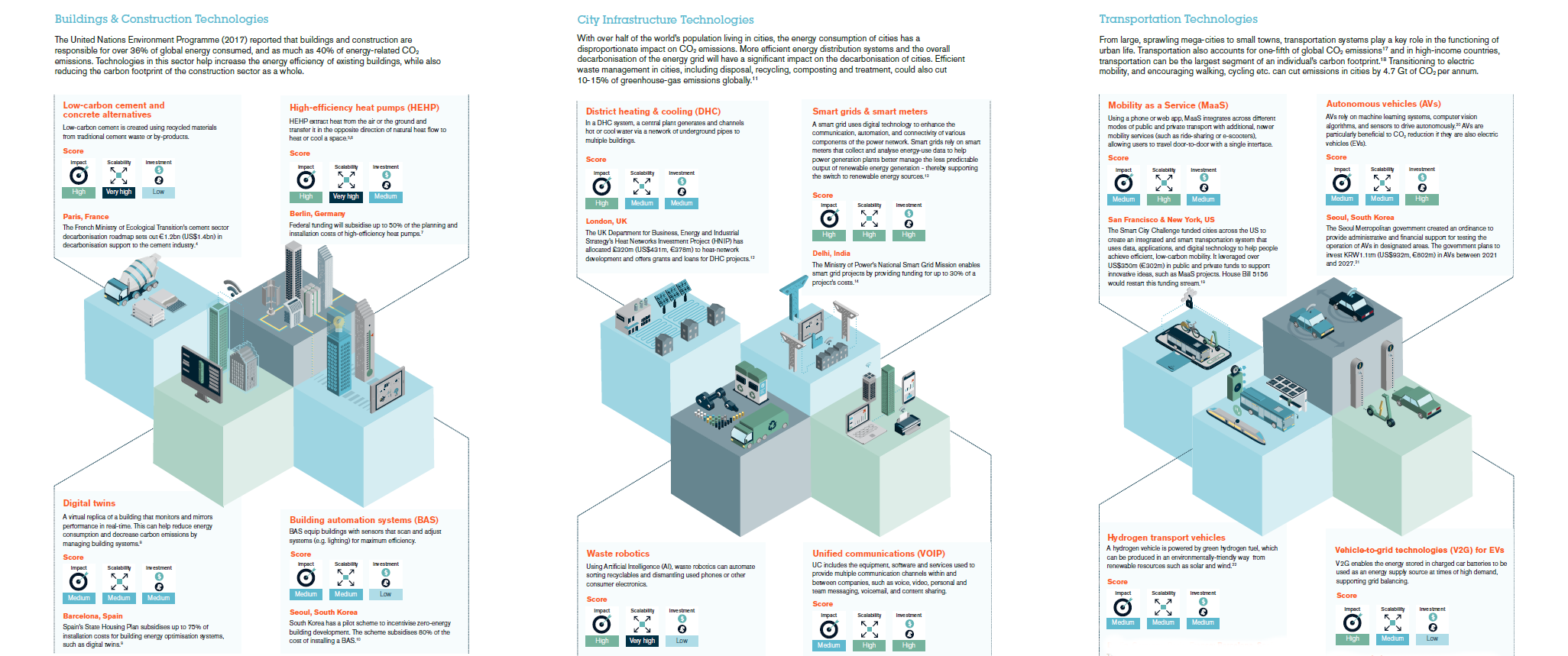

New research by Economist Impact, supported by Osborne Clarke, identifies some of the technologies that can help cities achieve their carbon-emission targets while also creating jobs, lowering energy costs for residents, and improving overall quality of life. It considers three categories of technologies – support building, infrastructure and mobility.

The UN Environment Programme (2017) reported that buildings and construction are responsible for over 36% of global energy consumed, and as much as 40% of energy-related CO2 emissions. Technologies in this sector help increase the energy efficiency of existing buildings, while also reducing the carbon footprint of the construction sector as a whole.

The energy consumption of cities has a disproportionate impact on CO2 emissions. More efficient energy distribution systems and the overall decarbonisation of the energy grid will have a significant impact on the decarbonisation of cities. Efficient waste management in cities, including disposal, recycling, composting and treatment, could also cut 10-15% of greenhouse-gas emissions globally.

From large, sprawling mega-cities to small towns, transportation systems play a key role in the functioning of urban life. Transportation also accounts for one-fifth of global CO2 emissions17 and in high-income countries, transportation can be the largest segment of an individual’s carbon footprint.18 Transitioning to electric mobility, and encouraging walking, cycling etc. can cut emissions in cities by 4.7 Gt of CO2 per annum.

More from the blog